13 12. Communication, Stress and Conflict

Learning Outcomes

At the end of this chapter you will be able to do the following.

Define types of arguments

Distinguish between needs and wants

Relate how to improve communication

Apply the Leukemia of Arguments metaphor

Define marital entropy

Define mood and affect

Analyze how power is maintained

“You did.” “No, I didn’t.” “Yes, you did.”

“No, if you remember it was you.” “Humm, you may be right.”

“I told you so!” “No, you didn’t.” “Yes, I did…”

ARGUMENTS

So often arguments focus on who was right, which facts were involved, and ultimately who is to blame. These types of arguments are annoying both to have and to overhear. These are called non-directional arguments, because the underlying issue is not being dealt with in the argument itself. Non-directional arguments happen for many reasons, but rarely help resolve an issue. Arguing is a quandary for many people because they believe that arguing is a weakness, sign of trouble, or even a sin. Marriage and family researchers have established for years that it is not the argument that is the problem; it is how the argument transpires that matters.

Directional arguments have a goal or a purpose and usually approach the issue that led to the argument in the first place. It isn’t always obvious how to argue in such a way that it accomplishes something useful. Markman et al. (2001) have established a training program for how to help couples fight for their marriages.1 Likewise, John Gottman (2002) published a relationship book that focuses on strategies for healthy arguments (among other strategies).2 The core of a healthy argument is to get to the root of the problem in such a way that both parties can be content with the outcomes. Easier said than done? Learning to argue is not rocket science. Have you ever heard the phrase “beat around the bush?” In Figure 1 the bush is the argument. The real source of the argument comes from the roots or core issue. So often when we argue about who was right and who is to blame, or when we become emotional and react to what the other says, we waste time beating around the bush rather than getting to the real issue.

The root cause is often less obvious because we don’t always know exactly what is bugging us. We simply get frustrated or concerned and start talking. If emotions and pride set in, the argument becomes non-directional and burdensome.

Figure 1. Getting to the Core of the Problem: The Roots.

The diagram in Figure 2 shows the same principle found in Figure 1. In Figure 2 the core of the problem lies on the left side of the “root of most disagreements” and these core issues are common for most people. Our values are what we define as important, desirable, and of merit. Our beliefs are what we define as real and accept as truths in our lives. Needs are those things that are necessary to our existence and wants are those things we would like to have. Our values, beliefs, needs, and wants are typically where most core issues originate.

Let’s walk through the model with a case study. A young couple married and were saving to eventually make a down payment on a home. She worked in the loan department of a bank and he worked in construction. One Friday afternoon she came home from work. She had a difficult day at work and was especially tired and stressed. She opened the door to their apartment, carrying a box of paperwork in her arms. Not knowing her husband had taken off his muddy work boots, she tripped and almost fell. She sat her box down and looked down only to find that her best work shoes had mud on them and were now scratched. She slipped them off thinking she would have to come back later and clean them up. On the way to the bedroom she tipped over a half-eaten bowl of cereal that dampened her sock and messed up the carpet. She made it to the bedroom and dropped the box on the floor. She took off her socks and put them on the bathroom sink. She then noticed her husband’s muddy pants draped over the toilet. She suddenly realized that within less than one minute, she now had to clean, her muddy shoes, her sticky socks, the wet carpet, and the toilet. Just then her husband returned from the mailbox and said “Honey, I’m home.”

Figure 2. How to Have a Healthy Argument: The Win-Win Model.

Her husband had arrived 30 minutes earlier excited about a pay raise he’d received that day. He had showered, started eating a bowl of cereal, and darted out to get the mail. When he walked in the door she slammed the bedroom door and locked it. “Honey are you in there?” he asked knocking on the door. “Leave me alone!” she yelled through the door while crying. “Honey what’s the matter; are you okay?”

“I’m fine!”

“Did I do something wrong?” “No, I did when I married a pig!”

“A pig?”

“Yes, you live like a pig!”

“Well, well whose mother is always meddling in our marriage?”

“What?” She gasped. “Then whose uncle is in prison for life!”

“That’s it.” He stomped out of the apartment and drove off.

