49 Reading: The Organizational Approach to Ethics

The Organizational Approach to Ethics

Ethics is more than a matter of individual behavior; it’s also about organizational behavior. Employees’ actions aren’t based solely on personal values alone: They’re influenced by other members of the organization, from top managers and supervisors to coworkers and subordinates. So how can ethical companies be created and sustained? In this section, we’ll examine some of the most reasonable answers to this question.

How to Create and Sustain Ethical Companies

As an Employee

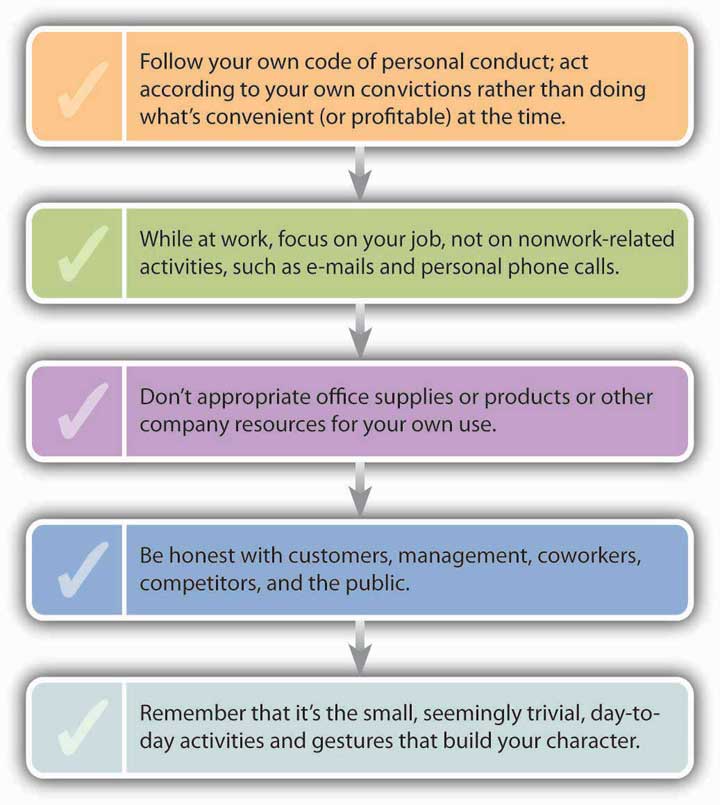

How, as an employee, can you maintain an ethical position? A few rules of thumb can guide you. We’ve summed them up in Figure 1, “How to Maintain Honesty and Integrity,” below:

Whistle-Blowing

As we’ve seen, the misdeeds of Betty Vinson and her accomplices at WorldCom didn’t go undetected. They caught the eye of Cynthia Cooper, the company’s director of internal auditing. Cooper, of course, could have looked the other way, but instead she summoned the courage to be a whistle-blower—an individual who exposes illegal or unethical behavior in an organization. Like Vinson, Cooper had majored in accounting at Mississippi State and was a hard-working, dedicated employee. Unlike Vinson, however, she refused to be bullied by her boss, CFO Scott Sullivan. In fact, she had tried to tell not only Sullivan but also auditors from the huge Arthur Andersen accounting firm that there was a problem with WorldCom’s books. The auditors dismissed her warnings, and when Sullivan angrily told her to drop the matter, she started cleaning out her office. But she didn’t relent. She and her team worked late each night, conducting an extensive, secret investigation. Two months later, Cooper had evidence to take to Sullivan, who told her once again to back off. Again, however, she stood up to him, and though she regretted the consequences for her WorldCom coworkers, she reported the scheme to the company’s board of directors. Within days, Sullivan was fired and the largest accounting fraud in history became public.

As a result of Cooper’s actions, executives came clean about the company’s financial situation. The conspiracy of fraud was brought to an end, and though public disclosure of WorldCom’s problems resulted in massive stock-price declines and employee layoffs, investor and employee losses would have been greater without Cooper’s intervention. Even though Cooper did the right thing, the experience wasn’t exactly gratifying. A lot of people applauded her action, but many coworkers shunned her; some even blamed her for the company’s troubles. She’s never been thanked by any senior executive at WorldCom.

