114 Technological Developments in Textiles

25.2.2: Technological Developments in Textiles

The British textile industry triggered tremendous scientific innovation, resulting in such key inventions as the flying shuttle, spinning jenny, water frame, and spinning mule. These greatly improved productivity and drove further technological advancements that turned textiles into a fully mechanized industry.

Learning Objective

Describe the technology that allowed the textile industry to move towards more automated processes

Key Points

- The exemption of raw cotton from the 1721 Calico Act saw two thousand bales of cotton imported annually from Asia and the Americas, forming the basis of a new indigenous industry. This triggered the development of a series of mechanized spinning and weaving technologies to process the material. This production was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded.

- The textile industry drove groundbreaking scientific innovations. The flying shuttle was patented in 1733 by John Kay. It became widely used around Lancashire after 1760 when John’s son, Robert, designed what became known as the drop box. Lewis Paul patented the roller spinning frame and the flyer-and-bobbin system for drawing wool to an even thickness. The technology was developed with the help of John Wyatt of Birmingham. Paul’s invention was advanced and improved by Richard Arkwright in his water frame and Samuel Crompton in his spinning mule.

- In 1764, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, which he patented in 1770. It was the first practical spinning frame with multiple spindles. The spinning frame or water frame was developed by Richard Arkwright who along with two partners patented it in 1769. The design was partly based on a spinning machine built for Thomas High by clock maker John Kay, who was hired by Arkwright.

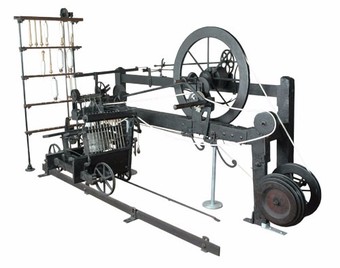

- Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, introduced in 1779, was a combination of the spinning jenny and the water frame. Crompton’s mule spun thread was of suitable strength to be used as warp and finally allowed Britain to produce good-quality calico cloth. Edmund Cartwright developed a vertical power loom that he patented in 1785. Samuel Horrocks and Richard Roberts successively improved Crompton’s invention.

- The textile industry was also to benefit from other developments of the period. In 1765, James Watt modified Thomas Newcomen’s engine (based on Thomas Savery’s earlier invention) to design an external condenser steam engine. Watt continued to make improvements on his design, producing a separate condenser engine in 1774 and a rotating separate condensing engine in 1781. Watt formed a partnership with a businessman Matthew Boulton and together they manufactured steam engines that could be used by industry.

- With Cartwright’s loom, the spinning mule, and Boulton and Watt’s steam engine, the pieces were in place to build a mechanized textile industry. From this point there were no new inventions, but a continuous improvement in technology as the mill-owner strove to reduce cost and improve quality. Steam engines were improved, the problem of line-shafting was addressed by replacing the wooden turning shafts with wrought iron shafting. In addition, the first loom with a cast-iron frame, a semiautomatic power loom, and, finally a self-acting mule were introduced.

Key Terms

- flying shuttle

- One of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. It allowed a single weaver to weave much wider fabrics and could be mechanized, allowing for automatic machine looms. It was patented by John Kay in 1733.

- spinning jenny

- A multi-spindle spinning frame, one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. It was invented in 1764 by James Hargreaves in Stanhill, Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire in England. The device reduced the amount of work needed to produce yarn, with a worker able to make eight or more spools at once.

- water frame

- An machine to create cotton thread first used in 1768. It was able to spin 128 threads at a time, making it an easier and faster method than ever before. It was developed by Richard Arkwright, who patented the technology in 1767. The design was partly based on a spinning machine built for Thomas Highs by clock maker John Kay, who was hired by Arkwright.

- Calico Acts

- Two legislative acts, one of 1700 and one of 1721, that banned the import of most cotton textiles into England, followed by the restriction of sale of most cotton textiles.

- spinning mule

- A machine used to spin cotton and other fibers in the British mills, used extensively from the late 18th to the early 20th century. It was invented between 1775 and 1779 by Samuel Crompton. The machines were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of two boys: the little piecer and the big or side piecer. The carriage carried up to 1,320 spindles and could be 150 feet (46 m) long; it could move forward and back a distance of 5 feet (1.5 m) four times a minute.

Early Developments

During the second half of the 17th century, the newly established factories of the East India Company in South Asia started to produce finished cotton goods in quantity for the UK market. The imported calico and chintz garments competed with and acted as a substitute for indigenous wool and linen produce. That resulted in local weavers, spinners, dyers, shepherds, and farmers petitioning the Parliament to request a ban on the import and later the sale of woven cotton goods. They eventually achieved their goal via the 1700 and 1721 Calico Acts. The acts banned the import and later the sale of finished pure cotton produce, but did not restrict the importation of raw cotton or the sale or production of fustian (a cloth with flax warp and cotton weft).

The exemption of raw cotton from the 1721 Calico Act saw 2,000 bales of cotton imported annually from Asia and the Americas and forming the basis of a new indigenous industry, initially producing fustian for the domestic market. More importantly, though, it triggered the development of a series of mechanized spinning and weaving technologies to process the material. This mechanized production was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded. By the beginning of the 1770s, 7,000 bales of cotton were imported annually. The new mill owners put pressure on Parliament to remove the prohibition on the production and sale of pure cotton cloth as they could now compete with imported cotton.

Since much of the imported cotton came from New England, ports on the west coast of Britain such as Liverpool, Bristol, and Glasgow were crucial to determining the sites of the cotton industry. Lancashire became a center for the nascent cotton industry because the damp climate was better for spinning the yarn. As the cotton thread was not strong enough to use as warp, wool, linen, or fustian had to be used and Lancashire was an existing wool center.

Key Inventions

The textile industry drove groundbreaking scientific innovations. The flying shuttle was patented in 1733 by John Kay and saw a number of subsequent improvements including an important one in 1747 that doubled the output of a weaver It became widely used around Lancashire after 1760 when John’s son, Robert, designed a method for deploying multiple shuttles simultaneously, enabling the use of wefts of more than one color and making it easier for the weaver to produce cross-striped material. These shuttles were housed at the side of the loom in what became known as the drop box. Lewis Paul patented the roller spinning frame and the flyer-and-bobbin system for drawing wool to a more even thickness. The technology was developed with the help of John Wyatt of Birmingham. Paul and Wyatt opened a mill in Birmingham, which used their new rolling machine powered by a donkey. In 1743, a factory opened in Northampton with 50 spindles on each of five of Paul and Wyatt’s machines. It operated until about 1764. A similar mill was built by Daniel Bourn in Leominster, but it burnt down. Both Paul and Bourn patented carding machines in 1748. Based on two sets of rollers that traveled at different speeds, these were later used in the first cotton spinning mill. Lewis’s invention was advanced and improved by Richard Arkwright in his water frame and Samuel Crompton in his spinning mule.

In 1764 in the village of Stanhill, Lancashire, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, which he patented in 1770. It was the first practical spinning frame with multiple spindles. The jenny worked in a similar manner to the spinning wheel by first clamping down on the fibers then drawing them out, followed by twisting. It was a simple, wooden-framed machine that cost only about £6 for a 40-spindle model in 1792 and was used mainly by home spinners. The jenny produced a lightly twisted yarn only suitable for weft, not warp.

The device reduced the amount of work needed to produce yarn, with a worker able to work eight or more spools at once. This grew to 120 as technology advanced.

The spinning frame or water frame was developed by Richard Arkwright who along with two partners patented it in 1769. The design was partly based on a spinning machine built for Thomas High by clock maker John Kay, who was hired by Arkwright. For each spindle, the water frame used a series of four pairs of rollers, each operating at a successively higher rotating speed to draw out the fiber, which was then twisted by the spindle. The roller spacing was slightly longer than the fiber length. Closer spacing caused the fibers to break while further spacing caused uneven thread. The top rollers were leather-covered and loading on them was applied by a weight that kept the twist from backing up before the rollers. The bottom rollers were wood and metal, with fluting along the length. The water frame was able to produce a hard, medium count thread suitable for warp, finally allowing 100% cotton cloth to be made in Britain. A horse powered the first factory to use the spinning frame. Arkwright and his partners used water power at a factory in Cromford, Derbyshire in 1771, giving the invention its name.

Richard Arkwright is credited with a list of inventions, but these were actually developed by such people as Thomas Highs and John Kay. Arkwright nurtured the inventors, patented the ideas, financed the initiatives, and protected the machines. He created the cotton mill, which brought the production processes together in a factory, and he developed the use of power—first horse power and then water power—which made cotton manufacture a mechanized industry.

Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, introduced in 1779, was a combination of the spinning jenny and the water frame. The spindles were placed on a carriage that went through an operational sequence during which the rollers stopped while the carriage moved away from the drawing roller to finish drawing out the fibers as the spindles started rotating. Crompton’s mule was able to produce finer thread than hand spinning at a lower cost. Mule spun thread was of suitable strength to be used as warp and finally allowed Britain to produce good-quality calico cloth.

Realizing that the expiration of the Arkwright patent would greatly increase the supply of spun cotton and lead to a shortage of weavers, Edmund Cartwright developed a vertical power loom which he patented in 1785. Cartwright’s loom design had several flaws, including thread breakage. Samuel Horrocks patented a fairly successful loom in 1813; it was improved by Richard Roberts in 1822, and these were produced in large numbers by Roberts, Hill & Co.

The textile industry was also to benefit from other developments of the period. As early as 1691, Thomas Savery made a vacuum steam engine. His design, which was unsafe, was improved by Thomas Newcomen in 1698. In 1765, James Watt further modified Newcomen’s engine to design an external condenser steam engine. Watt continued to make improvements on his design, producing a separate condenser engine in 1774 and a rotating separate condensing engine in 1781. Watt formed a partnership with a businessman Matthew Boulton and together they manufactured steam engines that could be used by industry.

Mechanization of the Textile Industry

With Cartwright’s loom, the spinning mule, and Boulton and Watt’s steam engine, the pieces were in place to build a mechanized textile industry. From this point there were no new inventions, but a continuous improvement in technology as the mill-owner strove to reduce cost and improve quality. Developments in the transport infrastructure such as the canals and, after 1830, the railways, facilitated the import of raw materials and export of finished cloth.

The use of water power to drive mills was supplemented by steam-driven water pumps and then superseded completely by the steam engines. For example, Samuel Greg joined his uncle’s firm of textile merchants and on taking over the company in 1782, sought out a site to establish a mill. Quarry Bank Mill was built on the River Bollin at Styal in Cheshire. It was initially powered by a water wheel, but installed steam engines in 1810. In 1830, the average power of a mill engine was 48 horsepower (hp), but Quarry Bank mill installed an new 100 hp water wheel. This would change in 1836, when Horrocks & Nuttall, Preston took delivery of 160 hp double engine. William Fairbairn addressed the problem of line-shafting and was responsible for improving the efficiency of the mill. In 1815, he replaced the wooden turning shafts that drove the machines to wrought iron shafting, which were a third of the weight and absorbed less power. The mill operated until 1959.

In 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast-iron frame, the Roberts Loom. In 1842, James Bullough and William Kenworthy made a semiautomatic power loom known as the Lancashire Loom. Although it was self-acting, it had to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century, when the Northrop Loom invented in 1894 with an automatic weft replenishment function gained ascendancy.

The 1824 Stalybridge mule spinners strike stimulated research into the problem of applying power to the winding stroke of the mule. In 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. The draw while spinning had been assisted by power, but the push of the wind was done manually by the spinner. Before 1830, the spinner would operate a partially powered mule with a maximum of 400 spindles. After 1830, self-acting mules with up to 1,300 spindles could be built. The savings with this technology were considerable. A worker spinning cotton at a hand-powered spinning wheel in the 18th century would take more than 50,000 hours to spin 100 pounds of cotton. By the 1790s, the same quantity could be spun in 300 hours by mule, and with a self-acting mule it could be spun by one worker in just 135 hours.

Export Technology

While profiting from expertise arriving from overseas, Britain was very protective of home-grown technology. In particular, engineers with skills in constructing the textile mills and machinery were not permitted to emigrate — particularly to the fledgling America. However, Samuel Slater,an engineer who had worked as an apprentice to Arkwright’s partner Jedediah Strutt, evaded the ban. In 1789, he took his skills in designing and constructing factories to New England and was soon engaged in reproducing the textile mills that helped America with its own industrial revolution. Local inventions followed. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented and patented the cotton gin, which sped up the processing of raw cotton by over 50 times. With a cotton gin a man could remove seed from as much upland cotton in one day as would have previously taken a woman working two months to process at one pound per day.

Attributions

- Technological Developments in Textiles

-

“Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textile_manufacture_during_the_Industrial_Revolution. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Robert Kay (inventor).” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Kay_(inventor). Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Industrial Revolution.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Mule-jenny.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mule-jenny.jpg. Wikimedia Commons GNU FDL 1.2.

-

“Waterframe.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waterframe.jpg. Wikimedia Commons GNU FDL 1.2.

-

“Spinning_jenny.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spinning_jenny.jpg. Wikimedia Commons GNU FDL 1.2.