This is a non-directional, beating around the bush, and hurtful argument. You can see what happened to them using the diagram in Figure 2. Somewhere between the muddy boots and the toilet, she felt a perceived injustice. She felt like her husband did not respect her need to keep a clean apartment. Her emotional response was anger. It happens to us all, but in this case it wasn’t controlled very well and she took the low-road in this diagram which is the combat response. When she slammed the door and called him a pig, she was attacking him, emotionally, psychologically, and or intellectually. By doing this she inadvertently gave him a perceived injustice. He also has values and most likely felt that his need to be respected by his wife was not met. He perceived an injustice of maltreatment, felt hurt, then also took the low road and retaliated with an attack on her mother. Had this argument continued, the vicious cycle of beating around the bush or perpetually providing each partner with a perceived injustice, emotional response, and combat opportunity may have continued. Notice that the core issues were never dealt with in their communication. Never in this exchange did either of them get to their needs, wants, values, or beliefs. She came from a home where her mother was an immaculate homemaker, stay-at-home mother, and artist. She and her mother prided themselves on the cleanliness and order of their homes. She married a young man whose mother cleaned up after him. He could count on one hand the number of times he cleaned his room while growing up. They chose each other! On top of that she was stressed and tired and he was jubilant from the good week at work and pay raise. Neither is to blame. Arguments happen to everyone and unhealthy ones will be the pattern unless they do something about it. They both had to modify their behaviors so that they could get to the core issues and support one another. To do that, they’d have to take the high road.

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION

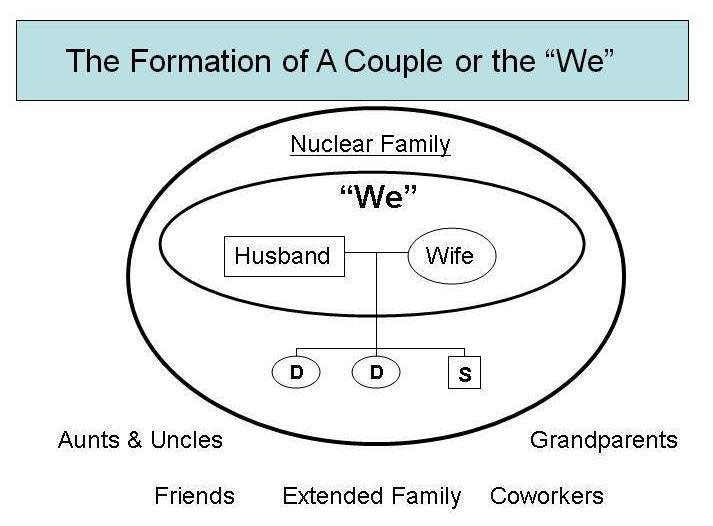

The high road in this model offers problem resolution strategies which have been around the counseling and communications literature for many years. They’ve been researched and discussed in numerous self-help and consulting books over the last two decades. They work well and offer techniques which facilitate a healthy argument and outcome. The first strategy is to negotiate a win-win solution. The goal is that everyone can find a way to work out an argument or disagreement so that the other person feels like he or she came out with his or her needs addressed and met as well. Think about it, if you always win then your partner always loses. That would make her or him a loser and who wants to be married to a loser? Figure 3 shows the diagram of how a couple forms an entity called the “We.”

A couple is simply a pair of people who identify themselves in terms of belonging together, trusting one another, and having a unique relationship, separate from all others. A “We” is close to the same thing, yet it focuses on the relationship as an entity in itself. A “We” as shown in this diagram is a married couple but can include cohabiters, or other intimate non-married couple arrangements. This is a relationship that is not intimately connected to any other relationships as profoundly as they are connected to one another. A “We” is much like a vehicle that two people purchase together. Both have to put in maintenance. Both have to care for it and treat it in such a way that it runs for a long time. Sometimes, spouses or partners attack the other in such a way that the other is harmed or damaged in their trust. A “We” is the social and emotional boundary a couple establishes when they decide to become a couple. This boundary includes only the husband and wife. It purposefully excludes the children, extended family, co-workers, and friends.

