100 Internet Resources

We want Google to be the third half of your brain. – Sergey Brin

Search Engines

A search engine can be your most important resource when attempting to locate information on the Internet. Search engines allow you to type in the topic you are interested in and narrow the possible results. Some of the most popular search engines include Google, bing, Yahoo!, and Ask.[1] These sites provide a box for you to type a topic, phrase, or question, and they use software to scan their index of existing Internet content to find the sites most relevant to your search.

Each search engine uses different algorithms and techniques to locate and rank information, which may mean that the same search will yield different results depending on the search engine. Based on the algorithms it is using, the search engine will sort the results with those it determines to be most relevant appearing first. Since each site is different, you should use the one that seems most intuitive to you. However, since their ranking systems will also be different, you cannot assume that the first few sites listed in your chosen search engine are the most relevant. Always scan the first few pages of search results to find the best resource for your topic. Skimming the content of the pages returned in your search will also give you an idea of whether you have chosen the most appropriate search terms. If your search has returned results that are not relevant to your speech, you may need to adjust your search terms and try a new search.

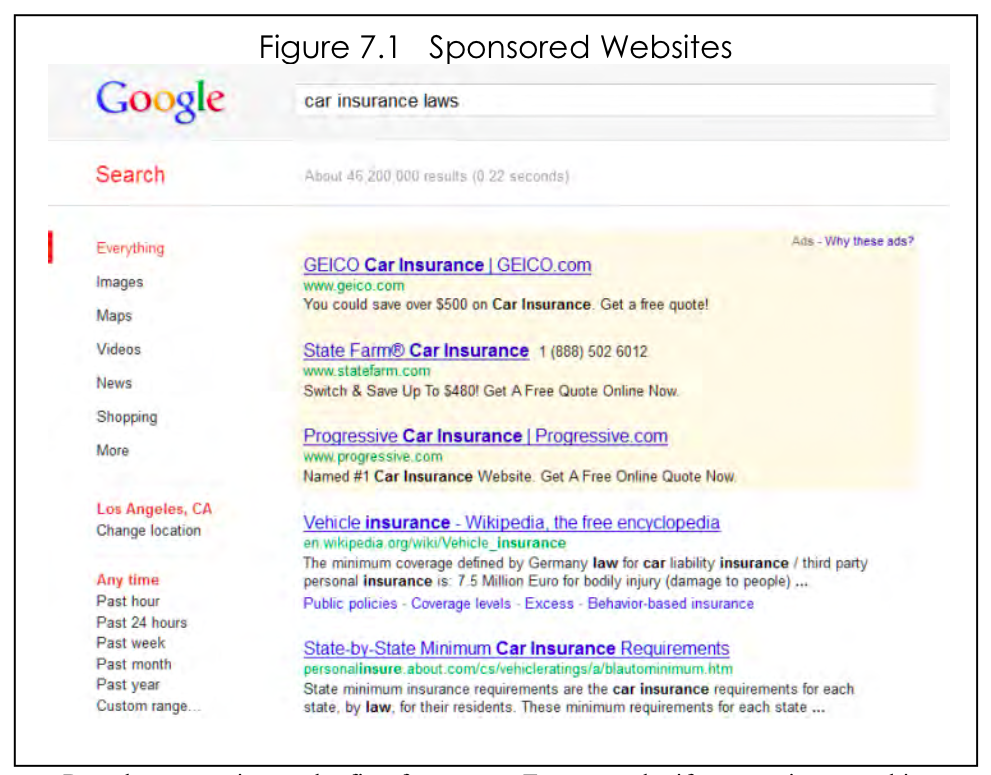

Pay close attention to the first few sites listed in search results. Some databases allow “sponsored links” to appear before the rest of the results. If you are giving a speech about the dangers of rental cars, and you search rental car in Google, links to companies like Hotwire.com, Orbitz.com, or National Rental Car are likely to appear first in your results. These sites may or may not be relevant to your search, but they have also paid for the top spot on the list and therefore may not be the most relevant. When search engines display sponsored sites first, they typically distinguish these from the others by outlining or highlighting them in a different color. For example, while Google lists advertisements related to your search on the right-hand side of the screen, they sometimes also put a limited number of sponsored links at the top of your search results list. The only distinction between these sponsored links and the rest of the list is a subtly shaded box with a small label in the upper right indicating they are “Ads” (see Figure 7.1).

