9 Corporate Crimes

Over the last century, workers in the United States have come to enjoy an expanding array of workplace protections. The minimum wage has continued to increase, albeit sporadically, and several state and city regulations now outpace stagnant federal protections. Workplace safety standards cover more workers than ever, and our modern ability to track occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities has helped to inform crucial policy change. Owing to the long struggles waged by civil rights and feminist leaders, employers can no longer fire workers solely on the basis of their race, gender, or religious preference without running the risk of the government holding them accountable. Organized labor has enormous influence in progressive political circles, and key union victories have gone a long way to change industry standards. In short, the fruits of decades of labor organizing are undeniable.

The government apparatus that has sprung up to enforce these protections is also impressive. The Department of Labor enforces 180 federal laws covering 10 million employers and 125 million workers (US Department of Labor 2015a). One of President Barack Obama’s goals was to grow the agency by more than 4 percent (Miller and Dinan 2015). Moreover, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s strategic plan has yielded some of the highest settlements in history, with the largest verdict to date in 2013 awarding $240 million to thirty-two men in the meat processing industry who suffered horrific discrimination and abuse at the hands of their employer (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2013). As these and other examples demonstrate, workers have made significant strides.

And yet, despite the proliferation of protections, expanding enforcement bureaucracies, and high-profile victories, there has nonetheless been a “rise in polarized and precarious employment systems” over the last four decades (Kalleberg 2011). These so-called “bad jobs,” Arne L. Kalleberg argues, are characterized by poor job quality in both economic and non-economic terms, including pay, benefits, and worker power (9–10). Many of these bad jobs have little effective government oversight (Bernhardt et al. 2008), are rarely unionized, have unpredictable schedules, and offer little upward mobility. These characteristics encompass what Marc Doussard (2013) refers to as “degraded work,” an employment trend fueled in large part by small and local businesses who are fighting to compete in tough economic environments. “Degraded” workers become disposable bodies as well as indispensable assets that allow companies to compete in the global economy (Uchitelle 2007). The precarious position of US workers is also tied inextricably to the even more egregious disposability of workers across the world, who stand waiting in the wings as industries relocate to find the cheapest and least protected labor source in a race to the bottom (Bales 2012).

Several categories of these “marginal workers” (Garcia 2012a), to use another term for them (for example undocumented immigrants, women, and racial and sexual minorities), face particular challenges in realizing their rights under US labor and employment law. Undocumented workers have limited remedies for injustices under the law and live under the constant threat of deportation. Women not only experience a higher incidence of pay inequity, discrimination, and sexual harassment but also shoulder a substantial burden of reproductive labor responsibilities that impact—and are impacted by—their work lives. Underrepresented racial minorities, including some immigrants, have poorer economic outcomes, are more likely to be in unprotected job categories, and face distinct challenges during the workplace grievance claims process. LGBT workers also continue to lack complete federal protection against discrimination at work. Each of these populations is subject to discriminatory practices that are the result of long-standing institutional inequalities.

Previous studies have examined this widespread workplace inequality, but they have tended to focus on what goes wrong at work or on why aggrieved workers never come forward. This emphasis reflects the undeniable reality that few workers actually manage to claw their way up what William L. F. Felstiner, Richard L. Abel, and Austin Sarat (1980) call the dispute pyramid: the three-part process of “naming, blaming, and claiming.” And when social scientists do look at the cases where workers engage in a sustained fight, we tend to highlight the valiant efforts of collective worker mobilizations or dramatic individual litigation sagas. However, the vast majority of employment laws offer worker protections through mundane administrative bureaucracies. This machinery predictably receives less attention, in part because it is less rousing, though no less important, than the chants coming from picket lines or the pleas of eloquent attorneys.

Although the vast majority of workplace violations never materialize into a formal claim, this book offers a unique perspective on the experiences of the choice few who do come forward. Their stories provide insight into power relations at the workplace and within the rights bureaucracies intended to regulate them. I pose a series of questions in this study from the outset: What propels a worker to come forward and file a claim, given all we know about the barriers to claims-making? What is the role of social networks in educating workers about their rights? How do they learn lessons about when to come forward, how far to push, and when to back down? I then examine the bureaucracies of labor standards enforcement from the perspective of workers on the ground. When does the system work for these courageous claimants? And, alternatively, why, even in the best of circumstances, do workers sometimes lose out in spite of the law’s good intentions?

This book is not an ethnography of the system from the perspective of the key actors who run it. Unlike numerous other scholars, I don’t interrogate the decisions that judges, bureaucrats, and attorneys make to adjudicate cases. I don’t cull data from hours of administrative hearings (though I did spend time in several such sessions), nor are my claims based on interviews with those stakeholders and experts who shape the claims-making process. There are, to be sure, many works covering these important perspectives (see for example Cooper and Fisk [2005], Cummings [2012], and Epp [2010], to name a few). Rather, this is a story, told from the perspectives of individual workers themselves, about how they experience the journey to justice: their plodding path through multiple agencies, appointments, medical visits, and reams of paperwork. Rather than asking how and why the labor standards bureaucracy operates as it does, I focus on how workers navigate its seas. What makes them decide to see their journey through, or, conversely, abandon ship?

PRECARITY AND POWER IN A GLOBAL ECONOMY

We live in a new global economy marked by innovation, ever-evolving technologies, and exponential concentrations of wealth accumulation. Global firms such as Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have become the household names that GM and Chrysler once were. Yet apart from the multiplying tech campuses and the explosion of high-end real estate, this new economy has also given rise to a low-wage workforce producing the goods and services that we have all come to expect—indeed, demand—cheaply and quickly. Industries such as construction, domestic work, food service, and retail are the pillars of the postindustrial societies; pay is low, conditions are often dangerous, and workplace violations run rampant. Therefore, while low-wage workers enjoy some of the most expansive formal rights in history, they also toil in a state of extreme precarity.

This is not to say that precarity is a novel phenomenon. Historically, the basic concessions of food stamps and cash assistance, and the promise of a modest income and access to health care in old age, were beyond the scope of imagination in the United States (Cohen 1991). There were important developments, most notably with the dawn of equal opportunity legislation during the civil rights and feminist movements. But these new laws did not, and could not, single-handedly erase centuries of racial and gendered subjugation of precarious workers (Lucas 2008).

