71 Civil Liberties: How are basic freedoms secured?

Learning Objectives

- Identify the liberties and rights guaranteed by the first four amendments to the Constitution

- Explain why these rights and liberties are limited in actual practice

- Explain why interpreting some amendments has been controversial

The Bill of Rights provisions can broadly divided into three categories. The First, Second, Third, and Fourth Amendments protect basic individual freedoms; the Fourth (partly), Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth protect people suspected or accused of criminal activity; the Ninth and Tenth are consistent with the framers’ view that the Bill of Rights is not necessarily an exhaustive list of all the rights people have and guarantees a role for state as well as federal government.

Individual Freedoms

The First Amendment protects the right to freedom of religious conscience and practice and the right to free expression, particularly of political and social beliefs. The Second Amendment protects the right to bear arms, as well as the collective right to protect the community as part of the militia. The Third Amendment prohibits the government from commandeering people’s homes to house soldiers, particularly in peacetime. Finally, the Fourth Amendment prevents the government from searching our persons or property or taking evidence without a warrant issued by a judge, with certain exceptions.

The First Amendment

The First Amendment is perhaps the most famous provision of the Bill of Rights; it is arguably the most extensive, because it guarantees both religious freedoms and the right to express your views in public. Specifically, the First Amendment says:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Given the broad scope of this amendment, it is helpful to break it into its two major parts.

The first part protects two related aspects of religious freedom: first, it prevents the government from imposing a specific religion on the people, and secondly it prevents the government from restricting the people from recognition and exercise of their own specific religion.

The Establishment Clause

The establishment clause is the first of these. Congress cannot create or promote a state-sponsored religion (this also includes the states now). When the United States was founded, most countries’ governments had an established church or religion, an officially sponsored set of religious beliefs and values. Direct alliances between a state and a religion frequently led to religiously aligned wars and state sponsored tyranny against anyone with religious beliefs outside of the official church.

Many settlers in the United States were refugees from these wars and state sponsored religious intolerance; they sought the freedom to follow their own religion with like-minded people in relative peace. As a practical matter, even if the early United States had tried to establish a single national religion, the existing diversity of religious beliefs would have hindered it.

The establishment clause today is interpreted more broadly; it forbids the creation of a “Church of the United States” or “Church of Ohio” and forbids the government from favoring one set of religious beliefs over others or favoring religion (of any variety) over non-religion.

The key question facing the courts is whether the establishment clause should be understood as imposing, in Thomas Jefferson’s words, “a wall of separation between church and state.” In a 1971 case known as Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Supreme Court established the Lemon test for deciding whether a law or other government action that might promote a particular religious practice should be allowed to stand.[1]

The Lemon test has three criteria that must be satisfied for such a law or action to be found constitutional and remain in effect:

- The action or law must not lead to excessive government entanglement with religion; in other words, policing the boundary between government and religion should be relatively straightforward and not require extensive effort by the government.

- The action or law cannot either inhibit or advance religious practice; it should be neutral in its effects on religion.

- The action or law must have some secular purpose; there must be some non-religious justification for the law.

A school cannot prohibit students from voluntary, non-disruptive prayer because that would impair the free exercise of religion. The general statement that “prayer in schools is illegal” or unconstitutional is incorrect. However, the establishment clause does limit official endorsement of any religion, including prayers organized or otherwise facilitated by school authorities, even as part of off-campus or extracurricular activities.[2]

Some laws appearing to establish certain religious practices are allowed. The courts have permitted religiously inspired blue laws, for example, limiting working hours or even shuttering businesses on Sunday, the Christian day of rest, because by allowing people to practice their (Christian) faith, such rules may help ensure the “health, safety, recreation, and general well-being” of citizens. They have allowed restrictions on the sale of alcohol and sometimes other goods on Sunday for similar reasons.

Why has the establishment clause been so controversial? Government officials acknowledge that we live in a society with vigorous religious practice where most people believe in God—even if we disagree on the nature of God or how to worship. Disputes often arise over how much the government can acknowledge this widespread religious belief. The courts have allowed for a certain tolerance of what is described as ceremonial deism, an acknowledgement of God or a creator that lacking any specific and substantive religious detail. For example, the national motto “In God We Trust,” appearing on our coins and paper money, is seen as more of an acknowledgment that most citizens believe in God than of any effort by government officials to promote religious belief and practice. This reasoning applies to the inclusion of the phrase “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance—a change originating during the early years of the Cold War.