Defining Search Terms

In the early stages of research it may be helpful to simply search by topic. For example, if you are interested in giving a speech about revolutions in the Middle East, you might type that topic into the database and scan the sites that come up. As you are scanning, watch for other useful terms that arise in relation to the topic and jot them down for possible use in later searches. Since people may write about the topic in different terms than you tend to think about it, paying close attention to their language will help you refine your search. Another way to approach this is to consider synonyms for your search terms before you even begin. Once you have a concrete topic and have begun to outline the arguments you want to make, you are likely to need more specific terms to find what you are looking for. In order to help with the search, you may use Boolean operators, words and symbols that illustrate the relationship between your search terms and help the search engine expand or limit your results (see Table 7.2 on the next page for examples). Although search engines regularly adjust their Boolean rules to avoid people rigging the site to show their own pages first, a few basic terms tend to be used by most search engines.[2]

| Table 7.2: Boolean Operators | |

|---|---|

| OR | The word “OR” is one way to expand your search by looking for a variety of terms that may help you support your topic. For example, in a speech about higher education, you might be interested in sources discussing either colleges or universities. In this case using the term “OR” helps expand your search to include both terms, even when they appear separately. |

| AND/+ | Using the word “AND” or the “+” symbol between terms limits your search by indicating to the search engine that you are interested in the relationship between the terms and want to see pages which offer both terms together. If you are giving a speech about Hillary Rodham Clinton’s work in the Senate, you might search Hilary Rodham Clinton AND Senate. This search would help you find information pertaining to her senate career rather than sites that focus on her as First Lady or Secretary of State. |

| NOT/- | Using the word “NOT” or the “-” symbol can also limit your search by indicating that you are not interested in a term that may often appear with your desired term. For example, if you are interested in hyenas, but want to limit out sites focused on their interactions with lions, you might search hyena -lion to eliminate all of the lion pages from your search. |

| “ ” | Quotation marks around a group of words limit the search by indicating you are looking for a specific phrase. For example, if you are looking for evidence that human behavior contributes to global warming, you might search “humans contribute to global warming,” which would limit the search far beyond the simple human + global warming by specifying the point you seek to make. |

When you have a well-defined area of research, it is best to start as specific as possible and then broaden your search as needed. If there is something on exactly what you want to say, you don’t want to miss it wading through a sea of articles on your general topic area. To make the best use of your search engine take some time to read the help section on the site and learn how their Boolean operators work. The help section will offer additional tips to assist you in navigating the nuances of that site and executing the best possible search.

You may be at least somewhat familiar with Google, the name that has become synonymous with “internet search,” and called “the most used and most popular search engine.”[3] You may already be adept at searching Google for a wide variety of information, but you may be less familiar with some of its specialized search engines. Three of these search engines can be particularly helpful to someone seeking to support their ideas in a speech: Google Scholar, Google Books, and Google Images.

Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose. – Zora Neale Hurston

Google Scholar

The search engines listed earlier in this chapter will help you explore a diversity of sites to find the information you are looking for. However, certain topics and certain types of speeches call for more rigorous research. This research is typically best found in the library, but Google has an added feature that makes finding scholarly sources easier. On Google Scholar you can find research that has been published in scholarly journal articles, books, theses, conference proceedings, and court opinions.

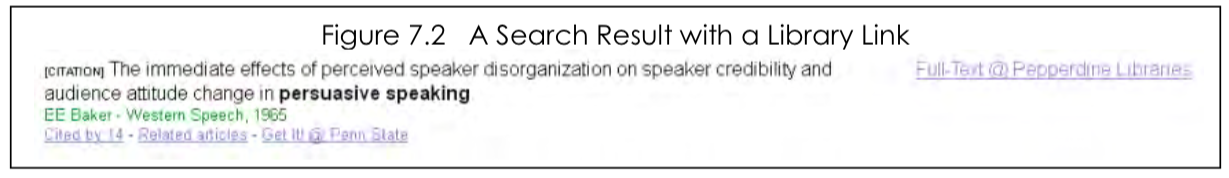

Google Scholar is not only helpful for focusing on academic research; it has a host of features that will help to refine your search to the most helpful articles. You can search generally in Google Scholar and find citations of useful articles that will help support your ideas, but you may not always find the full text of the article. You can ask Google Scholar to help you find the full text articles available in your library’s databases by telling it which library you want to search. To do this, click the “scholar preferences” link next to the search button on scholar.google.com. Then scroll down to the section titled “library links,” and type the name of your school or library, then click “find library.” When the search is complete, check the box next to the name of your library so that Google knows to include it in the search. Once you have included your library, the search results you get will have links that lead you to the articles available in your library’s databases (see Figure 7.2). Clicking the links will lead you to your library databases and prompt you to log into the system as you would if you were searching on the library site itself.

Even when you are linked to your library’s databases, there may be articles in your search results that you do not have electronic access to. In that case, search your library catalog for the title of the journal in which your desired article appears to see if they carry the journal in hard copy form. If you still cannot find it, copy the citation information and use your interlibrary loan system to request a copy of the article from another library.

I find I use the Internet more and more. It’s just an invaluable tool. I do most of my research on the Net now… – Nora Roberts

In addition to enhancing your database searches, Google Scholar can also help you broaden your search in two strategic ways. First, underneath the citation for each search result, you will see a link to “related articles.” If you found a particular article helpful, clicking “related articles” is one way to help you find resources that are similar. Second, as you know, researchers often look through the bibliography of a helpful source to find the articles that author used. However, when you are dealing with an older article, searching backwards in the bibliography may lead you to more outdated research. To search for more recent research, look again under the search result for the link called “cited by.” Clicking the “cited by” link will give you all of the articles that have been published since, and have referred to, the article that you found. For example, if you are giving a speech on male body image you might find Paul Rozin and April Fallon’s 1988 article in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology comparing opposite sex perceptions of weight helpful. However, it would be good to have more recent research. Clicking the “related articles” and “cited by” links would lead you to similar research published within the past few years.

Google Books

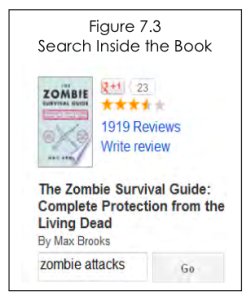

Just as Google Scholar can be used to enhance your research in scholarly periodicals, Google Books can be used to make your search for, and within, books more efficient. Some library catalogs offer you the ability to search for all books on a topic, whether that library has the book or not. Other libraries confine you to searching their holdings. One way to enhance your research is to search for books on Google Books and then use your library site to see if they currently have the book, or if you will need to order it through interlibrary loan. The other way that you can use Google Books is to make your skimming more effective. Earlier in this chapter you learned that you should strategically skim books for the information that you need. You can do that with Google Books by looking up the book, and then using the search bar on the left side of the screen (see Figure 7.3) to search for key words within the book. This search engine can help you identify the pages in a book where your terms appear and, with many books, give you a sample of that page to allow you to see whether the terms appear in the context you are searching for. Keep in mind that Google Books is a search engine; it is not a replacement for checking out the book in the library or buying your own copy. Google Books does not print books in their entirety, and often will omit pages surrounding a search result, so relying on the site to allow you to read enough of the book to make your argument is risky at best. Instead, use this site to help you determine which books to obtain, and which parts of those books will be most relevant to your research.

Google Images

Google Images may be useful as you seek visual aids to illustrate your point. You can search Google Images for photographs, charts, illustrations, clip art and more. For example, if you are giving a speech on the Nineteenth Amendment, you could add interest by offering a picture of the Silent Sentinel’s picketing the White House. Alternatively, if you wanted to demonstrate the statistical probability of electing a woman to Congress, you could use Google Images to locate a chart displaying that information.

Since search engines match the terms you put in, it is possible that your topic could yield images containing adult content. To prevent receiving adult content, you can use the “safe search” settings (located in the option wheel in the far upper right hand corner of the menu bar) to limit your exposure to explicit images. The setting has three options:

- Strict filtering: filters sexually explicit video and images from Google Search result pages, as well as results that might link to explicit content.

- Moderate filtering: excludes sexually explicit video and images from Google Search result pages, but does not filter results that might link to explicit content. This is the default SafeSearch setting.

- No filtering: as you’ve probably figured out, turns off SafeSearch filtering completely.[4]

Remember that, as with other outside sources, you will need to offer proper source citations for every image that you use. Additionally, if you plan to post your speech to the internet or publish it more widely than your class, consider using only images that appear in the public domain so that you do not risk infringing on an artist’s copyright privileges.

It is not ignorance but knowledge which is the mother of wonder. – Joseph Wood Krutch

Websites

When you use a more general search engine, such as Google or bing, you are looking for websites. Websites may be maintained by individuals, organizations, companies, or governments. These sites generally consist of a homepage, that gives an overview of the site and its purpose. From the homepage there are links to various types of information on the original site and elsewhere on the Internet. These sets of links arrange information “in an unconstrained web- like way,”[5] which opens up the possibility of making new connections between ideas and research. It also opens up the possibility of getting lost among all of the available sources. To keep your research on track, be sure to continue asking yourself if the sources you have found support your specific purpose statement.

Most websites are created to promote the interests of their owner, so it is very important that you check to see whose website you are looking at. Generally the author or owner of the site is named near the top of the homepage, or in the copyright notice at the bottom. Knowing who the site belongs to will help you determine the quality of the information it offers. If you find the site through a search engine and are not directed to its homepage, look for a link called “home” or “about” to navigate to the page containing more information about the site itself. In addition to knowing the owner, it is important to look for the author of the material you are using. For example, an article on a reputable news site like CNN.com may come from a respected journalist, or it may be the opinion of a blogger whose post is not necessarily vetted by the company itself. Use the section of the chapter on evaluating information to determine whether the site you have found is a credible source.

When you find websites that are both useful and credible, be sure to bookmark them in your Web browser so that you can refer to them again later. Your browser may call these bookmarks “favorites” instead. To bookmark a site, you can click on the bookmarking link in your browser or, if your browser uses tabs, you can drag the tab into a toolbar near the top of the window. If you are struggling with the bookmarking process, try the command CTRL+D on your keyboard or consult the help link for your Web browser.

Don’t leave inferences to be drawn when evidence can be presented. – Richard Wright

Government Documents

Governments regularly publish large quantities of information regarding their citizens, such as census data, health reports, and crime statistics. They also compile transcripts of legislative proceedings, hearings, and speeches. Most college and university libraries maintain substantial collections of government documents. Additionally, these documents are increasingly available online. Government documents can be helpful for finding up-to-date statistics on an issue that affects the larger population. They can also be helpful in identifying strong viewpoints concerning government policies. For example, looking at the Congressional testimony regarding nuclear safety after an earthquake destroyed the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan in 2011 could help you make a compelling case for safety upgrades at U.S. nuclear power facilities.

Now, whenever you read any historical document, you always evaluate it in light of the historical context. – Josh McDowell

One of the most helpful resources for searching government documents is http://fedworld.ntis.gov/. This site allows you to search Supreme Court decisions, government scientific reports, research and development reports, and other databases filled with cutting edge research. It also lists all major government agencies and their websites. Another excellent way to locate government documents is to use the Monthly Catalog of U.S. Government Publications. This index is issued every month and lists all of the documents published by the federal government, except those that are restricted or confidential. You can use the index to locate documents from Congress, the courts, or even the president. The index arranges reports alphabetically by the name of the issuing agency. The easiest way to search will be on the Government Printing Office website at catalog.gpo.gov. If you would prefer to work with hard copies of the reports, head to your library and search the subject index to find subjects related to your speech topic. Each subject will have a list of documents and their entry number. Use the entry numbers to find the title, agency, and call number of each document listed in the front of the index.[6]

- eBizMBA. (2012). Top 15 Most Popular Search Engines: January 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/search-engines ↵

- BBC. (2012). What are “Boolean operators?” WebWise: A Beginner’s Guide to Using the Internet. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/webwise/0/22562913 ↵

- Tajane, T. (2011). Most used search engines and total market share trend as of March 2011. TechZoom.org. Retrieved from: http://techzoom.org/most-used-search-engines-and-total-market-share-trend-as-of-march-2011/ ↵

- Google. (2012). SafeSearch: filter objectionable content. Google Inside Search. Retrieved from: https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/510?hl=en ↵

- Berners-Lee, T. & Fischeti, M. (2000). Weaving the web: The original design and ultimate destiny of the World Wide Web. New York, NY.: Harper Collins. ↵

- Zarefsky, D. (2005). Public Speaking: Strategies for Success (Special Ed. for The Pennsylvania State University). Boston, MA: Pearson. ↵