27 Reading: The Meanings of Federalism

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How has the meaning of federalism changed over time?

- Why has the meaning of federalism changed over time?

- What are states’ rights and dual, cooperative, and competitive federalism?

The meaning of federalism has changed over time. During the first decades of the republic, many politicians held that states’ rights allowed states to disobey any national government that in their view exceeded its powers. Such a doctrine was largely discredited after the Civil War. Then dual federalism, a clear division of labor between national and state government, became the dominant doctrine. During the New Deal of the 1930s, cooperative federalism, whereby federal and state governments work together to solve problems, emerged and held sway until the 1960s. Since then, the situation is summarized by the term competitive federalism, whereby responsibilities are assigned based on whether the national government or the state is thought to be best able to handle the task.

States’ Rights

The ink had barely dried on the Constitution when disputes arose over federalism. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton hoped to build a strong national economic system; Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson favored a limited national government. Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian factions in President George Washington’s cabinet led to the first political parties: respectively, the Federalists, who favored national supremacy, and the Republicans, who supported states’ rights.

Compact Theory

In 1798, Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, outlawing malicious criticism of the government and authorizing the president to deport enemy aliens. In response, the Republican Jefferson drafted a resolution passed by Kentucky’s legislature, the first states’ rights manifesto. It set forth a compact theory, claiming that states had voluntarily entered into a “compact” to ratify the Constitution. Consequently, each state could engage in “nullification” and “judge for itself” if an act was constitutional and refuse to enforce it.[1] However, Jefferson shelved states’ rights when, as president, he directed the national government to purchase the enormous Louisiana Territory from France in 1803.

Links: Alien and Sedition Acts; Jefferson’s Role

Read more about the Alien and Sedition Acts online.

Read more about Jefferson’s role online.

Slavery and the Crisis of Federalism

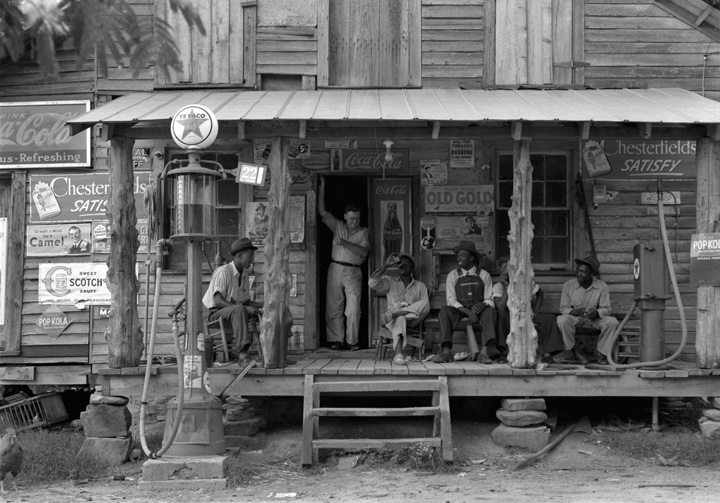

After the Revolutionary War, slavery waned in the North, where slaves were domestic servants or lone farmhands. In the South, labor-intensive crops on plantations were the basis of Southern prosperity, which relied heavily on slaves.[2]

In 1850, Congress faced the prospect of new states carved from land captured in the Mexican War and debated whether they would be slave or free states. In a compromise, Congress admitted California as a free state but directed the national government to capture and return escaped slaves, even in free states. Officials in Northern states decried such an exertion of national power favoring the South. They passed state laws outlining rights for accused fugitive slaves and forbidding state officials from capturing fugitives.[3] The Underground Railroad transporting escaped slaves northward grew. The saga of hunted fugitives was at the heart of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which sold more copies proportional to the American population than any book before or since.

In 1857, the Supreme Court stepped into the fray. Dred Scott, the slave of a deceased Missouri army surgeon, sued for freedom, noting he had accompanied his master for extended stays in a free state and a free territory.[4] The justices dismissed Scott’s claim. They stated that blacks, excluded from the Constitution, could never be U.S. citizens and could not sue in federal court. They added that any national restriction on slavery in territories violated the Fifth Amendment, which bars the government from taking property without due process of law. To many Northerners, the Dred Scott decision raised doubts about whether any state could effectively ban slavery. In December 1860, a convention in South Carolina repealed the state’s ratification of the Constitution and dissolved its union with the other states. Ten other states followed suit. The eleven formed the Confederate States of America.