While hailed as a unique marker of the modern economy, globalization—including the export of capital and the import of goods and labor—has cast a long historical shadow. For centuries, migrant workers have crossed oceans to reach the United States and elsewhere only to earn pitiful wages and endure conditions that are akin to, and in some cases are actually, indentured servitude. The informal economy, including what we refer to now as day labor, was once even more widespread than it is today, a means of economic survival for workers (both immigrant and native-born) as well as their employers (Higbie 2003; Valenzuela 2003).

The modern era also does not have a monopoly on exclusionary immigration policies rooted in racial and class-based xenophobia. Long before the emergence of post-9/11 nativism, the early twentieth century ushered in racist immigration rubrics. Former leader of the Knights of Labor Terence Powderly served as the first US commissioner general of immigration from 1898 to 1902. Despite the relatively progressive agenda of the Knights of Labor, his vision was squarely on the path of exclusion. Later, some of this early labor organization’s most revered leaders, such as Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor from 1886 to 1924, also became champions of Asian exclusion and other restrictionist policies (E. Lee 2003). The Immigration Act of 1965, which proponents initially thought would increase predominantly European migration, horrified many labor leaders as Latinos and Asians came streaming in. Furthermore, labor advocates stridently opposed guest worker programs and would later support employer sanctions under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (Fine and Tichenor 2012).

Has nothing changed, then, after more than a century of such exclusionary sentiments and weak to nonexistent workplace protections? To be sure, we are decades removed from a time when there was no minimum wage or occupational safety and health standards, and when workers lacked any formal right to organize. Tragedies such as the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist disaster in New York and the 1914 massacre of striking miners in Ludlow, Colorado, are seemingly behind us. But the pace and the reach of globalization have multiplied exponentially, as has the gap between capital and workers, and the gains of the New Deal and Progressive Era have been steadily disappearing. Such conditions have produced lived realities for today’s workers that resemble the exploitative nature of earlier eras, while involving new forms of repression. New consumer markets have come to expect quick and constant product adaptation; industry, in turn, demands a flexible workforce. Transportation and communications technologies now provide the means to create, and perpetuate, a low-wage workforce under constant threat.

For those industries that rely on a domestic workforce, the decimation of union representation and new forms of “flexible” employment that effectively evade employer liability give rise to a situation in which a worker’s rights are often theoretical. The illusory nature of workers’ rights, a fortified police state in an era when immigration enforcement budgets far exceed those of any other federal law enforcement agency (Meissner 2009), and relatively meager labor standards enforcement budgets combine to create a perfect storm of precarity that deters effective attempts to empower and mobilize immigrant workers. In sum, despite the proliferation of new laws and protections, the political will and practical ability to enforce them is often insufficient to address the rampant abuses the most vulnerable workers must confront.

The political sociologist Saskia Sassen has written an invaluable study for understanding the nature and impact of the current economic and political era in which we live. In Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy (2014), she details a series of predatory systems that disadvantage low-wage workers and that define the “brutal” logic of contemporary capitalism (4). What makes this system work so well is the illusion, and practical reality, that within the system there is no one at the helm and thus no one to be held accountable. As a result, even fair and well-meaning employers may engage in labor practices that, while firmly within the bounds of labor and employment law, are nevertheless exploitative. Moreover, as she shows, these practices then become the industry standard for any business owner hoping to turn a profit and stay competitive. While labor advocates have rallied for “high-road employment” that eschews such tactics, and there is ample evidence that worker-friendly practices can enhance productivity and coexist with profitable enterprise, it is also true that success stories are atypical (Milkman 2002). Unfortunately, low-road practices are the norm.

There has been much debate regarding the state of precarity in the modern era and what Guy Standing (2011, 2014) has labeled the “precariat,” a social class whose employment is marked by informality and increased insecurity.1 This state of precarity can be explained by several factors. In the United States, union membership has precipitously declined since the late 1970s, eroding worker protections. More recently, an economic recession sent unemployment rates soaring to 10 percent and triggered a housing crisis that disproportionately impacted communities of color. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that one in ten workers in 2014 was jobless for ninety-nine weeks or longer, with African Americans being the hardest hit (Kosanovich and Theodossiou 2015).

While the United States has begun to emerge from the recession, research on the “under-employed” casts doubt on even cautious descriptions of an economic recovery, especially for part-time workers of color (Shierholz 2013). Beyond the added income, full-time employment often provides important benefits that a subset of low-wage workers have come to rely on, such as health insurance and retirement accounts. Public benefits provide the only alternative for the rest of these low-wage workers. However, the last two decades have also ushered in a dismantling of the welfare state, which also largely excludes noncitizens (Park 2011) as well as other categories of “undeserving” workers, such as certain ex-prisoners (Travis 2005). The current reality therefore is that if one were to lose his or her job, even an undesirable one, there are few support systems on which to rely.2

Nonstandard employment relationships (Kalleberg 2000) and the continued erosion of the social contract (Katz 2010; Quinn Mills 1996) have dovetailed with a perceived explosion of foreign-born workers in the US labor force. While immigrants represented only 4.7 percent of the US population in 1970, this number rose to 13.1 percent in 2013 (Zong and Batalova 2015). However, looking back at the history of US immigration reveals an even higher proportion of foreign-born people at the turn of the twentieth century: 13.6 percent in 1900 versus 12.9 percent in 2010 (Migration Policy Institute 2015). Nevertheless, the recent increase has fueled the perception of an immigrant invasion, with a particular preoccupation with the southern border and a fear that immigrants are “stealing American jobs.” Ample research has debated the merits of this claim, with a focus on the complementarity versus substitutionality of immigrant workers. Restrictionists argue that any economic gains from immigration are limited and overstated (Borjas 2013), while recent evidence suggests that the inflow of foreign-born workers actually modestly increases wages for native-born workers (Greenstone and Looney 2012, 2010). In the legal arena, the courts continue to contemplate the rights of undocumented immigrants (Brownell 2011), and immigration debates have become increasingly inflammatory during the 2016 presidential campaign.

