37 The Benevolent Empire

After religious disestablishment, citizens of the United States faced a dilemma: how to cultivate a moral and virtuous public without aid from state-sponsored religion. Most Americans agreed that a good and moral citizenry was essential for the national project to succeed, but many shared the perception that society’s moral foundation was weakening. Narratives of moral and social decline, known as jeremiads, had long been embedded in Protestant story-telling traditions, but jeremiads took on new urgency in the antebellum period. In the years immediately following disestablishment, “traditional” Protestant Christianity was at low tide, while the Industrial Revolution and the spread of capitalism had led to a host of social problems associated cities and commerce. The Second Great Awakening was in part a spiritual response to such changes, revitalizing Christian spirits through the promise of salvation. The revivals also provided an institutional antidote to the insecurities of a rapidly changing world by inspiring an immense and widespread movement for social reform. Growly directly out of nineteenth-century revivalism, networks of reform societies proliferated throughout the United States between 1815 and 1861, melding religion and reform into a powerful force in American culture. This force is known as the “benevolent empire.”

The benevolent empire departed from revivalism’s early populism, as middle class ministers dominated the leadership of antebellum reform societies. As the Second Great Awakening gained momentum in the early nineteenth century, worshippers from the more “respectable” middle class began to eclipse the numbers of lower-class evangelicals. And, due to the economic forces of the market revolution, it was the middle-class evangelicals who had the time and resources to devote to reforming efforts. As labor shifted out of the household and into the factory, middle-class women, in particular, were freed from household labor and able to play a leading role in reform activity. They became increasingly responsible for the moral maintenance of their homes and communities, and their leadership signaled a dramatic departure from previous generations when such prominent roles for ordinary women would have been unthinkable.

Different forces within evangelical Protestantism combined to encourage reform. One of the great lights of benevolent reform was Charles Grandison Finney, the radical revivalist, who promoted a movement known as “perfectionism.” Premised on the belief that truly redeemed Christians would be motivated to live free of sin and reflect the perfection of God himself, his wildly popular revivals encouraged his converted followers to join reform movements. The idea of “disinterested benevolence” also turned many evangelicals toward reform. Preachers championing disinterested benevolence argued that true Christianity requires that a person give up self-love in favor of loving others. Though perfectionism and disinterested benevolence were the most prominent forces encouraging benevolent societies, some preachers achieved the same end in their advocacy of postmillennialism. In this worldview, Christ’s return was foretold to occur after humanity had enjoyed one thousand years’ peace, and it was the duty of converted Christians to improve the world around them in order to pave the way for Christ’s redeeming return. Though ideological and theological issues like these divided Protestants into more and more sects, church leaders often worked on an interdenominational basis to establish benevolent societies and draw their followers into the work of social reform.

