120 Changes to Iron Production

25.4.2: Changes to Iron Production

Technological advancements in metallurgy, most notably smelting with coal or coke, increased the supply and decreased the price of iron, aiding a number of industries and making iron common in the rapidly growing machinery and engine sectors.

Learning Objective

Break down how iron production changed during the Industrial Revolution

Key Points

- Early iron smelting used charcoal as both the heat source and the reducing agent. By the 18th century, the availability of wood for making charcoal limited the expansion of iron production, so England became increasingly dependent on imports from Sweden and Russia. Smelting with coal (or its derivative coke) was a long-sought objective, with some early advancements ٞachieved throughout the 17th century. Britain’s demand for iron and steel, combined with ample capital and energetic entrepreneurs, rapidly made it the world leader of metallurgy.

- A major change in the metal industries during the era of the Industrial Revolution was the replacement of wood and other bio-fuels with coal. Use of coal in smelting started somewhat before the Industrial Revolution, based on innovations by Sir Clement Clerke and others from 1678, using coal reverberatory furnaces known as cupolas. With cupolas, impurities in the coal did not migrate into the metal.

- Abraham Darby made great strides using coke to fuel his blast furnaces at Coalbrookdale in 1709. However, coke pig iron was hardly used to produce wrought iron in forges until the mid-1750s, when his son Abraham Darby II built Horsehay and Ketley furnaces. Since cast iron was becoming cheaper and more plentiful, it became a structural material following the building of the innovative Iron Bridge in 1778 by Abraham Darby III.

- Wrought iron for smiths to forge into consumer goods was still made in finery forges, as it long had been. However, new processes were adopted in the ensuing years. The first is referred to today as potting and stamping, but this was superseded by Henry Cort’s puddling process. Cort developed two significant iron manufacturing processes: rolling in 1783 and puddling in 1784. Rolling replaced hammering for consolidating wrought iron and expelling some of the dross. Rolling was 15 times faster than hammering with a trip hammer.

- Hot blast, patented by James Beaumont Neilson in 1828, was the most important development of the 19th century for saving energy in making pig iron. By using waste exhaust heat to preheat combustion air, the amount of fuel to make a unit of pig iron was reduced.

- The supply of cheaper iron aided a number of industries. The development of machine tools allowed better working of iron, increasing its use in the rapidly growing machinery and engine industries. Prices of many goods decreased, making them more available and common.

Key Terms

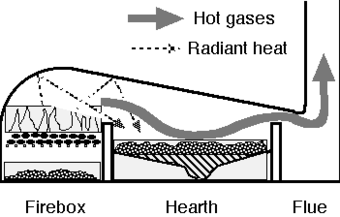

- reverberatory furnaces

- A metallurgical or process furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term reverberation is used here in a generic sense of rebounding or reflecting, not in the acoustic sense of echoing.

- Iron Bridge

- A bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first arch bridge in the world to be made of cast iron and was greatly celebrated after construction.

- pig iron

- An intermediate product of the iron industry. It has a very high carbon content, typically 3.5–4.5%, along with silica and other constituents of dross, which makes it very brittle and not useful as a material except in limited applications. It is made by smelting iron ore into a transportable ingot of impure high carbon-content iron as an ingredient for further processing steps. It is the molten iron from the blast furnace, a large cylinder-shaped furnace charged with iron ore, coke, and limestone.

- coke

- A fuel with few impurities and a high carbon content, usually made from coal. It is the solid carbonaceous material derived from destructive distillation of low-ash, low-sulfur bituminous coal. While it can be formed naturally, the commonly used form is man-made.

Iron and Industrial Revolution in Britain

Early iron smelting used charcoal as both the heat source and the reducing agent. By the 18th century, the availability of wood for making charcoal had limited the expansion of iron production, so England became increasingly dependent on Sweden (from the mid-17th century) and then from about 1725 on Russia for the iron required for industry. Smelting with coal (or its derivative coke) was a long-sought objective. The production of pig iron with coke was probably achieved by Dud Dudley in the 1620s, and with a mixed fuel made from coal and wood again in the 1670s. However this was only a technological rather than a commercial success. Shadrach Fox may have smelted iron with coke at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire in the 1690s, but only to make cannonballs and other cast iron products such as shells. In the time of peace, they did not enjoy much demand.