When one spouse is made to feel like the loser, then it’s like getting upset and scratching the car’s paint or stabbing a tire with a screwdriver. How long can a car last if one inflicts damage in this way? The key is to remember that together you have formed a social bond that can only be as strong as its weakest part. Many non-directional arguments weaken one or both partners and can lead to an eventual abandonment of the relationship since this undermines the emotional connection and bond.

Figure 3. How the Couple Forms a “We”

Knowing a strategy to create a win-win situation makes it much more likely to happen. Think about what you might need if you were the couple in the story above. What might she desire? Perhaps she’d like for him not to make messes for her. What might he desire? Perhaps he’d like for her to refrain from calling him farm animal names. So, later, after both have cooled down they may decide to talk about what happened and forgive one another. Then, they might try to answer this key question, each taking a turn to listen to the other, “What was really at the core of your concern?”

“Well, I’ve talked to you for nearly two years about how hard it is for me to feel love for you when I pick up after you and clean up your messes,” She might say.

“Well, I’ve heard you and your family members call people names when they are not present, and I need for you to refrain from calling me names like that,” He might say.

Then they can answer this healthy, pro-couple, and mutually nurturing question, “What can we agree upon to help us meet each other’s needs better so we can avoid arguments like this in the future?” What might be your suggestion to them in answer to that question? Keeping in mind that it is very difficult for humans to change their natures. It is much easier for humans to change one very specific unwanted behavior. Knowing that, you could urge them to consider working together as a team with a reward at the end of a designated period of time. They might agree that she will not call him any farm animal names for 90 days. He in turn will make sure that his muddy boots are not in her path for 90 days. If they both live up to their end of the bargain, they might reward themselves with a weekend away together. This would not only be a win-win, but it would be realistically attainable for a young couple. It also avoids damaging the “We” while supporting it in the long run because it deals with their root core issues.

Now, some of you may feel frustrated that she didn’t negotiate a completely mess-free home. I’d argue that it’s much easier to change when the individual himself is motivated to make the change, not his spouse and working on one specific behavior is much more likely to produce lasting change. It’s also a fact that we choose who we marry or pair off with and they are who they are. In most relationships it’s unfair to say to a spouse or partner that “I love you just the way you are, so let’s get married.” Then later turn around and say. “I loved you the way I thought you were, but could you please change that to what I now think I want you to be?”

If we don’t want to change we won’t. It also gets more difficult to change the older we get. Most of us don’t want to change ourselves, especially in dramatic ways. If for whatever reason you decide to change a behavior, keep in mind these three levels of recognizing where you may be on the path to change. Let’s say you wanted to stop getting angry while driving your car on the freeway. So, you set a goal to go one month without using profanities while driving. Sure enough after a long day and busy afternoon rush hour you slip up and let the words fly. This is the first level of personal behavior change, when you catch yourself after the fact. In other words, you did it again and realized it too late.

But, you don’t give up on your goal. Next week after a long day and in the middle of a jam up of stopped traffic you start with the profanities but catch yourself mid-sentence and control your language. The second level of change is catching yourself in the middle of the act of the behavior you are trying to change. The third level is when you finally recognize which triggers set off this pattern of profanity for you. You realize that you curse more after stressful days at work and during traffic jams that slow your speed while traveling to the day care to pick up your child.

At the third level you can prepare how you will manage the stressors and thus prevent another slip up. Perhaps you might put the radio on to easy listening, decide that being late back home is acceptable even if it costs a few more dollars for day care, and or put in a self-help tape to listen to during the delay. Either way, we can change our own behaviors if we are persistent and patient. But, rarely can we change the behaviors of others.

The second option under Figure 2, Problem Resolution Strategies is to Agree as a Gift. This is to be done only on very unique circumstances. Agreeing as a gift means that you are willing to give in on something of importance at your root level. Let’s use the example of a couple who were building their own home. They were exhausted and burned out. One day during a normal morning start to the day. He mentioned that in the day’s schedule he wanted to go down to the brick yard and pick out the brick. He’d assumed that brick would be the best way to go. She brought up the point that she had already mentioned using stone instead of brick to him months before and had already picked out three types she really liked. They ended up in a heated argument. The next day he expressed his sorrow for assuming that she would just go with him on the brick idea. He then offered her this olive leaf, “I’ll support whatever stone you think is best for the outside of our new home.” She was surprised and asked him why he’d give in like that. “You spend more time at home with the children. You grew up in a home faced with stone, and to me, I just was trying to be efficient about getting this home built and it really didn’t matter for me as much as it does for you.”

