51 The Election of 1864 and Emancipation

The presidential contest of 1864 featured a transformed electorate. Three new states (West Virginia, Nevada, and Kansas) had been added since 1860 while the eleven states of the Confederacy did not participate.

Lincoln and his Vice President, Andrew Johnson (Tennessee), ran as nominees of the National Union Party. The main competition came from his former commander, General George B. McClellan. Though McClellan himself was a “War Democrat,” the official platform of the Democratic Party in 1864 revolved around negotiating an immediate end to the Civil War. McClellan’s Vice Presidential nominee was George H. Pendleton of Ohio—a well-known “Peace Democrat.”

On Election Day—November 8, 1864—Lincoln and McClellan each needed 117 electoral votes (out of a possible 233) to win the presidency. For much of the ’64 campaign season, Lincoln downplayed his chances of reelection and McClellan assumed that large numbers of Union soldiers would grant him support. However, thanks in great part to William T. Sherman’s military victories in Georgia, which included the fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, and overwhelming support from Union troops, Lincoln won the election easily. Additionally, Lincoln received support from more radical Republican factions (such as John C. Fremont and members of the Radical Democracy Party) that demanded the end of slavery.

In the popular vote, Lincoln crushed McClellan by a margin of 55.1% to 44.9%. In the Electoral College, Lincoln’s victory was even more pronounced at a margin of 212 to 21. As Lincoln won twenty-two states, McClellan only managed to carry three: New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky.

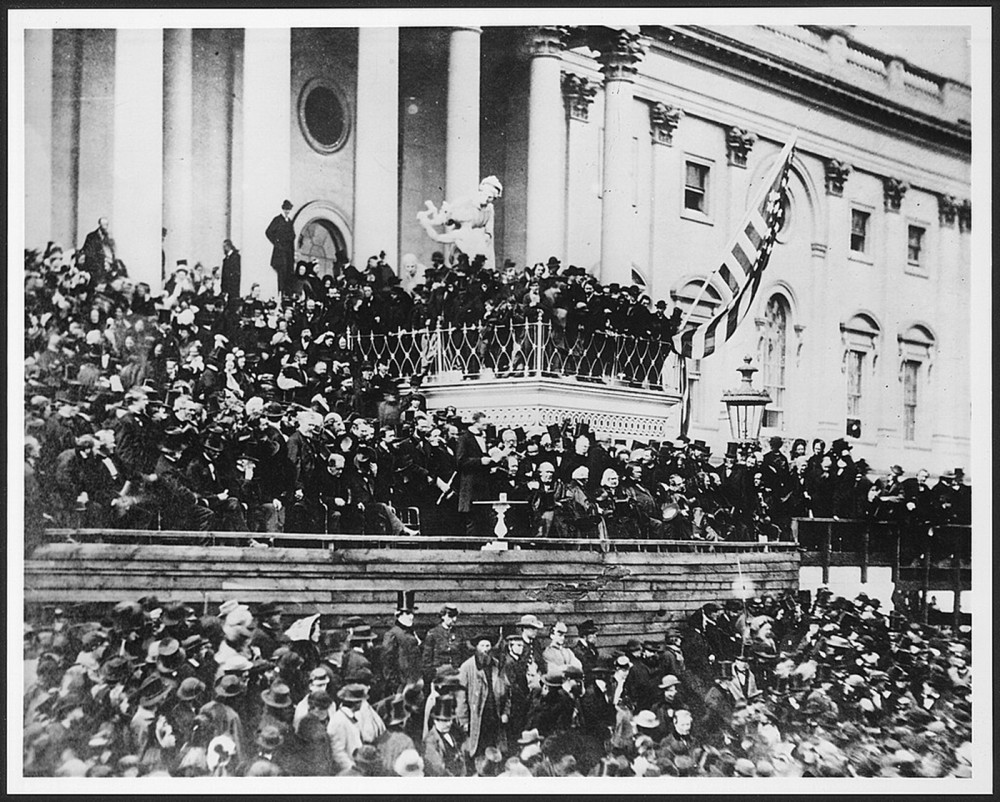

In the wake of reelection, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address on March 5, 1865, in which he concluded:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Emancipation played a major role in the election and the war. Yet, Abraham Lincoln did not abolish slavery with the stroke of his pen, nor should he be celebrated with the title of the “Great Emancipator.” While Lincoln played a leading role, the accolades bestowed upon him by contemporaries and subsequent generations obscure the elaborate process by which numerous actors in the Congress, the military, and enslaved people themselves brought about emancipation.

Of course, abolitionists had long struggled to obtain freedom for enslaved persons, but the war brought them unexpected allies. Politically, the roots of emancipation can be found in the First Confiscation Act of 1861. Republicans in Congress authorized military officials to do the actual work of freeing enslaved persons, a process called military emancipation. With each military victory, beginning with naval actions along the Atlantic seaboard, the U.S. military deployed constitutional measures to seize contraband. In August, General John C. Fremont declared all enslaved people in Missouri to be free, while General Benjamin Butler emancipated hundreds at Fortress Monroe in Virginia. Lincoln condemned Fremont’s actions, but Butler’s became military policy.

Rank-and-file soldiers and sailors pushed beyond the mandate of the law. Most Union soldiers had never before encountered enslaved people. In their diaries and their sketchbooks, soldiers and sailors recorded their interactions with newly freed African Americans, legitimating an essential humanity that would find popular reverberations in newspapers and magazines. Moreover, the increasingly visual culture of the 1860s in the North relied on photographs and sketches of the freedmen to provide evidence not only of their abuse at the hand of southern slaveholders, but also of their resilience and determination to resist them.

Perhaps most important to bringing about emancipation were the enslaved people themselves, who remained ever vigilant for opportunities to gain freedom. This process unfolded unevenly and violently, with African American women often playing leading roles in community organization. In a sense, these efforts can be seen as extensions of earlier tactics of resistance, but the events of the Civil War presented unprecedented opportunities for new and more lasting forms of fighting back. Once free, African Americans continued to work of freedom by enlisting in the Union army, supporting military efforts of their liberators, and, in time, supporting political measures that enabled their full civil rights.

To ensure the permanent legal end of slavery, Republicans drafted the Thirteenth Amendment during the war. Yet the end of legal slavery did not mean the end of racial injustice. During the war, ex-slaves were often segregated into disease-ridden contraband camps. After the war, the Republican Reconstruction program of guaranteeing black rights succumbed to persistent racism and southern white violence. Long after 1865, most black southerners continued to labor on plantations, albeit as nominally free tenants or sharecroppers, while facing public segregation and voting discrimination. The effects of slavery persisted long after emancipation.