But if we shift our focus from the economy and immigration policies to the well-being of these individual workers, another set of key questions emerges. Rather than ask whether low-wage workers have contributed to the degradation of work in the United States—a question that Ruth Milkman (2006) has shown is much more complex than most histories allow—it seems more timely to ask how the exploitation of undocumented workers in particular is the canary in the coal mine for a global system built on precarity. Immigrant workers face particular challenges in the United States and across the world (Costello and Freedland 2014; Garcia 2012a). Immigrant labor is a symptom, not a cause, of domestic and global inequality.

To be sure, many foreign-born workers are engineers and doctors in the “high-skilled” workforce. But the contemporary US immigration flow is characterized by a “split personality” (Waldinger and Lichter 2003, 4); that is, although there are some high-skilled workers coming in, many more immigrants possess low levels of human capital, have limited proficiency in English, and are concentrated in low-wage service and production industries. Undocumented workers, who represent 5.4 percent of the national civilian workforce, are especially concentrated in precarious positions: a quarter of all workers in food processing, a third of all those in construction, and, depending on whose estimates you believe, anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of all farm labor in the United States (Passel 2006). These low-wage and conventionally “unskilled” immigrant workers possess key assets that employers in the secondary labor market covet, namely pliability. As Roger D. Waldinger and Michael I. Lichter (2003) write, “The best subordinates are those who know their place…. And where employers understand jobs to be demeaning… they have reasons to assign the task to a worker already unrespected…. Thus, jobs that require willing subordinates motivate employers to have recourse to immigrants” (40).

Undocumented workers occupy a paradoxical position in the US labor market. On the one hand, they are deportable “aliens,” and employers who hire them are subject to fines and criminal prosecution. On the other hand, they are a critical part of the workforce, and as easy targets for abuse, they also are an important outreach priority for labor standards enforcement agencies and advocates (Gleeson 2012a). The government then is at once responsible for policing and aiding undocumented workers. Yet increased immigration enforcement both at the worksite and in local communities fuels employer abuse (Menjívar and Abrego 2012). Along with at-will employment relationships, the threat of deportation creates a pliable workforce and discourages undocumented workers from speaking up. Immigrant workers are in a sense victims twice over. In a cruelly ironic twist, they are often blamed for the “spiraling crisis of global capitalism” that necessitates them leaving their communities of origin in the first place, then subsequently criminalized in their often hostile receiving communities (Robinson and Santos 2014; Milkman 2011). Nevertheless, as the data in this book reiterates, these workers are also agentic actors who are able and willing to mobilize their rights under the right conditions.

Precarious Claims examines how immigration enforcement efforts and at-will employment relationships jointly fuel the disposability of undocumented workers. I argue that, as with rosy presumptions about the post–civil rights era of workplace discrimination, legal equality for undocumented workers often veils deep-seated institutional inequalities. As such, I contend that undocumented status is a “precarity multiplier” that worsens workplace conditions (occupational segregation, pay differentials, lack of workplace safety); affects claimants’ experiences in the legal bureaucracy (lack of access to legal counsel, linguistic and cultural barriers, limited remedies); and limits access to a social safety net that already largely excludes undocumented immigrants.

THE REGIME OF INDIVIDUAL WORKERS’ RIGHTS

The system that shapes workplace protections in the United States dates back decades. Federal laws and agencies such as the National Labor Relations Act (1935), the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938), Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1964), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (1970) were all products of intense worker mobilizations and legislative debates. These arenas of protection—collective bargaining, wages and work hours, discrimination, and health and safety—compose a confusing matrix of bureaucracies that cover various statutes and geographic jurisdictions. For example, Alabama has no state minimum wage statute, while workers in Washington are currently entitled to $9.47 per hour, a rate that rises with inflation each year and is more than $2 more than the federal minimum. Meanwhile, cities across the country have instituted their own standards; take San Francisco, where wage rates are set to rise to $15 per hour by 2018.

However, neither the presence of workplace protection laws nor, indeed, active efforts to improve and strengthen them ensures that they are respected or that abusers will be held accountable. Moreover, these laws only regulate a narrow set of workplace behaviors, and there are many employer practices that, while perfectly legal, workers may nonetheless find unfair, exploitative, or otherwise harmful. Even within the realm of legal workplace violations, labor standards enforcement agencies face a wide range of challenges, from insufficient resources to short-staffed investigative units and, in some cases, lack of political will (Bernhardt et al. 2008; Government Accountability Office 2009; Kerwin and McCabe 2011). Furthermore, the claims-based system requires that workers know their rights and be willing to exercise them. In an increasingly de-unionized labor market where employers need little or no reason to fire a worker, filing a claim is a gamble most deem not worth taking. Even when workers do successfully pursue charges against an employer, their victories can ring hollow, as often they must then fight the employer to comply with a judge’s order (Cho, Koonse, and Mischel 2013).

This book goes beyond the simple story of employers seeking to maximize profit on the backs of their workers. Rather, it emphasizes the inequities that persist throughout the system of workplace justice and details workers’ experiences with a wide array of institutional gatekeepers. I home in on the cracks in these bureaucratic systems. Where does the system fall apart for aggrieved workers, and why, even in the best of circumstances, do workers often remain unprotected? The answer lies partly in the claims process. Beyond confronting their employers, workers must also learn to navigate complex management hierarchies, multifaceted government agencies, insurance companies, doctors, and language interpreters. Legal brokers, while essential to this process, encounter their own challenges, including a limited capacity to take on complex cases, fluctuating budgets, and staff turnover.