They both then talked about how tired and worn out they had become and how dangerous building a home can be to a marital relationship. In this case, he offered to agree as a gift. It wasn’t a negotiation for future authority to decide on a home trait. It was an unattached gift. It’s important not to give in all the time; a one-sided relationship is not satisfying for either person in the long run. Martyrs always give in and find themselves unhappy with the direction of the relationship. The “We” is strong because of many negotiations which ensure that both parties can have their core issues addressed while meeting the needs of the other. If you sense the issue is more important to your partner than it is to you, give in.

Problem Resolution Strategy three is to simply learn to live with differences in a relationship. Most couples do have irreconcilable differences in their marriage or relationship. Most couples realize that each is an individual and each has uniqueness that they bring to the “We” which makes it what it is in terms of richness and viability. Some people think that their partner should change because their happiness may depend upon it. Many studies suggest that individuals are as happy as they choose to be, regardless of the changing that does or does not transpire in their relationship. Happiness is a conscious choice and exists when the individual persists in feeling happy even in difficult circumstances.3

Finally, Problem Resolution Strategy four is to simply change yourself. If you came from a home where a clean home reflected upon your self-worth, where a clean home meant a happy home, and where a clean home meant that you and your mother were close, and then you married a guy who never did housework, why should he have to change? He might over the years learn to share the housework responsibilities, but in the reality of things it might be easier to redefine the meaning of a clean home to yourself than to ask another individual to be something else in an attempt to accommodate your current tastes.

The model in Figure 2 is a useful way of understanding where arguments come from and how they might be best managed in such a way that the “We” is ultimately nurtured because the root issues are addressed by one another. One last suggestion in having a healthy argument, remember that not all issues are created equally.

Some arguments originate from a disease level in one of the partner’s personality—the Leukemia of arguments. They stem from an underlying medical condition that requires professional intervention. Many personality disorders might lead a couple to professional counseling and can undermine the “We” if not treated professionally. Just like Leukemia, if professional help is not sought, the relationship will suffer and might die.

Then there are the day-to-day arguments that are very common during the first three years. How to squeeze the tooth paste tube, how to cook an omelet, and how to drive to a destination are common issues of these arguments, especially among newlyweds. These arguments can be useful in the sense that they give the couple practice in having healthy arguments. Peaceful resolution of these minor arguments are a training ground for resolving major arguments.

Practice is important because major arguments threaten the very life of the relationship if unchecked. These occur when the very core values, beliefs, needs, and wants of a spouse are at stake. For example, the belief that marital sexuality should be exclusive to the couple is a deeply held belief that most couples respect. But when an extramarital affair does occur, the “We” has been damaged and it takes a tremendous amount of concerted effort to repair trust.

When arguing, first focus on the issues at hand and how to create a win-win outcome.

Second, don’t let others into the boundaries of your “We.” An argument should be between the partners, not the aunts, uncles, parents, children, or friends. Third, let professionals give you some training on how to argue in healthier ways. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when thousands of studies have been published on relationships. Self-help books and seminars can be very useful. And fourth, treat your relationship the same way you’d treat a nice car. Care for it, perform preventative maintenance, and avoid the tendency to ignore it, neglect it, or damage it.

Family Scientists have borrowed from the physics literature a concept called entropy which is roughly defined as the principle that matter tends to decay and reduce toward its simplest parts. For example, a new car if parked in a field and ignored would eventually decay and rot. A planted garden if left unmaintained would be overrun with weeds, pests, and yield low if any crop. Marital Entropy is the principle that if a marriage does not receive preventive maintenance and upgrades it will move towards decay and break down.