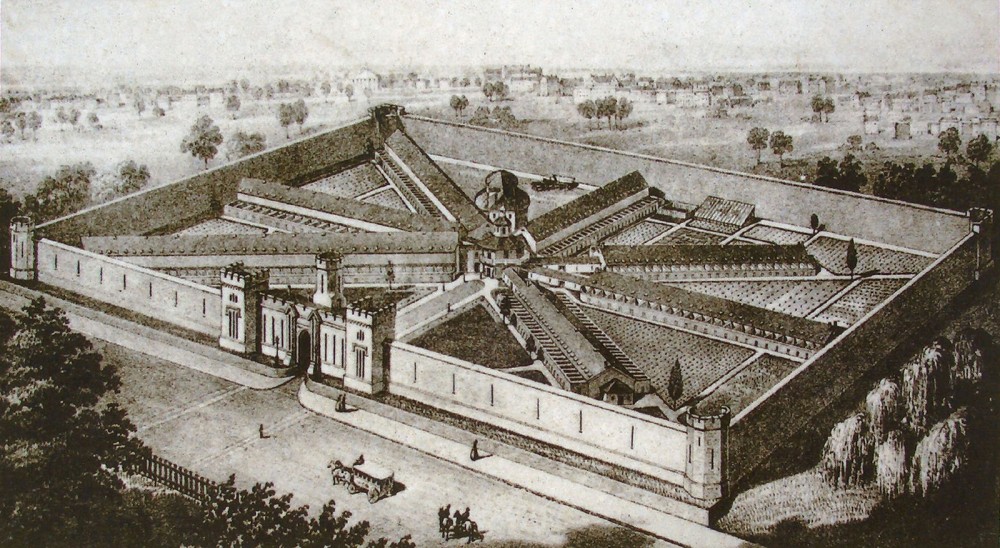

Under the leadership of preachers and ministers, moral reform societies attacked many social problems. Two significant reform movements, which will be discussed in detail in subsequent sections, were the antislavery movement and the crusade for women’s rights. Pervasive immoral behavior was also a major target, with societies tackling activities like gambling and dueling. Sabbatarians fought tirelessly to end non-religious activity on the Sabbath. Prostitution, in particular, became a major focus of reform in the 1830s as reformers in cities like New York attempted to stem the tide of urban sex work by establishing asylums for the redemption of “abandoned women.” Over the course of the antebellum period, voluntary associations and benevolent activists also worked to reform bankruptcy laws, prison systems, insane asylums, labor laws, and education. They built orphanages and free medical dispensaries, and developed programs to provide professional services like social work, job placement, and day camps for children in the slums. The evangelical effort to cure social problems through the foundation and reform of such wide-ranging establishments is often referred to as institutional salvation.

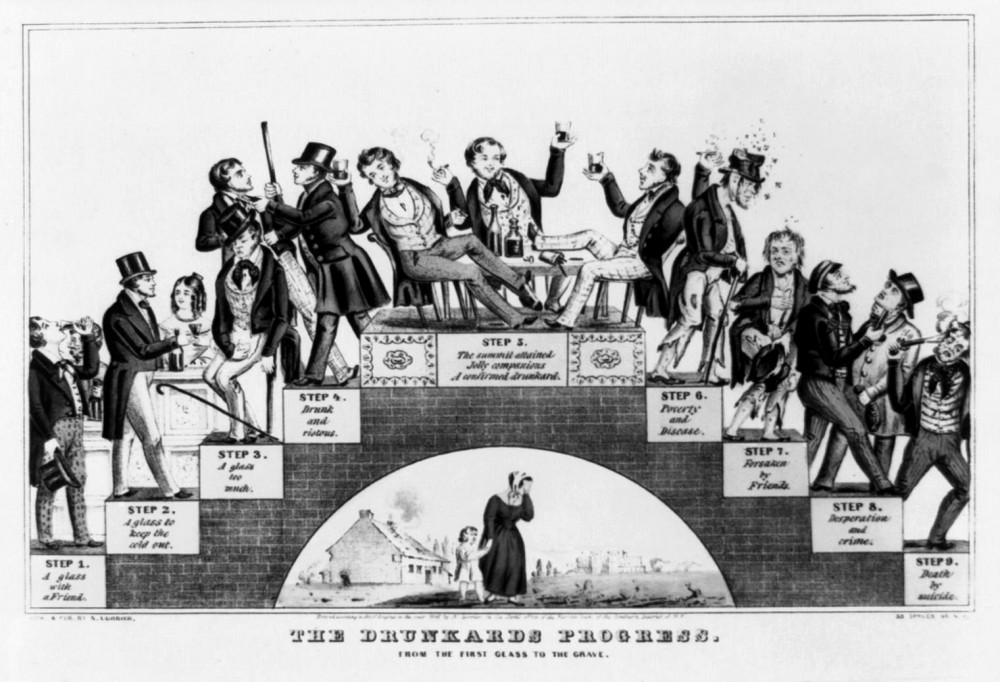

Among all the social reform movements associated with the benevolent empire, the temperance crusade was the most successful. Championed by prominent preachers like Lyman Beecher, the movement’s effort to curb the consumption of alcohol galvanized widespread support among the middle class. Alcohol consumption became a significant social issue after the American Revolution. Commercial distilleries produced readily available, cheap whiskey that was frequently more affordable than milk or beer and safer than water, and hard liquor became a staple beverage in many lower- and middle-class households. Consumption among adults skyrocketed in the early nineteenth century, and alcoholism had become an endemic problem across the United States by the 1820s. As alcoholism became an increasingly visible issue in towns and cities, most reformers escalated their efforts from advocating moderation in liquor consumption to full abstinence from all alcohol.

