31 The Rise of Andrew Jackson

The career of Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), the survivor of that backcountry Kentucky duel in 1806, exemplified both the opportunities and the dangers of political life in the early republic. A lawyer, slaveholder, and general—and eventually the seventh president of the United States—he rose from humble frontier beginnings to become one of the most powerful Americans of the nineteenth century.

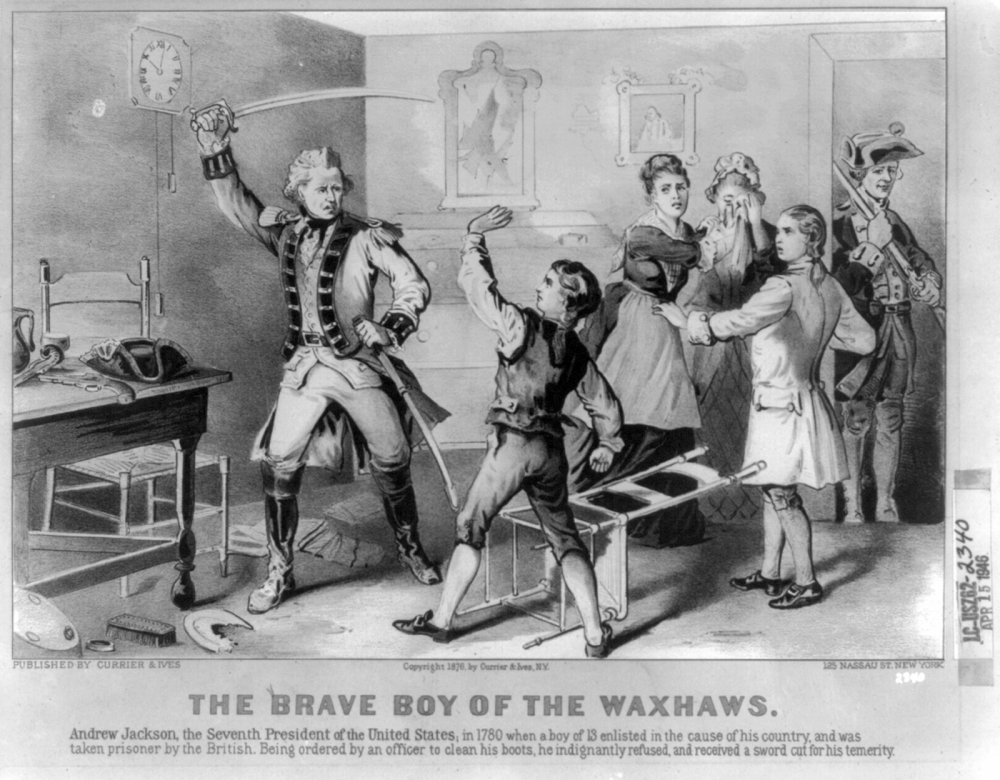

A child of Irish immigrants, Andrew Jackson was born on March 17, 1767, on the border between North and South Carolina. He grew up during dangerous times. At age thirteen, he joined an American militia unit in the Revolutionary War, but was soon captured, and a British officer slashed at his head with a sword after he refused to shine the officer’s shoes. Disease during the war had claimed the lives of his two brothers and his mother, leaving him an orphan. Their deaths and his wounds had left Jackson with a deep and abiding hatred of Great Britain.

After the war, Jackson moved west to frontier Tennessee, where despite his poor education, he prospered, working as a lawyer and acquiring land and slaves. (He would eventually come to keep 150 slaves at the Hermitage, his plantation near Nashville.) In 1796, Jackson was elected as a U.S. representative, and a year later he won a seat in the Senate, although he resigned within a year, citing financial difficulties.

Thanks to his political connections, Jackson obtained a general’s commission at the outbreak of the War of 1812. Despite having no combat experience, General Jackson quickly impressed his troops, who nicknamed him “Old Hickory” after a particularly tough kind of tree.

Jackson led his militiamen into battle in the Southeast, first during the Creek War, a side conflict that started between different factions of Muskogee (Creek) Indians in present-day Alabama. In that war, he won a decisive victory over hostile fighters at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. A year later, he also won a spectacular victory over a British invasion force at the Battle of New Orleans. There, Jackson’s troops—including backwoods militiamen, free African Americans, Indians, and a company of slave-trading pirates—successfully defended the city and inflicted more than 2,000 casualties against the British, sustaining barely 300 casualties of their own. The Battle of New Orleans was a thrilling victory for the United States, but it actually happened several days after a peace treaty was signed in Europe to end the war. News of the treaty had not yet reached New Orleans.

The end of the War of 1812 did not end Jackson’s military career. In 1818, as commander of the U.S. southern military district, Jackson also launched an invasion of Spanish-owned Florida. He was acting on vague orders from the War Department to break the resistance of the region’s Seminole Indians, who protected runaway slaves and attacked American settlers across the border. On Jackson’s orders in 1816, U.S. soldiers and their Creek allies had already destroyed the “Negro Fort,” a British-built fortress on Spanish soil, killing 270 former slaves and executing some survivors. In 1818, Jackson’s troops crossed the border again. They occupied Pensacola, the main Spanish town in the region, and arrested two British subjects, whom Jackson executed for helping the Seminoles. The execution of these two Britons created an international diplomatic crisis.

Most officials in President James Monroe’s administration called for Jackson’s censure. But Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the son of former President John Adams, found Jackson’s behavior useful. He defended the impulsive general, arguing that he had had been forced to act. Adams used Jackson’s military successes in this First Seminole War to persuade Spain to accept the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, which gave Florida to the United States.

Any friendliness between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, however, did not survive long. In 1824, four nominees competed for the presidency in one of the closest elections in American history. Each came from different parts of the country—Adams from Massachusetts, Jackson from Tennessee, William H. Crawford from Georgia, and Henry Clay from Kentucky. Jackson won more popular votes than anyone else. But with no majority winner in the Electoral College, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. There, Adams used his political clout to claim the presidency, persuading Clay to support him. Jackson would never forgive Adams, whom he accused of engineering a “corrupt bargain” with Clay to circumvent the popular will.

Four years later, in 1828, Adams and Jackson squared off in one of the dirtiest presidential elections to date. Pro-Jackson partisans accused Adams of elitism and claimed that while serving in Russia as a diplomat he had offered the Russian emperor an American prostitute. Adams’s supporters, on the other hand, accused Jackson of murder and attacked the morality of his marriage, pointing out that Jackson had unwittingly married his wife Rachel before the divorce on her prior marriage was complete. This time, Andrew Jackson won the election easily, but Rachel Jackson died suddenly before his inauguration. Jackson would never forgive the people who attacked his wife’s character during the campaign.

In 1828, Jackson’s broad appeal as a military hero won him the presidency. He was “Old Hickory,” the “Hero of New Orleans,” a leader of plain frontier folk. His wartime accomplishments appealed to many voters’ pride. In office over the next eight years, he would claim to represent the interests of ordinary white Americans, especially from the South and West, against the country’s wealthy and powerful elite. This attitude would lead him and his allies into a series of bitter political struggles.