The courts have also allowed some religiously motivated actions by government agencies, such as clergy delivering prayers to open city council meetings and legislative sessions, on the presumption that—unlike school children—adult participants can distinguish between the government’s allowing someone to speak and endorsing that person’s speech. Yet, while some displays of religious codes (e.g., Ten Commandments) are permitted in the context of showing the evolution of law over the centuries, in other cases, these displays have been removed after state supreme court rulings. In Oklahoma, the courts ordered the removal of a Ten Commandments sculpture at the state capitol when other groups, including Satanists and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, attempted to get their own sculptures allowed there on an equal footing.

The Free Exercise Clause

The free exercise clause limits the government’s ability to control or restrict specific group or individual religious practices. It does not regulate the government’s promotion of religion, but rather government suppression of religious beliefs and practices. Controversy surrounding the free exercise clause reflects the way laws or rules that apply to everyone might apply to people with particular religious beliefs. For example, can a Jewish police officer whose religious belief requires her to observe Shabbat be compelled to work on a Friday night or during the day on Saturday? Or must the government accommodate this religious practice even if the general law or rule in question is not applied equally to everyone?

In the 1930s and 1940s, Jehovah’s Witness cases demonstrated the difficulty of striking the right balance. Their church teaches that they should not participate in military combat. It’s members also refuse to participate in displays of patriotism, including saluting the flag and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. They also regularly recruit converts through door-to-door evangelism. These activities have led to frequent conflict with local authorities. Jehovah’s Witness children were punished in public schools for failing to salute the flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and members attempting to evangelize were arrested for violating laws prohibiting door-to-door solicitation. In early legal challenges brought by Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Supreme Court was reluctant to overturn state and local laws that burdened their religious beliefs.[3]

However, in later cases, the court upheld the rights of Jehovah’s Witnesses to proselytize and refuse to salute the flag or recite the Pledge.[4]

The rights of conscientious objectors—individuals who refuse to perform military service on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion—have also been controversial, although many conscientious objectors have contributed service as non-combatant medics during wartime. To avoid serving in the Vietnam War, many people claimed conscientious objection to military service in a war they considered unwise or unjust. The Supreme Court, however, ruled in Gillette v. United States that to claim to be a conscientious objector, a person must be opposed to serving in any war, not just some wars.[5]

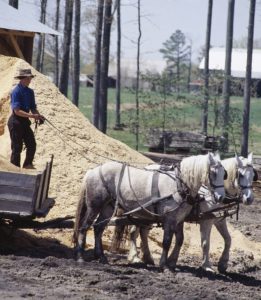

The Supreme Court has been challenged to establish a general framework for deciding if a religious belief can override general laws and policies. In the 1960s and 1970s, the court decided two establishing a general test for deciding similar future cases. In both Sherbert v. Verner, dealing with unemployment compensation, and Wisconsin v. Yoder, dealing with the right of Amish parents to homeschool their children, the court said that for a law to be allowed to limit or burden a religious practice, the government must meet two criteria.[6]

It must demonstrate both a “compelling governmental interest” in limiting that practice and that restriction must be “narrowly tailored.” In other words, it must show a very good reason for that law and demonstrate that the law was the only feasible way of achieving that goal. This standard became known as the Sherbert test. Since the burden of proof in these cases was on the government, the Supreme Court made it very difficult for the federal and state governments to enforce laws against individuals that would infringe upon their religious beliefs.

In 1990, the Supreme Court made a controversial decision substantially narrowing the Sherbert test in Employment Division v. Smith, more popularly known as “the peyote case.”[7]

This case involved two men who were members of the Native American Church, a religious organization that uses the hallucinogenic peyote plant as part of its sacraments. After being arrested for possession of peyote, the two men were fired from their jobs as counselors at a private drug rehabilitation clinic. When they applied for unemployment benefits, the state refused to pay on the basis that they had been dismissed for work-related reasons. The men appealed the denial of benefits and were initially successful, since the state courts applied the Sherbert test and found that the denial of unemployment benefits burdened their religious beliefs. However, the Supreme Court ruled in a 6–3 decision that the “compelling governmental interest” standard should not apply; instead, so long as the law was not designed to target a person’s religious beliefs in particular, it was not up to the courts to decide that those beliefs were more important than the law in question.