Employers have recently taken steps to make the claims-making process even more daunting. Despite the protections ensconced in federal and state law, firms have increasingly established a range of internal mechanisms to manage conflict between workers and management, often to the former’s disadvantage. Labor scholars and advocates have been critical of these internal processes, which are executed by sophisticated, some might say cunning, human resources departments. Discussing civil rights legislation, Lauren B. Edelman (1992) demonstrates how the ambiguity of antidiscrimination laws grants organizations “wide latitude” to comply in a way that gives the impression of earnest compliance while also meeting management’s interests. In the sexual harassment arena, Anna-Maria Marshall (2005) argues that company grievance procedures create obstacles to women’s efforts to assert their rights while shielding firms from legal liabilities. My findings highlight how logics of compliance and mediation can reduce the opportunities for restitution under the guise of procedural justice.3

Though we like to imagine it as such, the law is not a neutral institution; similarly, the process of claims-making is fraught with bias. Kitty Calavita and Valerie Jenness’s (2014) expert analysis of the prison grievance system reveals how the cards are stacked against many claimants from the beginning. Though they focus on a “total” institution that represents the full force of the state, the experiences of incarcerated individuals provide an important lens through which to observe how claims-making bureaucracies unfold. To begin, the grievance process, which the authors describe as “byzantine,” is designed for a closed environment where prisoners have few rights and fewer resources to exercise them. Despite the landmark creation of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (1996) and the inmate grievance system it created, these new rights have not ensured an easily accessible and efficient system. In fact, as the authors show through interviews with prison staff, the grievance system serves almost as a pressure valve for prisoner discontent—that is, to release pent-up frustrations without really addressing injustices. In a similar fashion, the creation of the individualized system of workers’ rights was, according to labor historians, an attempt to quell the discord prompted by the now-dying breed of social movement unionism (Fantasia and Voss 2004; Lichtenstein 2002). Again, such reforms are ultimately more concerned with avoiding conflict than establishing solid workplace protections.

Calavita and Jenness’s description of how the prisoner rights system was originally perceived sounds eerily familiar to the common critical perspective of labor rights activism. While most of the state agents they spoke to believed prisoners should have the rights outlined in the act, many also felt that the system had “gone too far” by being excessively generous toward the prisoners (Calavita and Jenness 2014, 110). Similarly, turn on a mainstream news channel today and you will hear voices warning against the dangers of granting a higher minimum wage, expanding overtime benefits, or adding discrimination protections and health and safety standards: decreased business innovation, trampled consumer rights, and curtailed corporate free speech. Like the prisoner grievance system, which is steeped in the logic of individual rights and carceral control, the labor standards enforcement bureaucracy must be understood within the logic of capitalism, which naturally limits workers’ rights even as it forms well-meaning, rational bureaucracies intended to enforce them.

These logics, the one exploitative and the other protective, often clash, and as such it should not be assumed that the predominant model of legal protection can ultimately eliminate economic and social inequality (Calavita and Jenness 2014, 3). Workers may create their own logics for defining harm that differ from those standards laid out under formal law. Marshall (2003), for example, highlights the deeply personal or extrajudicial agency that women invoke when deciding whether to pursue a legal claim against sexual harassment; these claimants may draw not on formal law but rather on notions of labor market productivity and feminist interpretations of power at the workplace. Similarly variable interpretations of workplace injustice can emerge in other violations, ranging from wage theft to workers’ compensation. This variability hinges in part on how workers learn about, interpret, and decide to mobilize the law as they develop their distinct legal consciousness.

LEGAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND DEPORTABILITY

My previous work examined how workers develop a legal consciousness about their rights and identified what factors keep them from coming forward with a claim (Gleeson 2010). The concept of legal consciousness has become somewhat shopworn in the field of law and society, but it is still useful for understanding how laws sustain their institutional power and how individuals understand their rights under the law and make decisions as to whether and how to exercise them (Silbey 2005, 2008). One’s position in the social and economic order can influence legal consciousness; for instance, poorer individuals (including nonwhites, who tend to be less affluent) engage lawyers and the courts less often. The negative effects of this imbalance are compounded because those with past experience in the system do better than first-timers (Galanter 1974; Curran 1977).4

In the arena of immigration, undocumented individuals (who are overwhelmingly Latino) are by definition excluded from full citizenship and actively pursued for expulsion by an ever-growing immigration enforcement apparatus. And yet undocumented workers have formed the core of many worker struggles (Milkman 2006) and will be crucial to any revitalization of labor unions. Therefore my claim is not that undocumented workers do not mobilize their rights, or that those who do cannot be successful. A quick scan of the press releases proudly disseminated by enforcement agencies and worker advocates reveals many high-profile, as well as more modest, victories. For example, Olivia Tamayo, an undocumented farm worker who was awarded more than $1 million after being repeatedly sexually assaulted by her employer, became an icon in the struggle against the impunity with which growers often operate in California’s Central Valley and across the nation (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2008). More recently, five female farmworkers in Florida were awarded more than $17 million after a federal jury found supervisors guilty of having forced them into “coerced sex, groping and verbal abuse, then fired them for objecting” (US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2015h). Beyond the discrimination arena, the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division’s EMPLEO program targets outreach to immigrant workers in the western region, many of whom are undocumented, and has helped ten thousand workers recover more than $15 million in back wages over the last ten years (Wage and Hour Division 2014b). Even the National Labor Relations Board, which is constrained by a Supreme Court ruling that prevents the reinstatement of undocumented workers, has certified union representation for many of those engaged in organizing (Jobs with Justice 2014).

It has been demonstrated across various institutional contexts, however, that despite certain protections and occasional victories, an immigrant’s relationship to the law is determined in large part by legal status, especially in the current uncertain policy environment. Migrant illegality represents a form of “legal violence” (Menjívar and Abrego 2012) against undocumented workers, even if the specific impacts may vary across age and institutional setting (Gleeson and Gonzales 2012; Abrego and Gonzales 2010), generation and family formation (Abrego 2014; Dreby 2010; Menjívar and Abrego 2009; Zatz and Rodriguez 2015), and the specifics of national origin and homeland politics (Coutin 2000; Golash-Boza 2015).5 The immigration enforcement apparatus, working in conjunction with a broad network of law enforcement at the state and local levels, implements a racialized dragnet of detention and removal that targets Latinos disproportionately (Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo 2013; Armenta 2015). Within the workplace context, the deportability of undocumented workers, despite expansive worker protection reforms at the federal, state, and local levels, is a looming reality for those engaged in claims-making.