Refusing to Rationalize

Despite all the good arguments in favor of doing the right thing, why do many reasonable people act unethically (at least at times)? Why do good people make bad choices? According to one study, there are four common rationalizations for justifying misconduct[1]

- My behavior isn’t really illegal or immoral. Rationalizers try to convince themselves that an action is OK if it isn’t downright illegal or blatantly immoral. They tend to operate in a gray area where there’s no clear evidence that the action is wrong.

- My action is in everyone’s best interests. Some rationalizers tell themselves: “I know I lied to make the deal, but it’ll bring in a lot of business and pay a lot of bills.” They convince themselves that they’re expected to act in a certain way, forgetting the classic parental parable about jumping off a cliff just because your friends are[2]

- No one will find out what I’ve done. Here, the self-questioning comes down to “If I didn’t get caught, did I really do it?” The answer is yes. There’s a simple way to avoid succumbing to this rationalization: Always act as if you’re being watched.

- The company will condone my action and protect me. This justification rests on a fallacy. Betty Vinson may honestly have believed that her actions were for the good of the company and that her boss would, therefore, accept full responsibility (as he promised). When she went to jail, however, she went on her own.

Here’s another rule of thumb: If you find yourself having to rationalize a decision, it’s probably a bad one. Over time, you’ll develop and hone your ethical decision-making skills.

So, how do organizations establish a culture of ethics from the “top down”?

Ethical Leadership

Organizations have unique cultures—ways of doing things that evolve through shared values and beliefs. An organization’s culture is strongly influenced by senior executives, who tell members of the organization what’s considered acceptable behavior and what happens if it’s violated. In theory, the tone set at the top of the organization promotes ethical behavior, but sometimes (as at Enron) it doesn’t.

Before its sudden demise, Enron fostered a growth-at-any-cost culture that was defined by the company’s top executives. Said one employee, “It was all about taking profits now and worrying about the details later. The Enron system was just ripe for corruption.” Coupled with the relentless pressure to generate revenue—or at least to look as if you were generating it—was a climate that discouraged employees from questioning the means by which they were supposed to do it. There may have been chances for people to speak up, but no one did. “I don’t think anyone started out with a plan to defraud the company,” reflects another ex-employee. “Everything at Enron seemed to start out right, but somewhere something slipped. People’s mentality switched from focusing on the future good of the company to ‘let’s just do it today.'”[3]

Exercising Ethical Leadership

Leaders should keep in constant touch with subordinates about ethical policies and expectations. They should be available to help employees identify and solve ethical problems, and should encourage them to come forward with concerns. They’re responsible for minimizing opportunities for wrongdoing and for exerting the controls needed to enforce company policies. They should also think of themselves as role models. Subordinates look to their supervisors to communicate policies and practices regarding ethical behavior, and as a rule, actions speak more loudly than words: If managers behave ethically, subordinates will probably do the same.

This is exactly the message that senior management at Martin Marietta (now a part of Lockheed Martin) sent to members of their organization. A leading producer of construction components, the company at the time was engaged in a tough competitive battle over a major contract. Because both Martin Marietta and its main competitor were qualified to do the work, the job would go to the lower bid. A few days before bids were due, a package arrived at Martin Marietta containing a copy of the competitor’s bid sheet (probably from a disgruntled employee trying to sabotage his or her employer’s efforts). The bid price was lower than Martin Marietta’s. In a display of ethical backbone, executives immediately turned the envelope over to the government and informed the competitor. No, they didn’t change their own bid in the meantime, and, no, they didn’t get the job. All they got was an opportunity to send a clear message to the entire organization.[4]