On the surface, a case involving the Native American Church seems unlikely to arouse much controversy. It replaced the Sherbert test with one allowing more government regulation of religious practices and followers of other religions grew concerned that state and local laws, even ones neutral on their face, might be used to curtail their own religious practices. Congress responded to this decision in 1993 with a law known as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), followed in 2000 by the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act after part of the RFRA was struck down by the Supreme Court. According to the Department of Justice, RFRA mandates strict scrutiny before government may violate religious freedoms/free exercise of religious beliefs. RLUIPA designates the government may not impose a “substantial burden” on individual exercise of beliefs or religious freedoms and government must use “the least restrictive means” of carrying out policy while furthering “a compelling interest” on the part of the government.[8] Land zoning issues, eminent domain, and the rights of prisoners exercising their religious beliefs drove the perceived need for this legislation. In addition, twenty-one states have passed state RFRAs since 1990 that include the Sherbert test in state law, and state court decisions in eleven states have enshrined the Sherbert test’s compelling governmental interest interpretation of the free exercise clause into state law.[9]

However, the RFRA itself has its critics. While relatively uncontroversial as applied to the rights of individuals, debate has emerged whether businesses and other groups have religious liberty. In explicitly religious organizations, such as a fundamentalist congregations or the Roman Catholic Church, members have a meaningful, shared religious belief. The application of the RFRA has become more problematic in businesses and non-profit organizations whose owners or organizers may share a religious belief while the organization has some secular, non-religious purpose.

Such a conflict emerged in the 2014 Supreme Court case known as Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.[10]

The Hobby Lobby chain sells arts and crafts merchandise at hundreds of stores; its founder David Green is a devout Christian whose beliefs include opposition to abortion. Consistent with these beliefs, he objected to a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) requiring employer-backed insurance plans to include no-charge access to the morning-after pill, a form of emergency contraception, arguing that this requirement infringed on his protected First Amendment right to exercise his religious beliefs. Based in part on the federal RFRA, the Supreme Court agreed 5–4 with Green and Hobby Lobby’s position and said that Hobby Lobby and other closely held businesses did not have to provide employees free access to emergency contraception or other birth control if doing so would violate the religious beliefs of the business’ owners, because there were other less restrictive ways the government could ensure access to these services for Hobby Lobby’s employees (e.g., paying for them directly).

In 2015, state RFRAs became controversial when individuals and businesses providing wedding services (e.g., catering and photography) were compelled to provide services for same-sex weddings in states where the practice had been newly legalized. Proponents of state RFRA laws argued that people and businesses should not be compelled to endorse practices their counter to their religious beliefs and feared clergy might be compelled to officiate same-sex marriages against their religion’s specific teachings. Opponents of RFRA laws argued that individuals and businesses should be required, per Obergefell v. Hodges, to serve same-sex marriages on an equal basis as a matter of ensuring the rights of gays and lesbians.[11]

Despite ongoing controversy the courts have consistently found some public interests sufficiently compelling to override the free exercise clause. For example, since the late nineteenth century the courts have consistently held that people’s religious beliefs do not exempt them from the general laws against polygamy. Other potential acts in the name of religion that are also out of the question are drug use and human sacrifice.

Freedom of Expression

Although the remainder of the First Amendment protects four distinct rights—free speech, press, assembly, and petition—today we view them as encompassing a right to freedom of expression, particularly as technological advances blur the lines between oral and written communication (i.e., speech and press).

Controversies over freedom of expression were rare until the 1900s, even amidst common government censorship. During the Civil War the Union post office refused to deliver newspapers opposing the war or sympathizing with the Confederacy, while allowing distribution of pro-war newspapers. The emergence of photography and movies, in particular, led to new public concerns about morality, causing both state and federal politicians to censor lewd and otherwise improper content. At the same time, writers became emboldened and included explicit references to sex and obscene language, leading to government censorship of books and magazines.

Censorship reached its height during World War I. The United States was swept up in two waves of hysteria. Germany’s actions leading up to United States involvement, including the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and the Zimmerman Telegram (an effort to ally with Mexico against the United States) provoked significant anti-German feelings. Further, the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 overthrowing the Russian government called for communist revolutionaries to overthrow the capitalist, democratic governments in western Europe and North America.

Americans vocally supporting the communist cause or opposing the war often found themselves in jail. In Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that people encouraging young men to dodge the draft could be imprisoned, arguing that recommending people disobey the law was tantamount to “falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic” and thus presented a “clear and present danger” to public order.[12]

Similarly, communists and other revolutionary anarchists and socialists during the post-war Red Scare were prosecuted under various state and federal laws for supporting the forceful or violent overthrow of government. This restriction to political speech continued for the next fifty years.

However, in the 1960s the Supreme Court’s rulings on free expression became more liberal, in response to the Vietnam War and the growing antiwar movement. In a 1969 case involving the Ku Klux Klan, Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court ruled that only speech or writing that constituted a direct call or plan to imminent lawless action, an illegal act in the immediate future, could be suppressed; the mere advocacy of a hypothetical revolution was not enough.[13]

The Supreme Court also ruled that various forms of symbolic speech—wearing clothing like an armband that carried a political symbol or raising a fist in the air, for example—were subject to the same protections as written and spoken communication.