Moreover, undocumented workers are not randomly distributed across the labor market; they are concentrated in certain areas whose risk factors can complicate their ability to seek and gain restitution. For example, undocumented workers are overrepresented in industries (e.g., certain agricultural fields, domestic labor) that are not covered by key government protections. Furthermore, undocumented workers are more likely to be misclassified as independent contractors (Carré 2015). Employers who classify them as such not only avoid paying taxes and other worker benefits but can also avoid adhering to many of the workplace standards afforded to employees. Undocumented workers are also generally more likely to work in dangerous occupations and don’t receive the concomitant wage differential to account for this risk (Hall and Greenman 2015). In addition to this labor force distribution, undocumented workers are more likely to have low levels of human capital and face English language limitations that pose instrumental barriers to filing a claim. Finally, as they are predominantly Latino, undocumented workers also face social discrimination that reflects and reinforces their racialized exclusion (De Genova 2005).

These structural barriers do not negate the strong efforts of worker advocates. Immigrant rights organizations, unions and worker centers, and both the pro bono and private bars have played an important role in improving the rights of low-wage workers by pushing for new laws and protections (such as raising the minimum wage and legislating rights for LGBT workers). These intermediaries are also crucial in helping these workers access these rights (Gordon 2007; Cummings 2009; Fine 2006; Zlolniski 2006). Existing research confirms that engaging with legal advocates can have a transformative impact on how marginalized individuals perceive, experience, and interact with the law (Hernández 2010). Yet, as this book reveals, the heroic efforts of these advocates are hampered by the shoestring budgets with which they operate, the limited remedies under the law, and the practical challenges posed by the behemoth bureaucracies that enforce the law and the quotidian struggles of low-wage workers’ lives.

DEFYING THE ODDS AND MAKING WORKERS’ RIGHTS REAL

There is a deep disjuncture between rights in theory and rights in practice, and the process of “making rights real” is fraught with challenges (Epp 2010). Consider one of the most common workplace violations: nonpayment, or underpayment, of wages. Let’s assume the violation occurred in California. In this case, California workers are covered at the federal level by the Fair Labor Standards Act, at the state level by the California Labor Code, and at the local level by an increasing number of municipalities that have enacted minimum wage ordinances of their own. Finding that their employer has not paid them what they are owed, and that their attempt to recoup their missing wages falls on deaf ears (or garners retaliation), workers may turn to the law to demand restitution. The first step in this process requires knowing enough about the law to know that they have been wronged. Next, workers must determine what to do with this knowledge. Perhaps they have learned where to go for help and which agency has jurisdiction—through a workers’ rights poster, conversations with coworkers, or a local organization’s outreach. Workers may then decide to visit a local labor organization, or some may even go to the government agency directly if they feel comfortable doing so. There, they will be asked to provide evidence that they worked the hours they claimed to have worked and any other documentation for the pay they received. If the employer did not keep records and paid in cash, and the workers cannot recall the specifics, they will be asked to provide their best estimate. Their legal advocate may also help them gather this information and attempt to contact the employer first to remedy the situation without having to file a formal claim. In some cases, a call from an attorney does the trick. In others, indignant (and occasionally cash-strapped) employers continue to evade and avoid.

Generally, an aggrieved worker will next decide if they have the energy and resources to file a formal claim at the labor commission, to which they would send the paperwork and await a settlement conference, which could take another six months. At that conference, the employer will ideally show up—they often do not—and with a neutral agent of the state present, sort out the facts of the claim. The employer may make an offer to make the issue go away, and the worker may counter (or the other way around). Either party may walk away. If nothing is settled, the parties are calendared for a formal hearing, which could be scheduled for up to a year later, and where, assuming all goes as planned, both parties and their advocates would again be present. At this point, the presiding officer or administrative law judge hears the evidence and renders a verdict. If at any point in the process either party requires translation, it will be provided. If the losing party disagrees with the decision, they may choose to appeal at superior court. If not, the decision is binding. If the worker wins the claim, the employer is expected to pay up. Lawyers, while not required, can give parties a crucial advantage at navigating the ins and outs of this process.

The details of a claims scenario certainly differ from statute to statute and agency to agency, but generally claims share the following qualities: 1) there are several places along the way where workers could ostensibly resolve their issue without ultimately pursuing a formal claim, even after initiating said claim; 2) workers may choose to proceed with or without the help of a legal advocate, a decision that hinges on social networks and resources available to the worker and could prove enormously consequential, especially for those who lack linguistic skills and experience with the legal process; 3) initiating a formal claim by no means precludes workers from dropping their claim at any point along the process and moving on with their lives.

We have limited data on when and how often workers initiate and complete a workplace claim. One difficulty is that the labor standards enforcement system is really a series of splintered bureaucracies that span federal, state, and (increasingly) local jurisdictions. Agencies enforce different statutes, rely on different data tracking systems, and sometimes don’t even define claims in the same way. To further complicate matters, these public agencies fiercely guard the confidentiality of their claimants, and rightly so. But as a result, it is nearly impossible to comprehensively measure all workplace violation claims at once, much less connect multiple claims that a worker may have, by relying on administrative data alone. Beyond these government agencies, the rise in internal dispute resolution systems and mandatory arbitration, even for nonunion workers, means that many claims may never get past a company’s human resources department.

However, some revealing data do exist that, at a minimum, help illustrate the challenges workers face in filing a claim. Several researchers have done the impressive work of tracking these claims through the “dispute pyramid,” and what they have found is alarming, though perhaps not surprising. Gary Blasi and Joseph W. Doherty (2010), for example, focused on administrative data from the Department of Fair Employment and Housing. To begin, they state a basic fact: for every one million employees in California, about 1,000 employment discrimination complaints are filed every year. Of these, 250 are filed with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; the other 750 go to the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH). Of these latter claims, 375 are granted a Notice of Right to Sue letter, where the claimant then has to rely on a private attorney. Continuing on, 165 of these cases will end up in court, but only 2 will receive a verdict. Another 375 (of the 750 DFEH cases) are pursued administratively by the agency.

The fates of these cases vary tremendously, but it is most important to note that of the 375 cases pursued by the agency, approximately 73 will be outright rejected for investigation, 33 will be dismissed for reasons unrelated to the merits of the case, 34 will request a Notice of Right to Sue letter to pursue claims outside the agency process, 20 will be dismissed due to insufficient evidence, 165 will be dismissed due to insufficient probable cause, and only 46 will be settled or resolved during the administrative process. In other words, claims can take many different paths and end in very different outcomes. In fact, according to Blasi and Doherty’s research, the odds of a complainant receiving a monetary award are one in fourteen, with a median award in the range of $3,000 to $4,000 when working through the administrative system. Those who proceed to the courts garner a median payout of $205,000 (with significant variation according to the basis of the claim, with race claims only garnering a median of $105,000) (Blasi and Doherty 2010).