Many reformers saw intemperance as the biggest impediment to maintaining order and morality in the young republic. Temperance reformers saw a direct correlation between alcohol and other forms of vice targeted by voluntary societies, and, most importantly, felt that it endangered family life. So, in 1826, evangelical ministers organized the American Temperance Society (ATS) to help spread the crusade more effectively on a national level. The ATS supported lecture campaigns, produced temperance literature, and organized revivals specifically aimed at encouraging worshippers to give up the drink. It was so successful that, within a decade, it established five thousand branches and grew to over a million members. Temperance reformers pledged not to touch the bottle, and canvassed their neighborhoods and towns to encourage others to join their “Cold Water Army.” They also targeted the law, successfully influencing lawmakers in several states to prohibit the sale of liquor.

In response to the perception that heavy drinking was associated with men who abused, abandoned, or neglected their family obligations, women formed a significant presence in societies dedicated to eradicating liquor. Temperance became a hallmark of middle-class respectability among both men and women and developed into a crusade with a visible class character. As with many of the reform efforts championed by the middle class, temperance threatened to intrude on the private family life of lower-class workers, many of whom were Irish Catholics. Such intrusions by the Protestant middle-class exacerbated class and religious tensions. Still, while the temperance movement made less substantial inroads into lower-class workers’ heavy-drinking social culture, the movement was still a great success for the reformers. In the 1830s, Americans drank half of what they had in the 1820s, and per capita consumption continued to decline over the next two decades.

Though middle-class reformers worked tirelessly to cure all manner of social problems through institutional salvation and voluntary benevolent work, they regularly participated in religious organizations founded explicitly to address the spiritual mission at the core of evangelical Protestantism. In fact, for many reformers, it was actually the experience of evangelizing among the poor and seeing firsthand the rampant social issues plaguing life in the slums that first inspired them to get involved in benevolent reform projects. Modeling themselves on the British and Foreign Bible Society, formed in 1804 to spread Christian doctrine to the British working class, urban missionaries emphasized the importance of winning the world for Christ, one soul at a time. For example, the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society used the efficient new steam-powered printing press to distribute bibles and evangelizing religious tracts throughout the United States. Historian Steven Mintz has suggested that the New York Religious Tract Society alone managed to distribute religious tracts to all but 388 of New York City’s 28,383 families. In places like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, middle-class women also established groups specifically to canvass neighborhoods and bring the gospel to lower-class “wards.”

Such evangelical missions extended well beyond the urban landscape, however. Stirred by nationalism and moral purpose, evangelicals labored to make sure the word of God reached far-flung settlers on the new American frontier. The American Bible Society distributed thousands of Bibles to frontier areas where churches and clergy were scarce, while the American Home Missionary Society provided substantial financial assistance to frontier congregations struggling to achieve self-sufficiency. Missionaries even worked to translate the Bible into Iroquois in order to more effectively evangelize Native American populations. As efficient printing technology and faster transportation facilitated new transatlantic and global connections, religious Americans also began to flex their missionary zeal on a global stage. In 1810, for example, Presbyterian and Congregationalist leaders established the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to evangelize in India, Africa, East Asia, and the Pacific.

The potent combination of social reform and evangelical mission at the heart of the nineteenth century’s benevolent empire produced reform agendas and institutional changes that have reverberated through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. By devoting their time to the moral uplift of their communities and the world at large, middle-class reformers created many of the largest and most influential organizations in the nation’s history. For the optimistic, religiously motivated American, no problem seemed to great to solve. Although one issue proved more explosively divisive than all the rest. That problem, of course, was slavery.