Links: The Underground Railroad and the Dred Scott Case

Learn more about the Underground Railroad online.

Learn more about the Dred Scott case from the Library of Congress.

Enduring Image: The Confederate Battle Flag

The American flag is an enduring image of the United States’ national unity. The Civil War battle flag of the Confederate States of America is also an enduring image, but of states’ rights, of opposition to a national government, and of support for slavery. The blue cross studded with eleven stars for the states of the Confederacy was not its official flag. Soldiers hastily pressed it into battle to avoid confusion between the Union’s Stars and Stripes and the Confederacy’s Stars and Bars. After the South’s defeat, the battle flag, often lowered for mourning, was mainly a memento of gallant human loss.[5]

The flag’s meaning was transformed in the 1940s as the civil rights movement made gains against segregation in the South. One after another Southern state flew the flag above its capitol or defiantly redesigned the state flag to incorporate it. Over the last sixty years, a myriad of meanings arousing deep emotions have become attached to the flag: states’ rights; Southern regional pride; a general defiance of big government; nostalgia for a bygone era; racist support of segregation; or “equal rights for whites.”[6]

The battle flag appeals to politicians seeking resonant images. But its multiple meanings can backfire. In 2003, former Vermont governor Howard Dean, a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, addressed the Democratic National Committee and said, “White folks in the South who drive pickup trucks with Confederate flag decals on the back ought to be voting with us, and not them [Republicans], because their kids don’t have health insurance either, and their kids need better schools too.” Dean received a rousing ovation, so he probably thought little of it when he told the Des Moines Register, “I still want to be the candidate for guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks.”[7] Dean, the Democratic front runner, was condemned by his rivals who questioned his patriotism, judgment, and racial sensitivity. Dean apologized for his remark.[8]

The South’s defeat in the Civil War discredited compact theory and nullification. Since then, state officials’ efforts to defy national orders have been futile. In 1963, Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama to resist a court order to desegregate the all-white school. Eventually, he had no choice but to accede to federal marshals. In 1994, Pennsylvania governor Robert Casey, a pro-life Democrat, decreed he would not allow state officials to enforce a national order that state-run Medicaid programs pay for abortions in cases of rape and incest. He lost in court.[9]

Dual Federalism

After the Civil War, the justices of the Supreme Court wrote, “The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States.”[10] They endorsed dual federalism, a doctrine whereby national and state governments have clearly demarcated domains of power. The national government is supreme, but only in the areas where the Constitution authorizes it to act.

The basis for dual federalism was a series of Supreme Court decisions early in the nineteenth century. The key decision was McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). The Court struck down a Maryland state tax on the Bank of the United States chartered by Congress. Chief Justice Marshall conceded that the Constitution gave Congress no explicit power to charter a national bank,[11] but concluded that the Constitution’s necessary-and-proper clause enabled Congress and the national government to do whatever it deemed “convenient or useful” to exercise its powers. As for Maryland’s tax, he wrote, “the power to tax involves the power to destroy.” Therefore, when a state’s laws interfere with the national government’s operation, the latter takes precedence. From the 1780s to the Great Depression of the 1930s, the size and reach of the national government were relatively limited. As late as 1932, local government raised and spent more than the national government or the states.

On two subjects, however, the national government increased its power in relationship to the states and local governments: sin and economic regulation.

Link: McCulloch v. Maryland

Read more about McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) online.

The Politics of Sin

National powers were expanded when Congress targeted obscenity, prostitution, and alcohol.[12] In 1872, reformers led by Anthony Comstock persuaded Congress to pass laws blocking obscene material from being carried in the U.S. mail. Comstock had a broad notion of sinful media: all writings about sex, birth control, abortion, and childbearing, plus tabloid newspapers that allegedly corrupted innocent youth.

As a result of these laws, the national government gained the power to exclude material from the mail even if it was legal in individual states.

The power of the national government also increased when prostitution became a focus of national policy. A 1910 exposé in McClure’s magazine roused President William Howard Taft to warn Congress about prostitution rings operating across state lines. The ensuing media frenzy depicted young white girls torn from rural homes and degraded by an urban “white slave trade.” Using the commerce clause, Congress passed the Mann Act to prohibit the transportation “in interstate commerce…of any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”[13] The bill turned enforcement over to a tiny agency concerned with antitrust and postal violations, the Bureau of Investigations. The Bureau aggressively investigated thousands of allegations of “immoral purpose,” including unmarried couples crossing state lines to wed and interracial married couples.