These dynamics can be explained in part by what we already know from Max Weber about the function of bureaucracies, which can quickly harden into inflexible iron cages even as they purport to operate with objectivity, rationality, and fairness (Weber 2009, 1978). These hierarchical structures execute well-oiled systems governed by set rules meant to combat the biased and subjective approaches of an older, more nepotistic tradition. Yet despite this seemingly transparent system, and as the stories in this book reveal, not all workers are equally equipped to navigate these bureaucracies, even with help from advocates and state workers.6

Given the factors that keep workers from standing up for their rights, the workers in this study have already defied the odds and won a victory of sorts by coming forward in the first place. However, to expect the average worker to be “successful” in her claim proves fanciful given the reality revealed by these data. Of the 89 workers who completed a follow-up interview, only 43 reported filing a claim directly with a labor standards enforcement agency. Among those who chose not to, some happily reported that they were able to resolve the issue without a formal claim, but others cited reasons such as lacking the money to pay an attorney, the perception that the claim would lead to a “dead end,” the desire to get back to work and their normal lives, or simply the fact that they did not have a case that their legal advocate felt was worth pursuing. One respondent explained her rationale for dropping a claim despite feeling strongly about it: “I became discouraged, even though I know it was unjust.” Overall, when asked whether they had ultimately received what they wanted from their claim, only 16 of the 89 follow-up survey interviews provided an affirmative “yes.”

In part, such dissatisfaction motivates my study. The central goal of this book is to provide an account, from the ground up, of the context of worker precarity that leads to workplace violations, how workers weigh the costs and benefits of pursuing a claim, what resources they draw on to navigate the complex workers’ rights bureaucracies, and what impact these acts of legal mobilization ultimately have on their everyday lives.

THE COSTS OF PURSUING WORKERS’ JUSTICE

A unifying theme of this study is that engaging the law comes with costs, such that those with more capital (economic, social, cultural) have an easier time navigating and are more successful when they do. In this book I examine what actually happens once workers come forward. What propels a worker to file a claim given all the evidence we have about the barriers to claims-making? And once a worker has filed a formal claim, what challenges lie ahead? In short, filing a claim is a psychologically taxing process. Workers exercise agency to decide which violations to prioritize or disregard, how far to carry the fight, and when to settle and for what amount. To be sure, these decisions are structured by economic forces (attorney fees, financial situation, et cetera), but as life continues past the initial excitement of courageously coming forward to file a claim, everyday pressures continue to mount. Rent comes due, cars break down, children need care. The time commitment and opportunity costs of persisting in a claim can become just as burdensome as the financial costs. The truth is that it takes tenacity to pursue a claim to the end.

During the claims process, workers may also change their purpose and their goals for achieving justice. They may originally initiate a claim out of an affective stance rooted in general convictions of right and wrong, even if they do not really understand how the law protects them. Over time, they may turn to a more rational approach that weighs the costs and benefits of continuing to fight. Their engagement in the administrative process can lead claimants to “reformulate and reinterpret these problems, meanings, and consequences” (Merry 1990, 3). In my research, I found that one to three years after their initial claims were filed, workers had generally lost their initial reverence for the law, and along with it the hope of success via the formal system. Not every claimant persisted, and many sought alternative routes for justice (Ewick and Silbey 1998). Others came to reinterpret what they had previously understood to be a just outcome. Ellen Berrey, Steve G. Hoffman, and Laura Beth Nielsen (2012) refer to this contextual effect as “situated justice,” which depends a great deal on claimants’ economic circumstances and social context (legal status, job, age, and other factors).

This study asked workers to reflect on their claims-making experience on the heels of its conclusion, seeking to discover what claimants felt was gained and lost in the process. Many of the low-wage workers I spoke with had no desire to return to their original job, to which they generally had no allegiance. Yet many were also frustrated by their inability to find new employment in a recessionary (and even post-recessionary) environment. Those employed in industries with strong social networks were especially cognizant of the power their previous employer had to refuse a positive reference and essentially blacklist them. Workers had to engage with government bureaucrats and the many ancillary players in the system, including insurers, doctors, and interpreters. Finally, as I focused on claimants who had sought legal help in this process, I also investigated the role that attorneys play in shaping their experience. Complaints of perceived attorney incompetence, problems communicating with legal staff, prohibitive fees, and the challenges of pro se (unrepresented) litigation abounded. Just as important, workers repeatedly emphasized their expectations of respect from the system, their frustration in how the “objective” expertise of technocrats was elevated above their own experience, and ultimately the toll the claims process took on their personal lives.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

This research draws on the experiences of workers in the San Francisco Bay Area and Silicon Valley, one of the most affluent regions in the country. That region is also home to millions of low-wage workers who serve the needs of the postindustrial information economy. Northern California has a long history of immigrant labor, a vibrant civil society for immigrant and low-wage workers, and some of the most progressive policy environments in the country. Of the 8.4 million residents in the San Jose–San Francisco–Oakland CSA (combined statistical area), 44 percent do not identify as white, 26 percent identify as Hispanic or Latino, and 29 percent are foreign born.7 These immigrant workers are often concentrated in nonunion, low-pay, no-benefit jobs. Temporary and seasonal work is increasingly common, both in service work and in agriculture. An hour south of Silicon Valley along the Central Coast, the laborers in the fields of Watsonville and Salinas are almost entirely Latino immigrant workers, many of them undocumented. Whereas 5 percent of US workers are estimated to be undocumented, 7.8 percent of California workers have no authorization (Passel and Cohn 2009). These figures for undocumented workers vary widely throughout the state: only 3.7 percent in dense and expensive San Francisco, 8.4 percent in the East Bay (Alameda County), and 10.2 percent in Silicon Valley (Santa Clara County) (Hill and Johnson 2011).

My findings are based on three primary sources of data. In the first, I surveyed workers attending one of six workers’ rights clinics in the San Francisco Bay Area and Central Coast region. My team attended 93 separate clinic events and collected 469 surveys from June 2010 through April 2012. Of these, 385 workers agreed to a follow-up interview. Ultimately, we were able to contact 89 of them, who then participated in an in-depth interview 12 to 36 months after their initial survey. I supplement these data with a second sample: interviews with injured workers engaged in the process of filing a workers’ compensation claim. I recruited these claimants by attending 29 workshops (14 in English and 15 in Spanish) provided by the California Division of Workers’ Compensation in Oakland, Salinas, and San Jose between December 2008 and December 2013. In sum, I conducted formal interviews with 24 of these attendees. Lastly, my conclusions are based on my observations as a volunteer for a small legal aid clinic in a rural farmworker community on the Central Coast. From November 2010 to June 2014 I attended 40 clinics in total (25 dedicated to workers’ compensation, 14 dedicated to wage claims) where I interviewed workers (mostly in Spanish), consulted with attorneys, and offered advice to clients. Furthermore, I draw on formal interviews with agency staff, attorneys, and clinic volunteers across the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as my occasional visits with clients to their settlement conferences and hearings.

The nonprofit legal aid organizations I worked with were run mostly by law students and volunteers and staff attorneys. The organizations relied on support from local universities, foundations, and a wide variety of grants.8 They ran workers’ rights clinics on a regular basis, typically on weekday evenings. While the particular focus and capacity of each legal clinic varied, each saw cases involving wage theft, discrimination, sexual harassment, and workers’ compensation. The clinics also frequently helped workers who were appealing an unemployment claim denial or who had problems with their pensions. These clinics lasted several hours, and depending on capacity, anywhere from 5 to 20 workers would be scheduled to meet with a staff member (often a law student or other volunteer), who conducted an initial intake consultation. They then consulted with a supervising attorney who supplied advice, determined whether the clinic was in a position to provide follow-up assistance, and, if necessary, provided an outside referral.

Each clinic lasted between two and three hours. Our team approached workers while they waited for their initial consultation, in between their initial meeting and their follow-up advice session, or as they left their appointment. Workers were assured that they were free to opt out of our study and that their participation would in no way positively or negatively impact their ability to receive services from the center. The survey lasted approximately twenty to thirty minutes and included questions regarding workers’ employment history, the conditions that gave rise to their claim, and the resources and referrals they relied on prior to coming to the legal aid clinic. Each survey was conducted on site, and each respondent received a $15 gift card for their time. All but four interviews took place in person, and they lasted on average one hour. Interviewees were again incentivized with a $15 gift card, and, when appropriate, provided a beverage or meal (depending on the meeting place). Sixty interviews were conducted in Spanish, and one in Mandarin.9 During these interviews, respondents were asked to elaborate on the circumstances that led them to file a formal claim, what challenges they encountered, and whether they were satisfied with the final outcome. Pseudonyms are used for all references to respondent data.

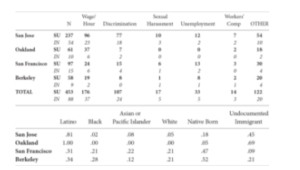

TABLE 1A: Key Survey Characteristics (Means)

Survey respondents represent the diverse communities that these legal aid organizations assist. Seventy-three percent of respondents are foreign born, two-thirds are Latino, and a small minority of workers identify as African American (9 percent), Asian/Pacific Islander (11 percent), and white (10 percent). I estimate that 37 percent of respondents are undocumented;10 of these, all but one identify as Latino. Nonetheless, the interviewed workers constitute an established immigrant population, with the average time in the United States being 17.6 years for documented and 12.3 years for undocumented respondents. Surveys were conducted mostly in English (186) and Spanish (262), but also in some cases in Mandarin (5). The respondents are low-wage workers with generally low levels of education—60 percent reporting a high school degree or less—and only half speak English. They are concentrated in the retail, day labor, and food service sectors, though some respondents were unemployed throughout the recession years. The distribution of these interviews is consistent with the original sample of survey respondents.

TABLE 1B: Distribution of Interviews and Follow-up Interviews by Nativity and Legal Status

TABLE 1C: Distribution of Claimant Characteristics Across Clinics (%)

NOTES:

•Race categories are not mutually exclusive.

•Claim categories are also not mutually exclusive. Percentages do not sum to 100; the residual category is “other” and includes allegations of wrongful termination.

•These claim categories reflect a worker’s initial declaration of their issue, but not necessarily what their claim evolved into, which could include, or be replaced by, other claim categories.

•SU = initial survey, IN = follow-up interview

•Totals do not include additional interviews with injured workers (workers’ compensation claim) who did not participate in the original survey, nor one follow-up interview with a survey respondent from a smaller clinic who participated in the pilot phase of the project.

This research was designed to examine the challenges that workers who have already ventured into the labor standards enforcement process continue to face. Therefore, the sample is not representative of the general low-wage worker population. By design, this survey sample represents those workers who are generally aware of their rights and who have begun the process of filing a formal claim. These are workers who, relative to their counterparts who have not come forward, likely possess more information and resources to make their claim successful. By returning to examine the experiences of workers beyond the initial stage of claims-making, my findings highlight the important but limited role of the labor standards enforcement bureaucracy for improving the conditions of low-wage workers.

Lastly, it is crucial to note that throughout the process I relied on the kindness and generosity of those willing to tell their stories. There were some challenges. I simply could not get hold of some claimants. One to three years is a long time in the life of a low-wage worker. People move, cell phone bills go unpaid, numbers change. Sometimes family members would agree to pass my message along, but rarely did I receive a call back. This is understandable, given that the prospect of sharing one’s story of struggle with a stranger defies logic. I am conscious that the time I took from workers—meeting in local coffee shops or in their homes—took away from time they could otherwise be spending with their families, sleeping, or tending to the demands of everyday life. To say that the opportunity to speak with me represented a welcome cathartic valve would be presumptuous and likely untrue for many of the workers. Moreover, I doubt that the modest honorarium I offered was a major incitement to come forward.