Burning the U.S. Flag

Perhaps no act of symbolic speech has been as controversial in U.S. history as the burning of the flag. Citizens tend to revere the flag as a unifying symbol of the country in much the same way most people in Britain would treat the reigning queen (or king). States and the federal government have long had laws protecting the flag from desecration—defacing, damaging, or otherwise treating it with disrespect. Perhaps in part because of these laws, people wanting to publicize opposition to U.S. government policies have used desecrating the flag a useful way to gain public and press attention to their cause.

Note the case of Gregory Lee Johnson, a member of various pro-communist and antiwar groups. As part of a protest near the Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas in 1984 Johnson set fire to a U.S. flag that another protestor had torn from a flagpole. He was arrested, charged with “desecration of a venerated object” (among other offenses), and eventually convicted. However, in 1989 the Supreme Court decided in Texas v. Johnson that burning the flag was a form of symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment and found the law, as applied to flag desecration, to be unconstitutional.[14]

This court decision was strongly criticized, and Congress responded with a new federal law, the Flag Protection Act, intended to overrule it; this Act was also struck down as unconstitutional in 1990.[15]

Since then, Congress has attempted several times to propose constitutional amendments allowing the states and federal government to re-criminalize flag desecration—to no avail.

Should we amend the Constitution to allow Congress or the states to pass laws protecting the U.S. flag from desecration? Should we protect other symbols as well? Why or why not?

Commercial speech does not retain the same protections as individual free speech and expression. Commercial speech or advertising is subject to more scrutiny by the government because it involves companies or individuals seeking to make a profit.[16] The government protects consumers from business or individuals who would lie to customers in order to make a profit.

Keeping Drug Advertising Honest and Balanced

Each year, drug companies spend about $25 billion in the United States promoting their prescription medications. Most goes to promoting drugs to health care professionals, but a growing amount—about one-fifth—is spent on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising.

Thomas Abrams is the director of the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). He addresses how the FDA protects consumers from false or misleading ads for prescription drugs that appear on TV, radio, online, and in print publications.

Q: The United States and New Zealand are the only countries where prescription drug advertising is directed at consumers. Why is it allowed?

A: The First Amendment provides for freedom of speech, including commercial speech by companies. Direct-to-consumer advertising is considered commercial speech. FDA is charged by law to make sure advertising and other promotional materials are accurate and balanced, and provide helpful information to consumers about medical conditions and drugs to treat them.[17]

Freedom of the press is another important component of the right to free expression. In Near v. Minnesota, a 1931 case regarding press freedoms, the Supreme Court ruled that the government generally could not engage in prior restraint; that is, states and the federal government could not prohibit someone from publishing something in advance without a very compelling reason.[18]

This standard was reinforced in the Pentagon Papers case of 1971, when the Supreme Court ruled that the government could not prohibit the New York Times and Washington Post newspapers from publishing the Pentagon Papers.[19]

These papers included materials from a secret history of the Vietnam War compiled by the military. These papers were compiled at the request of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and provided a study of U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Daniel Ellsberg famously released passages of the Papers to the press to show that the United States had secretly enlarged the scope of the war by bombing Cambodia and Laos while lying to the American public.

Although people who leak secret information to the media can still be prosecuted and punished, this does not generally extend to reporters and news outlets that pass that information on to the public. The Edward Snowden case is a good example. Snowden himself, rather than those involved in promoting the information that he shared, became the object of criminal prosecution.

The courts have further recognized that government officials and other public figures might try to silence press criticism and avoid unfavorable news coverage by threatening a lawsuit for defamation of character. In the 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan case, the Supreme Court decided that public figures must demonstrate not only the falsehood of a negative press statement about them, but also that the statement was conveyed with either malicious intent or “reckless disregard” for the truth.[20]

This ruling made it much harder for politicians to silence potential critics or to bankrupt their political opponents through the courts.

The right to freedom of expression is not absolute; several key restrictions limit our ability to speak or publish opinions under certain circumstances. We have seen that the Constitution protects most forms of offensive and unpopular expression, particularly political speech; however, incitement of a criminal act, “fighting words,” and genuine threats are not protected. So, for example, you cannot point at someone in front of an angry crowd and shout, “Let’s beat up that guy!” And the Supreme Court has allowed laws that ban threatening symbolic speech, such as burning a cross on the lawn of an African American family’s home.[21]

Finally, defamation of character—whether in written form (libel) or spoken form (slander)—is not protected by the First Amendment. People subject to false accusations can sue to recover damages although criminal prosecutions of libel and slander are rare.