The crusade to outlaw alcohol provided the most lasting expansion of national power. Reformers persuaded Congress in 1917 to bar importation of alcohol into dry states, and, in 1919, to amend the Constitution to allow for the nationwide prohibition of alcohol. Pervasive attempts to evade the law boosted organized crime, a rationale for the Bureau of Investigations to bloom into the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the equivalent of a national police force, in the 1920s.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933. But the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, its director from the 1920s to the 1970s, continued to call attention through news and entertainment media to the scourge of organized crime that justified its growth, political independence, and Hoover’s power. The FBI supervised film depictions of the lives of criminals like John Dillinger and long-running radio and television shows like The FBI. The heroic image of federal law enforcement would not be challenged until the 1960s when the classic film Bonnie and Clyde romanticized the tale of two small-time criminals into a saga of rebellious outsiders crushed by the ominous rise of authority across state lines.

Economic Regulation

Other national reforms in the late nineteenth century that increased the power of the national government were generated by reactions to industrialization, immigration, and urban growth. Crusading journalists decried the power of big business. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed miserable, unsafe working conditions in America’s factories. These reformers feared that states lacked the power or were reluctant to regulate railroads, inspect meat, or guarantee food and drug safety. They prompted Congress to use its powers under the commerce clause for economic regulation, starting with the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887 to regulate railroads and the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 to outlaw monopolies.

The Supreme Court, defending dual federalism, limited such regulation. It held in 1895 that the national government could only regulate matters directly affecting interstate commerce.[14] In 1918, it ruled that Congress could not use the commerce clause to deal with local matters like conditions of work. The national government could regulate interstate commerce of harmful products such as lottery tickets or impure food.[15] A similar logic prevented the U.S. government from using taxation powers to the same end.[16]

Cooperative Federalism

The massive economic crises of the Great Depression tolled the death knell for dual federalism. In its place, cooperative federalism emerged. Instead of a relatively clear separation of policy domains, national, state, and local governments would work together to try to respond to a wide range of problems.

The New Deal and the End of Dual Federalism

Elected in 1932, Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) sought to implement a “New Deal” for Americans amid staggering unemployment. He argued that the national government could restore the economy more effectively than states or localities. He persuaded Congress to enact sweeping legislation. New Deal programs included boards enforcing wage and price guarantees; programs to construct buildings and bridges, develop national parks, and create artworks; and payments to farmers to reduce acreage of crops and stabilize prices.

By 1939, national government expenditures equaled state and local expenditures combined.[17] FDR explained his programs to nationwide audiences in “fireside chats” on the relatively young medium of radio. His policies were highly popular, and he was reelected by a landslide in 1936. The Supreme Court, after rejecting several New Deal measures, eventually upheld national authority over such once-forbidden terrain as labor-management relations, minimum wages, and subsidies to farmers.[18] The Court thereby sealed the fate of dual federalism.

Links: The New Deal and Fireside Chats

Learn more about the New Deal online.

Read the Fireside Chats online.

Grants-in-Aid

Cooperative federalism’s central mechanisms were grants-in-aid: the national government passes funds to the states to administer programs. Starting in the 1940s and 1950s, national grants were awarded for infrastructure (airport construction, interstate highways), health (mental health, cancer control, hospital construction), and economic enhancement (agricultural marketing services, fish restoration).[19]

Grants-in-aid were cooperative in three ways. First, they funded policies that states already oversaw. Second, categorical grants required states to spend the funds for purposes specified by Congress but gave them leeway on how to do so. Third, states’ and localities’ core functions of education and law enforcement had little national government supervision.[20]

Competitive Federalism

During the 1960s, the national government moved increasingly into areas once reserved to the states. As a result, the essence of federalism today is competition rather than cooperation.[21]

Judicial Nationalizing

Cooperative federalism was weakened when a series of Supreme Court decisions, starting in the 1950s, caused states to face much closer supervision by national authorities. As you’ll see, the Court extended requirements of the Bill of Rights and of “equal protection of the law” to the states.

The Great Society

In 1963, President Lyndon Johnson proposed extending the New Deal policies of his hero, FDR. Seeking a “Great Society” and declaring a “War on Poverty,” Johnson inspired Congress to enact massive new programs funded by the national government. Over two hundred new grants programs were enacted during Johnson’s five years in office. They included a Jobs Corps and Head Start, which provided preschool education for poor children.

The Great Society undermined cooperative federalism. The new national policies to help the needy dealt with problems that states and localities had been unable or reluctant to address. Many of them bypassed states to go straight to local governments and nonprofit organizations.[22]

Link: The Great Society

Read more about The Great Society.

Obstacles and Opportunities

In competitive federalism, national, state, and local levels clash, even battle with each other.[23] Overlapping powers and responsibilities create friction, which is compounded by politicians’ desires to get in the news and claim credit for programs responding to public problems.

Competition between levels of federalism is a recurring feature of films and television programs. For instance, in the eternal television drama Law and Order and its offshoots, conflicts between local, state, and national law enforcement generate narrative tension and drama. This media frame does not consistently favor one side or the other. Sometimes, as in the film The Fugitive or stories about civil rights like Mississippi Burning, national law enforcement agencies take over from corrupt local authorities. Elsewhere, as in the action film Die Hard, national law enforcement is less competent than local or state police.

Mandates

Under competitive federalism, funds go from national to state and local governments with many conditions—most notably, directives known as mandates.[24] State and local governments want national funds but resent conditions. They especially dislike “unfunded mandates,” according to which the national government directs them what to do but gives them no funds to do it.

After the Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1994 elections, they passed a rule to bar unfunded mandates. If a member objects to an unfunded mandate, a majority must vote to waive the rule in order to pass it. This reform has had little impact: negative news attention to unfunded mandates is easily displaced by dramatic, personalized issues that cry out for action. For example, in 1996, the story of Megan Kanka, a young New Jersey girl killed by a released sex offender living in her neighborhood, gained huge news attention. The same Congress that outlawed unfunded mandates passed “Megan’s Law”—including an unfunded mandate ordering state and local law enforcement officers to compile lists of sex offenders and send them to a registry run by the national government.

Key Takeaways

Federalism in the United States has changed over time from clear divisions of powers between national, state, and local governments in the early years of the republic to greater intermingling and cooperation as well as conflict and competition today. Causes of these changes include political actions, court decisions, responses to economic problems (e.g., depression), and social concerns (e.g., sin).

- Forrest McDonald, States’ Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio, 1776–1876 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 38–43. ↵

- This section draws on James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). ↵

- Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780–1861 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974). ↵

- An encyclopedic account of this case is Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978). ↵

- See especially Robert E. Bonner, Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002). ↵

- For overviews of these meanings see Tony Horwitz,Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Random House, 1998) and J. Michael Martinez, William D. Richardson, and Ron McNinch-Su, eds., Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2000). ↵

- All quotes come from “Dems Battle over Confederate Flag,” CNN, November 2, 2003. ↵

- “Dean: ‘I Apologize’ for Flag Remark,” CNN, November 7, 2003. ↵

- David L. Shapiro, Federalism: A Dialogue (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1995), 98 n. 139. ↵

- Texas v. White, 7 Wall. 700 (1869). ↵

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819). ↵

- This section draws on James A. Morone, Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), chaps. 8–11. ↵

- Quoted in James A. Morone, Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 266. ↵

- United States v. E. C. Knight, 156 US 1 (1895). ↵

- Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 US 251 (1918). ↵

- Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Company, 259 US 20 (1922). ↵

- Thomas Anton, American Federalism & Public Policy: How the System Works (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988), 41. ↵

- Respectively, National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel, 301 US 1 (1937); United States v. Darby, 312 US 100 (1941); Wickard v. Filburn, 317 US 111 (1942). ↵

- David B. Walker, The Rebirth of Federalism: Slouching toward Washington(Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1999), 99. ↵

- Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), 17. ↵

- Paul E. Peterson, Barry George Rabe, and Kenneth K. Wong, When Federalism Works (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1986), especially chap. 5; Martha Derthick, Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), chap. 10. ↵

- David B. Walker, The Rebirth of Federalism: Slouching toward Washington (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1999), 123–25. ↵

- The term “competitive federalism” is developed in Thomas R. Dye, American Federalism: Competition among Governments (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990). ↵

- This definition is drawn from Michael Fix and Daphne Kenyon, eds., Coping with Mandates: What Are the Alternatives? (Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 1988), 3–4. ↵