Several of the workers I was initially able to get on the phone explained the reasons why they could not speak with me. A few feared that the settlements they had negotiated would be at risk, despite all my assurances of confidentiality. Others, especially injured workers, were so traumatized by the long series of depositions, medical appointments, and bullying calls by insurers that they simply were wary of me and reluctant to engage further. Typically I attempted to reach individuals at least twice, erring on the side of respect for those not interested even though I realized that by doing so I would likely miss a few who needed some persistence. After two tries, I would mark the record closed and move on.

Usually people were firm but friendly, though on occasion my follow-up calls would be met with hostility and distrust. Not every worker I surveyed at the legal aid clinic was actually able to get help, depending on the merits of their case or the clinic’s inability to take on complex cases that really required private counsel. Facing a situation where help was unavailable, workers were sometimes resentful and declined to say more to me. A few workers were still in the thick of their cases, in a holding pattern with little to report. In some of those instances, I was able to follow up later on down the road.

The most common responses I received from workers who declined a follow-up interview, despite having originally consented, were that they were tired and ready to move on or had no time. In some cases, workers were too busy with their jobs or families to speak with me. Some immigrants had returned to their countries of origin, either for an extended stay or for good. In a handful of cases, I would show up for an interview and the respondent would never arrive. Oftentimes a sick family member, a last-minute work schedule change, or unreliable transportation was the culprit.

In sum, it is important to understand that the workers I ultimately was able to speak with were those who had the time, ability, and willingness to share their stories. Though I cannot be sure, my impression is that these cases were positively selected from the claims I did not get to explore. Our conversations focused primarily on the claim at hand, but often veered into broader discussions about the challenges associated with being a low-wage worker in one of the most expensive housing markets in the country. Because my data are based on retrospective discussions with workers, it is very possible, indeed probable, that the nonexpert claimants I spoke with had a poor understanding of the legal minutiae associated with their cases. In fact, the answer to even the simplest question—With which agency did you file your claim?—was not always apparent to the respondent. Was it with the federal or the state government? Did you go to superior court or just a settlement conference at the agency? In many cases, workers did not know. To the extent possible, I triangulated these data with interviews with attorneys and other advocates who deal with these types of cases on a regular basis. However, due to confidentiality concerns, I never discussed a specific case with an attorney at the clinic where the worker sought assistance, nor did I disclose enough information to reveal the identity of the claimant.

The strengths of these interviews are twofold: what they reveal about the claimants’ lay understanding of a complex system, and what they reveal about the impact that pursuing their case had on their everyday lives. While 60 percent of respondents had a high school degree or less, they were well-versed in the systems that governed their workplaces and gained a keen understanding of the biases inherent in the legal bureaucracies in which they had put their trust. It is their perspectives that I lean on the heaviest, with the hope that their insights will help illuminate the limits of formal labor law and how we must do better to address inequalities.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

The remainder of the book proceeds as follows. Chapter 2 begins by discussing the state of worker precarity today, and highlights the key differences from eras past. I then provide a brief overview of the current system of workers’ rights in the United States, as it also interacts with the immigration enforcement regime. Labor standards enforcement provides a useful case study for understanding how rights are implemented, the factors that shape legal consciousness, and the conditions required for workers to realize their rights. Successful claims are few and far between, and I preview how the long-term impacts of pursuing them can weigh heavily on a low-wage worker and his or her family. I end with a description of the data for this study, which includes survey data, interviews, and ethnographic observations.

Chapter 2 opens with the story of five workers engaged in the labor standards enforcement process whose experiences illuminate the range of challenges low-wage workers face, such as accessing benefits, negotiating autonomy on the shop floor, fomenting collective power, addressing harassment and abuse, and avoiding deportation. At-will employment also fuels worker precarity, as do nonstandard worker arrangements such as subcontracted and temporary positions. I describe how employers discipline workers via explicit and implicit threats, and a variety of administrative tools such as performance standards, periodic evaluations, and warnings that can quickly lead to dismissal. Social relationships, which may involve complicated management hierarchies, coworkers, and well-meaning but sometimes powerless unions, also shape workers’ experiences on the job.

Chapter 3 reviews the legal framework for enforcing the rights of low-wage workers in the United States. I critically examine the logics and the fissures plaguing the bureaucratic apparatus. I focus especially on employment law, including wage and hour standards, discrimination protections, workers’ compensation, and unemployment and state disability. I also briefly review the system of collective bargaining and the union grievance process. I emphasize the limits of statutory protections, as much of the exploitative practices that workers endure fall outside their purview. As such, the line blurs between legally prohibited employer abuses and accepted or overlooked coercive practices. I end with a brief overview of the negative impact of employer sanctions and immigration enforcement efforts on undocumented workers.

Chapter 4 follows the experiences of workers as they make their way through the bureaucracy. I begin by examining the logics that create a successful claim and how workers learn about the rights they do and do not have. I discuss the factors that ultimately shape a worker’s decision to come forward, and challenge the limited focus typically placed on rights education. I next unpack the various gatekeepers and brokers who manage the labor standards enforcement system, including government agents, private insurers and medical experts, language brokers, and attorneys. As workers navigate the bureaucracy, they must weigh the financial considerations, time and opportunity costs, and stress of the process in deciding whether to continue fighting and when to stop.

Chapter 5 focuses on the aftermath of workplace exploitation and legal mobilization, which can amplify existing precarity. I highlight three sets of consequences workers must cope with, including reinventing their professional identity and managing financial devastation, the impact on their physical and mental health, and the burden on their families here and abroad. I reflect too on those undocumented workers who grow tired of enduring abuse with no hope for immigration reform, and eventually return to their home countries. The chapter concludes by considering how workers take stock of their experiences as precarious workers navigating the claims bureaucracy. Some walk away enlightened and empowered, whereas many more find themselves resigned to the injustice and regretful for what they have lost in the process.

The book concludes by reflecting on how the current system of workers’ rights institutionalizes workplace precarity, and the deep divide between laws on the books and laws in practice. I highlight the importance of institutional intermediaries and increasing access to justice, and the limits of claims-driven enforcement approaches. As we march toward expanding the legal rights of individual workers, I call on us to consider also the many challenges workers face in realizing these protections. Immigration reform, while absolutely necessary, I caution is also insufficient to address worker precarity alone, as both undocumented and documented workers have much in common. I end by considering what this bottom-up perspective on rights mobilization reveals about precarity, agency, and the pursuit of justice.