Couples who realize that marriage is not constant bliss and that it often requires much work experience more stability and strength than those who do not nurture their marriage. Those who treat their marriage like a nice car and become committed to preventing breakdowns rather than waiting to repair them reap the benefits. These couples read and study experts like Gottman, Cherlin, Markman, Popenoe, and others who have focused their research on how to care for the marriage, acknowledging the propensity relationships have to decay if unattended.

There are some basic principles that apply to communication with others. It is very important to know what you feel, and say what you mean to say. It sounds simple but people are not always connected to their inner issues. Our issues lie deep within us. Often we just see the tip of them like we might only see the tip of an ice berg. Some of us are strangers to them while others are very aware of what the issues are. When an argument arises, you might ask yourself these self-awareness questions. How did it happen, what lead up to it, and what was at stake for you? This helps many to get to the underlying issue.

Not only is it difficult for some of us to know what our issues are, but many of us have had relationships end painfully or with hurt feelings. These past hurts may inhibit open communication in current relationships. Figure 4 shows some of the painful arrows that threaten communication and trust. Some of us grow up feeling shamed and worthless. This sometimes makes us feel extremely sensitive to how others evaluate us and can make it very difficult for us to want to open up and show others what we believe are our flaws.

Figure 4. Inhibitions to Open Communication and Trust.

NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

Another crucial part of communication is the ability to communicate at the non-verbal level. Both non-verbal and verbal communication is essential for truly understanding one another. Non-verbal communication includes touch, gestures, facial expression, eye contact, distance, and overall body positioning. Touch is an essential part of the human experience. For the most part, women are very clear on which types of touch they give and receive. Women have cultural permission to be more affectionate with one another in the U.S. Men typically refrain from touching other men in heterosexual contexts (except in sports). Men touch women more than other men. Interestingly, comparing male to female newborns, most males enjoy their mothers’ physical closeness while the females enjoy the social interactions. Men have difficulties in distinguishing the varieties of touch and their intended purposes.

Gestures vary between cultures. You’ve heard the phrase “talking with your hands.” This is common in various parts of the U.S. among hearing individuals. Hands are moved in conjunction with words to emphasize and illustrate the point being shared. Deaf persons also communicate with a common form of non-verbal language called American Sign Language. Many parents teach ASL to their smaller children because toddlers can learn signs long before they can verbally articulate words. Gestures reinforce verbal messages and can be very useful in understanding a person’s intended message.

Eye contact is an extremely important aspect of communication. Making eye contact is difficult for some because the eyes truly do tell on the state of one’s emotions. The most common form of faking eye contact is the eye brow or forehead stare. Men are especially guilty of this because they are trying to communicate and as Deborah Tannen pointed out also trying not to be vulnerable.4

The average person in main stream U.S. society needs about 30-36 inches of space between him or her and another person. Strangers keep this distance where possible. Intimates close the gap to the point where they are very close side-by-side, touching at the hip, legs, etc. When people argue they often increase the distance. When people are being formally introduced to another they often maintain it. We not only want about three feet distance between us and others, we also want people to stay about that far away from our desk, doors, and even vehicles. This is in part why elevators are so uncomfortable; they don’t easily give us our three feet of space. Closing that distance with a stranger can be viewed as an act of aggression.

Finally, body positioning can be very insightful to a person’s disposition. You’ve probably already heard about the body positions that close other people out. There is the folding of the arms across the chest, the crossing of one’s legs, and the turning oneself around offering the back rather than the front to another person.

Therapists use verbals and non-verbals to assess both mood and affect. Mood is one’s state of emotional being and is typically detected by the words and patterns of speaking a person uses. Affect is one’s emotion or current feeling and is judged by a person’s non-verbal messages.

AVOIDING COMMUNICATION

All of us have vulnerabilities in our lives. We tend to cover them up and hide them for fear of them being exposed. Interestingly, when we find that when we get to know someone we really care about and they accept our vulnerabilities, it is a sign of love that often supports a decision to pair off together. Some people don’t ever want to experience conflict.

Conflict avoidant people tend to work extra hard to avoid conflict with others and often sacrifice the needed attention to issues that is required for a relationship to last. Conflict avoidant people rarely complain and some live like this forever while others experience a buildup of feelings and are very unhappy.

