264 The Phosphorus Cycle

Learning Outcomes

- Discuss the phosphorus cycle and phosphorus’s role on Earth

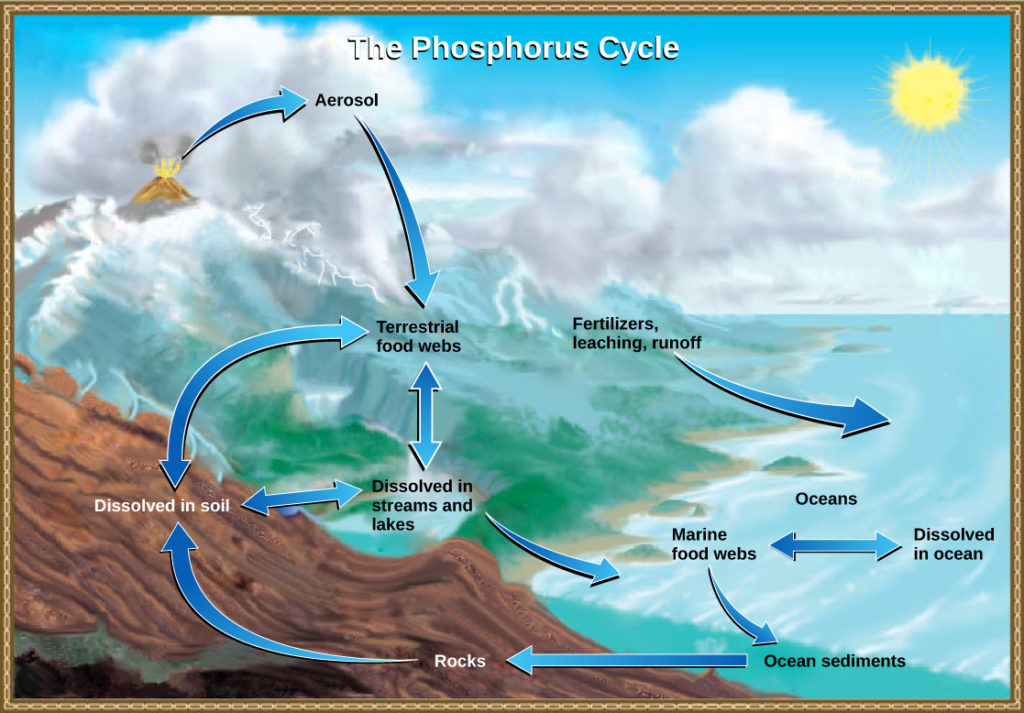

Phosphorus, a major component of nucleic acid (along with nitrogen), is an essential nutrient for living processes; it is also a major component of phospholipids, and, as calcium phosphate, makes up the supportive components of our bones. Phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient (necessary for growth) in aquatic ecosystems (Figure 1).

Phosphorus occurs in nature as the phosphate ion (PO43−). In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, in remote regions, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of areas of the Earth’s surface.

Phosphorus is also reciprocally exchanged between phosphate dissolved in the ocean and marine ecosystems. The movement of phosphate from the ocean to the land and through the soil is extremely slow, with the average phosphate ion having an oceanic residence time between 20,000 and 100,000 years.

Phosphorus is one of the main ingredients in artificial fertilizers used in agriculture and their associated environmental impacts on our surface water. Excess phosphorus and nitrogen that enters these ecosystems from fertilizer runoff and from sewage causes excessive growth of microorganisms and depletes the dissolved oxygen, which leads to the death of many ecosystem fauna, such as shellfish and finfish. This process is responsible for dead zones in lakes and at the mouths of many major rivers (Figure 2).

A dead zone is an area within a freshwater or marine ecosystem where large areas are depleted of their normal flora and fauna; these zones can be caused by eutrophication, oil spills, dumping of toxic chemicals, and other human activities. The number of dead zones has been increasing for several years, and more than 400 of these zones were present as of 2008. One of the worst dead zones is off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico, where fertilizer runoff from the Mississippi River basin has created a dead zone of over 8463 square miles. Phosphate and nitrate runoff from fertilizers also negatively affect several lake and bay ecosystems including the Chesapeake Bay in the eastern United States.

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay has long been valued as one of the most scenic areas on Earth; it is now in distress and is recognized as a declining ecosystem. In the 1970s, the Chesapeake Bay was one of the first ecosystems to have identified dead zones, which continue to kill many fish and bottom-dwelling species, such as clams, oysters, and worms. Several species have declined in the Chesapeake Bay due to surface water runoff containing excess nutrients from artificial fertilizer used on land. The source of the fertilizers (with high nitrogen and phosphate content) is not limited to agricultural practices. There are many nearby urban areas and more than 150 rivers and streams empty into the bay that are carrying fertilizer runoff from lawns and gardens. Thus, the decline of the Chesapeake Bay is a complex issue and requires the cooperation of industry, agriculture, and everyday homeowners.

Of particular interest to conservationists is the oyster population; it is estimated that more than 200,000 acres of oyster reefs existed in the bay in the 1700s, but that number has now declined to only 36,000 acres. Oyster harvesting was once a major industry for Chesapeake Bay, but it declined 88 percent between 1982 and 2007. This decline was due not only to fertilizer runoff and dead zones but also to overharvesting. Oysters require a certain minimum population density because they must be in close proximity to reproduce. Human activity has altered the oyster population and locations, greatly disrupting the ecosystem.

The restoration of the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay has been ongoing for several years with mixed success. Not only do many people find oysters good to eat, but they also clean up the bay. Oysters are filter feeders, and as they eat, they clean the water around them. In the 1700s, it was estimated that it took only a few days for the oyster population to filter the entire volume of the bay. Today, with changed water conditions, it is estimated that the present population would take nearly a year to do the same job.

Restoration efforts have been ongoing for several years by non-profit organizations, such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The restoration goal is to find a way to increase population density so the oysters can reproduce more efficiently. Many disease-resistant varieties (developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for the College of William and Mary) are now available and have been used in the construction of experimental oyster reefs. Efforts to clean and restore the bay by Virginia and Delaware have been hampered because much of the pollution entering the bay comes from other states, which stresses the need for inter-state cooperation to gain successful restoration.

The new, hearty oyster strains have also spawned a new and economically viable industry—oyster aquaculture—which not only supplies oysters for food and profit, but also has the added benefit of cleaning the bay.

Video Review

Many organisms require nitrogen and phosphorus. This video explains just how they go about getting them via the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles.