15 Marsh, “The Personal is Political: Gender in Private & Public Life in the 19th Century”

In the 19th century female skills were in demand outside the home. Throughout the Victorian period, when family needs allowed, women undertook unpaid work in a variety of fields, known collectively as philanthropy. Typically operating at local level, often through Church structures, these activities might today be classified as ‘social work’. They included distributing clothes, food and medicines; teaching literacy, home care and religion; and ‘parish visiting’ of the poor and infirm. As the century progressed, such roles were increasingly professionalised, through local and central government institutions, which in time offered recognised occupations for able women. Those who would once have stitched for a church bazaar or carried bowls of broth to starving widows began to train themselves seriously. One famous example is provided by Octavia Hill (1838-1912) who managed a slum-housing scheme, collecting rents, overseeing repairs and demanding cleanliness from tenants. Although her work was on a small-scale, she also trained and inspired others, including Lily Walker, Housing Manager for Dundee Social Union, and Ella Pycroft, of the London East End Dwelling Company.

Religion, too, offered rewarding work and a satisfactory social niche. From the late 1840s dedicated women were able – often against family pressure – to fulfil their vocation in Anglican orders engaged in devotional and philanthropic work, or as lay deaconesses. The Dissenting churches, with their earlier but now curtailed tradition of female preachers, also expanded laywomen’s role, especially in Sunday school teaching, while independent sects offered the stirring spectacle of women preaching publicly. The most notable of these was surely Catherine Booth, co-founder of the Salvation Army. Overseas mission work likewise required women’s labour – usually as wife to a missionary husband, but on occasion for a single woman like the redoubtable Dr Mary Slessor (1848-1915), who ran a renowned service in eastern Nigeria.

‘Good causes’ were also open to both sexes. British women were initiators and activists in campaigns to abolish slavery in the United States, to revoke the Contagious Diseases Acts at home and to promote teetotalism, to cite three of many reform movements for which they gathered petitions, organised meetings and lobbied politicians identified as a primary cause of poverty and violence. Alcohol abuse attracted campaigners from all social classes and regions. ‘The demon drink’ was castigated by the unlettered Scottish poet Janet Hamilton; the British Women’s Temperance Association was founded in Newcastle; and the Countess of Carlisle devoted her considerable energies to the cause. For many men, abstinence became a marker of virtue, but by the same token for others drink signalled the individual right to choose one’s own pleasures.

Throughout the period, daily life remained differentiated, despite changes in some customs. One small example demonstrates how in the 1830s and 1840s the habit of paying social calls still prevailed among the middle and upper classes, but as gentlemen increasingly took full-time work, by the 1870s and 1880s this practice had become largely feminised. Private letter writing, which hugely increased thanks to the penny post, was also a largely female task. While men customarily undertook business communication, social networking thus fell to women.

As numerous poems and paintings testify, mother love was central to ideas of family, but fathers were also allocated an increasingly affectionate role. As the ideal of companionate and complementary marriage flourished with the promotion of domestic harmony, so home life grew in significance for men, although from 1870 the attractions of home lost ground again to the ‘bachelor’ world of clubland and regiment. Moreover, even in kindly, liberal households, men were entitled to be looked after. ‘One thing I thoroughly enjoy’, wrote Christina Rossetti when her brother married in 1874, ‘[is] that my mother and I can now go about just as we please… without any consciousness of man resourceless or shirt-buttonless left in the lurch!’

In working-class homes, where there were often equal but different burdens of work, men were entitled to better food and more leisure. A major site of struggle focused on their right to spend money on themselves rather than family and household maintenance – expressed visually with the careworn wife and hungry children waiting forlornly outside the public house.

Economic and social pressures ensured that marriage remained the goal of women in all classes; statistics show that 85 per cent married by the age of 50, in a society that expected them to be the subservient partner. Custom and common law supported the age-old notion that men could command, while women should obey. Since personal ambition was a masculine virtue but a feminine vice, the highest female aspiration was to minister to a male genius – as the lives of Jane Carlyle and Emily Tennyson amply testify. Modesty, self-denial and sweet temper were the admired feminine qualities. The masculine ideal was self-control, the famous stiff upper lip of Empire and mastery over others.

Women in public spaces

Over the 70 years of Victoria’s reign, public spaces remained largely gendered. Whereas men of all ages and classes were free to go where they wished, in the town or countryside, many locations were ‘off-limits’ to unaccompanied women. At the end of the period as at the beginning, young ladies were obliged to have a chaperone – at least a servant – when out walking or attending an evening event. ‘When it was explained to me that a young girl by herself was liable to be insulted by men, I became incoherent with rage at a society which shut up the girls instead of the men’, recalled Helena Swanwick.

Habits varied and changed. By 1880 daytime shopping was a popular female activity, for example; nevertheless only men enjoyed free access to bars, music halls and most outdoor sports. Cycling was thought a bold activity for women, though genre painting suggests that the new game of tennis was enjoyed by both sexes. One marker of the end-of-century New Woman was greater independence, symbolised by her own door-key to the family home, so she might come and go as she pleased.

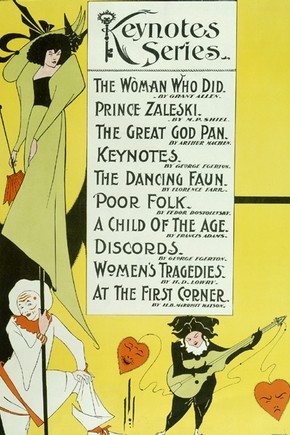

Although to some degree a ridiculed media creation similar to the ‘bra-burning Woman’s Libber’ of the 1970s, the New Woman – first identified by name in 1894 – emerged from widespread female discontent with marriage as currently constituted and signalled the arrival of a newly vocal generation. And however small, each step towards gender equality meant a diminution – sometimes barely visible – of male power and privilege. New women expected to travel and live independently, to earn their own living and to choose their own partners; they also paved the way for the militant Suffragettes of the 1900s.

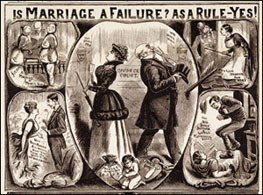

Those defending the status quo – who included a substantial number of women – argued that male duties to support families and to fight for their country were responsibilities, not privileges; and that British women possessed incomparable moral influence and power. Only in a few, ‘advanced’ circles was the ideal of equal partnership in earning, decision-making and domestic affairs discussed. Indeed, the vigorous humour directed against the dominant wife and her ‘henpecked’ husband indicates that equality aroused real fear of change.

In regard to equal legal and political rights, the century saw vigorous campaigns, if few gains. In 1854 A Brief Summary, in Plain Language, of the Most Important Laws concerning Women, was drawn up by the young Barbara Bodichon, a leading feminist of the age. This itemised the injustices of the legal system, including male rights to custody of children, to the wife’s income and property, and to sexual (‘conjugal’) pleasure at will. Married women were especially ill placed. As Mill observed, ‘marriage is only actual bondage known to [English] law. There remain no legal slaves except the mistress of every household.’ But spinsters and widows were also denied all rights to political representation, and by custom a younger brother or adult son was deemed senior male and ‘head of the household’.

At its worst, law and custom gave men the right to oppress female dependants, and to immure, beat and rape their wives. As Mill remarked, a husband might commit any atrocity against his wife short of killing her – ‘and if tolerably cautious, can do that without much danger of legal penalty’.

A changing legal environment

A brief summary of the most important legal changes shows how during the rest of the century some gender injustices were removed, although it was a slow process and only very partially achieved. Notable events included the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, and the 1891 Court of Appeal ruling that ‘when a wife refuses to live with her husband he is not entitled to keep her in confinement in order to enforce restitution of conjugal rights’. But there was no legislation on equal pay or opportunity, and numerous other inequities also remained.

In 1837, as Chartist demands demonstrated, the majority of men remained unenfranchised. Thanks to legislation in 1867 and 1884, by 1901 virtually all adult men enjoyed the vote. But despite a long and sustained campaign, headed by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies led by Millicent Fawcett, time and again women were expressly denied the right to take part in national elections.

‘Is Marriage a Failure?’, 1891. The British Library

Thus, at the close of Victoria’s reign, gender inequality remained a fact of British life, most clearly symbolised by exclusion from the parliamentary franchise. The demand voiced for 50 years therefore became a keynote for the new century: VOTES FOR WOMEN.

Jan Marsh

Jan Marsh is the author of The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood (1985) and biographies of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Christina Rossetti. She has written widely on gender and society in the 19th century. She is currently a visiting professor at the Humanities Research Centre of the University of Sussex and is working on Victorian representations of ethnicity.