Each of us has painful experiences that are difficult to deal with. Sometimes we suppress them and bury them in the back of our mind. Sometimes we deny they even occurred. Sometimes we take these issues from our past and lay them onto our current relationships or project them onto our current partner. In all cases, the root core issue is difficult to access, yet still plays an important role in our daily interactions. Fear is very destructive to relationships. Fear is like a loud speaker of an emotion that can drown out reason and other emotions that pertain to our relationships. It is easy to respond to and often hard to understand.

Fear is like a super hot pepper. Our other emotions are more subtle like a grape. It is very difficult to taste a grape while simultaneously chewing on a hot pepper. Fears come from past hurts and pains. Rarely do they guide us in rationally effective ways. It’s estimated that 90% of what we fear never happens. If the ten percent does occur most of us can turn to others for support and get through it. Fear can shut open communication completely off and if we can manage our fears they will not manage us.

There are gender differences in how we communicate. Figure 5 shows a comparison of a psychologist’s and a sociologist’s take on gender differences in communication. Gray puts our genetic biological traits which stem from XX or XY at the core of why we talk and converse the way we do. He claims that we are built from the molecule up to be a predictable type of communicator. Many in his field criticize his conclusions and especially his claim that men and women may be a different species from one another.

Tannen talks about how we are socialized or raised by those around us. To her it’s about what we learn to expect from ourselves in the role of males or females that shapes how we communicate. The research she presents allows us to see how men are raised aware of their place in society. They are constantly aware that someone around them is bigger, stronger, faster, richer, etc. They know their place and work hard not to have someone of higher status put them down. Tannen claims that this approach to relationships—avoiding being put down and being very aware of status issues —is why many men refrain from opening up in conversation. Opening up puts them at risk of being put down.

To Tannen, women are raised in the context of relationships. They spend much of their lives reinforcing and strengthening relationships with friends and family. They are aware that informal rules guide their relationships and they put a great deal of effort into how to maintain good relationships so that they don’t find themselves socially isolated from others. This is why women tend to maintain more relationships than men and why men and women struggle to connect. Women approach the conversation with an effort to connect and maintain the relationship while men approach it trying to gain status or not be put at risk.

The real value of any gender self-help communication book is not that it identifies what all women or all men will say—that never happens because there is no generalized pattern of communication that all men or women fit into. The ultimate value of self-help gender communication books is to expand your understanding enough to see that your spouse or friend may simply be different from you and not wrong, mean, or uncooperative.

John Gray Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus (2004) vs. Deborah Tannen You just don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (2001)

Figure 5. Comparison of Two Gender Communication Self-Help Paradigms.

|

|

|

Gray-Psychologist |

Tannen-Sociologist |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Men |

One-sided brain users who hunt |

Raised to compete and be independent |

|

|

|

|

|

Strong emotional people who |

Status seekers who protect themselves |

|

|

|

|

|

solve problems alone |

from being put down |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Women |

Two-sided brain users who nuture |

Raised to connect to others while |

|

|

|

|

|

Feeling people who solve |

minimizing differences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

problems with others (in groups) |

Seek consensus while avoiding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

appearance of being superior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

POWER

When two people communicate they share a certain degree of power during the conversation. The Conflict Theory tells us that power is more often than not distributed unevenly. When we carry on conversations we sometimes find ourselves having more or less power in the conversation. The principle of least interest simply states that the partner who is least interested has the most power. In other words if you really want the relationship to work more than the other person, you have less power. If the other person wants the relationship to work more than you do, then you have more power. When relationships form, power changes hands from time to time depending on the nuances of the day-to-day interactions of the couple. Typically, women assume more responsibility for relationship maintenance in heterosexual couple’s interactions.

- Fighting for Your Marriage: Positive Steps for Preventing Divorce and Preserving a Lasting Love by Howard J. Markman, Scott M. Stanley, Susan L. Blumberg

- The Relationship Cure: A 5 Step Guide to Strengthening Your Marriage, Family, and Friendships by John Gottman.

- Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl

- You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation by Deborah Tannen