Britain’s demand for iron and steel, combined with ample capital and energetic entrepreneurs, rapidly made it the world leader of the metallurgy. In 1875, Britain accounted for 47% of world production of pig iron and almost 40% of steel. Forty percent of British output was exported to the U.S., which was rapidly building its rail and industrial infrastructure. The growth of pig iron output was dramatic. Britain went from 1.3 million tons in 1840 to 6.7 million in 1870 and 10.4 in 1913.

Technological Advancements

A major change in the metal industries during the era of the Industrial Revolution was the replacement of wood and other bio-fuels with coal. For a given amount of heat, coal required much less labor to mine than cutting wood and converting it to charcoal, and coal was more abundant than wood. Use of coal in smelting started before the Industrial Revolution based on innovations by Sir Clement Clerke and others from 1678, using coal reverberatory furnaces known as cupolas. These were operated by the flames playing on the ore and charcoal or coke mixture, reducing the oxide to metal. This has the advantage that impurities such as sulfur ash in the coal do not migrate into the metal. This technology was applied to lead from 1678 and to copper from 1687. It was also applied to iron foundry work in the 1690s, but in this case the reverberatory furnace was known as an air furnace. The foundry cupola is a different (and later) innovation.

Abraham Darby made great strides using coke to fuel his blast furnaces at Coalbrookdale in 1709. However, the coke pig iron he made was used mostly for the production of cast iron goods, such as pots and kettles. He had the advantage over his rivals in that his pots, cast by his patented process, were thinner and cheaper than theirs. Coke pig iron was hardly used to produce wrought iron in forges until the mid-1750s, when his son Abraham Darby II built Horsehay and Ketley furnaces. By then, coke pig iron was cheaper than charcoal pig iron. Since cast iron was becoming cheaper and more plentiful, it became a structural material following the building of the innovative Iron Bridge in 1778 by Abraham Darby III.

The Iron Bridge crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England, and is the first bridge in the world to be made of cast iron. During the winter of 1773–74, local newspapers advertised a proposal to petition Parliament for leave to construct an iron bridge with a single 120 feet (37 m) span. In 1775, Abraham Darby III, the grandson of Abraham Darby I and an ironmaster working at Coalbrookdale, was appointed treasurer to the project.

Wrought iron for smiths to forge into consumer goods was still made in finery forges, as it long had been. However, new processes were adopted in the ensuing years. The first is referred to today as potting and stamping, but this was superseded by Henry Cort’s puddling process. Cort developed two significant iron manufacturing processes: rolling in 1783 and puddling in 1784. Rolling replaced hammering for consolidating wrought iron and expelling some of the dross. Rolling was 15 times faster than hammering with a trip hammer. Roller mills were first used for making sheets, but also rolled structural shapes such as angles and rails.

Puddling produced structural-grade iron at a relatively low cost. It was a means of decarburizing pig iron by slow oxidation, with iron ore as the oxygen source, as the iron was manually stirred using a long rod. Puddling was done in a reverberatory furnace, allowing coal or coke to be used as fuel. The decarburized iron, having a higher melting point than cast iron, was raked into globs by the puddler. When the glob was large enough, the puddler would remove it. Puddling was backbreaking and extremely hot work. Few puddlers lived to age 40. The process continued ntil the late 19th century when iron was displaced by steel. Because puddling required human skill in sensing the iron globs, it was never successfully mechanized.

Hot blast, patented by James Beaumont Neilson in 1828, was the most important development of the 19th century for saving energy in making pig iron. By using waste exhaust heat to preheat combustion air, the amount of fuel to make a unit of pig iron was reduced at first by between one-third using coal or two-thirds using coke. However, the efficiency gains continued as the technology improved. Hot blast also raised the operating temperature of furnaces, increasing their capacity. Using less coal or coke meant introducing fewer impurities into the pig iron. This meant that lower quality coal or anthracite could be used in areas where coking coal was unavailable or too expensive.

The supply of cheaper iron aided a number of industries, such as those making nails, hinges, wire, and other hardware items. The development of machine tools allowed better working of iron, leading to increased use in the rapidly growing machinery and engine industries. Iron was used in agricultural machines, making farm labor more effective. The new technological advancements were also critical to the development of the rail. Prices of many goods, such as iron cooking utensils, decreased, making them more available and commonly used.

Attribution

- Changes to Iron Production

-

“Industrial Revolution.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“History of the steel industry (1850–1970).” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_steel_industry_(1850%E2%80%931970). Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Reverberatory furnace.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverberatory_furnace. Wikipedis CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Reverberatory_furnace_diagram.png.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reverberatory_furnace_diagram.png. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“The_Iron_Bridge_8542.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Iron_Bridge_(8542).jpg. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0.

-