By the same token, leaders must be willing to hold subordinates accountable for their conduct and to take appropriate action. The response to unethical behavior should be prompt and decisive. One CEO of a large company discovered that some of his employees were “Dumpster diving” in the trash outside a competitor’s offices (which is to say, they were sifting around for information that would give them a competitive advantage). The manager running the espionage operation was a personal friend of the CEO’s, but he was immediately fired, as were his “operatives.” The CEO then informed his competitor about the venture and returned all the materials that had been gathered. Like the top managers at Martin Marietta, this executive sent a clear message to people in his organization: namely, that deviations from accepted behavior would not be tolerated.[5]

It’s always possible to send the wrong message. In August 2004, newspapers around the country carried a wire-service story titled “Convicted CEO Getting $2.5 Million Salary While He Serves Time.” Interested readers found that the board of directors of Fog Cutter Capital Group had agreed to pay CEO Andrew Wiederhorn (and give him a bonus) while he served an eighteen-month federal-prison term for bribery, filing false tax returns, and financially ruining his previous employer (from which he’d also borrowed $160 million). According to the board, they couldn’t afford to lose a man of Wiederhorn’s ability. The entire episode ended up on TheStreet.com’s list of “The Five Dumbest Things on Wall Street This Week.”[6]

Tightening the Rules

In response to the recent barrage of corporate scandals, more large companies have taken additional steps to encourage employees to behave according to specific standards and to report wrongdoing. Even companies with excellent reputations for integrity have stepped up their efforts.

Codes of Conduct

Like many firms, Hershey Foods now has a formal code of conduct: a document describing the principles and guidelines that all employees must follow in the course of all job-related activities. It’s available on the company intranet and in printed form and, to be sure that everyone understands it, the company offers a training program. The Hershey code covers such topics as the use of corporate funds and resources, conflict of interest, and the protection of proprietary information. It explains how the code will be enforced, emphasizing that violations won’t be tolerated. It encourages employees to report wrongdoing and provides instructions on reporting violations (which are displayed on posters and printed on wallet-size cards). Reports can be made though a Concern Line, by e-mail, or by regular mail; they can be anonymous; and retaliation is also a serious violation of company policy.[7]

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- At some point in your career, you might become aware of wrongdoing on the part of others and will have to decide whether to report the incident and become a whistle-blower—an individual who exposes illegal or unethical behavior in an organization.

- Despite all the good arguments in favor of doing the right thing, some businesspeople still act unethically (at least at times). Sometimes they use one of the following rationalizations to justify their conduct:

- The behavior isn’t really illegal or immoral.

- The action is in everyone’s best interests.

- No one will find out what I’ve done.

- The company will condone my action and protect me.

- Ethics is more than a matter of individual behavior; it’s also about organizational behavior. Employees’ actions aren’t based solely on personal values; they’re also influenced by other members of the organization.

- Organizations have unique cultures—ways of doing things that evolve through shared values and beliefs.

- An organization’s culture is strongly influenced by top managers, who are responsible for letting members of the organization know what’s considered acceptable behavior and what happens if it’s violated.

- Subordinates look to their supervisors as role models of ethical behavior. If managers act ethically, subordinates will probably do the same.

- Those in positions of leadership should hold subordinates accountable for their conduct and take appropriate action.

- Many organizations have a formal code of conduct that describes the principles and guidelines that all members must follow in the course of job-related activities.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in this section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

- Saul W. Gellerman, "Why 'Good' Managers Make Bad Ethical Choices," Harvard Business Review on Corporate Ethics, Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003, p 59. ↵

- Adrian Gostick and Dana Telford, The Integrity Advantage, Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2003, p 12. ↵

- See especially Tom Fowler, "The Pride and the Fall of Enron," Houston Chronicle, October 20, 2002, accessed April 24, 2006. ↵

- Episode recounted by Norm Augustine, "Business Ethics in the 21st Century," speech, Ethics Resource Center, accessed April 24, 2006. ↵

- Norm Augustine, "Business Ethics in the 21st Century," speech, Ethics Resource Center, accessed April 24, 2006. ↵

- William McCall, "CEO Will Get Salary, Bonus in Prison," CorpWatch, accessed April 24, 2006. ↵

- Hershey Foods, "Code of Ethical Business Conduct," accessed January 22, 2012. ↵