Obscenity is another exception to the right to freedom of expression. These are acts or statements considered extremely offensive under the current societal standards. The courts are understandably challenged to define obscenity; Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said of obscenity, having watched pornography in the Supreme Court building, “I know it when I see it.” Into the early twentieth century written works were frequently banned as obscene, including those by noted authors such as James Joyce and Henry Miller. Today it is rare for the courts to uphold obscenity charges for written material alone. In 1973, the Supreme Court established the Miller test for deciding whether something is obscene: “(a) whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”[22]

Applying this standard has often been problematic. The concept of “contemporary community standards” asserts that obscenity can vary geographically; many people in New York or San Francisco might be unconcerned with something that offends people in Memphis or Salt Lake City. The one form of obscenity that has been banned almost without challenge is child pornography, although the courts have found exceptions even here.

The courts have allowed censorship of less-than-obscene content when broadcast over the airwaves, particularly when available for anyone to receive. Generally these restrictions on indecency—a quality of acts or statements that offend societal norms or may be harmful to minors—apply only to radio and television programming broadcast when children might be in the audience. Most cable and satellite channels follow similar standards for commercial reasons.

In the 1990s Congress compelled television broadcasters to implement a television ratings system enforced by a “V-Chip” in televisions and cable boxes, so parents could better control the television programming their children might watch. However, similar efforts to protect children from pornography on the internet have largely been struck down as unconstitutional. This demonstrates that technology has created new avenues for disseminate obscene material. The Children’s Internet Protection Act, however, requires K–12 schools and public libraries receiving Internet access using special E-rate discounts to filter or block access to material deemed harmful to minors.

The courts have also allowed laws forbidding or compelling certain forms of expression by businesses. Examples are laws requiring nutritional information disclosure on food and beverage containers and warning labels on tobacco products. The federal government requires that prices advertised for airline tickets include all taxes and fees. Many states regulate advertising by lawyers. False or misleading statements made in connection with a commercial transaction can be illegal if they constitute fraud.

The courts have also ruled that, although public school officials are government actors, the First Amendment freedom of expression rights of children attending public schools are somewhat limited. In particular, in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court has upheld restrictions on speech that create “substantial interference with school discipline or the rights of others”[23] or is “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.”[24]

For example, the content of school-sponsored activities like school newspapers and speeches delivered by students can be controlled, either for student instruction in proper adult behavior or to deter student conflict.

Free expression includes the right to assemble peaceably and the right to petition government officials. This right even extends to members of groups whose views most people find abhorrent. Examples are American Nazis and the activist Westboro Baptist Church, whose members are known for protesting at the funerals of U.S. soldiers who have died fighting in the war on terror.[25]

The Supreme Court in National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) v. Alabama (1958) considered the rights of organizations of freely assembled persons to keep membership records confidential. As noted in the David M. Rubenstein Gallery of the National Archives, “Throughout the South, officials sought to discredit the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since it threatened white supremacy.

In 1956, Alabama ordered the review of the organization’s documents, including membership lists. The NAACP refused to disclose its members. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court sided with the NAACP and formally recognized a constitutional right to freedom of association. The forced disclosure of membership lists violated NAACP members’ right ‘to pursue their lawful private interests privately and to associate freely with others.’ By recognizing the importance of confidential membership data, especially among unpopular groups, the NAACP v. Alabama decision furthered informational privacy rights.”[26]

Relying on precedent, the court considered arguments in 2006 involving the Boy Scouts of America. In Boy Scouts of America et al. v. Dale (2000), the court examined competing rights–the rights of an openly gay leader in the BSA, James Dale, who was removed from his position as a scoutmaster (discrimination based on sexual orientation in public accommodation) and the rights of the BSA (1st Amendment protected freedom of assembly), where the Court held: Applying New Jersey’s public accommodations law to require the Boy Scouts to readmit Dale violates the Boy Scouts’ First Amendment right of expressive association. Government actions that unconstitutionally burden that right may take many forms, one of which is intrusion into a group’s internal affairs by forcing it to accept a member it does not desire.[27]

Free expression—although a broad right—is subject to certain constraints to balance it against the interests of public order. In particular, the nature, place, and timing of protests—but not their substantive content—are subject to reasonable limits. The courts have ruled that while people may peaceably assemble in a place that is a public forum, not all public property is a public forum. For example, the inside of a government office building or a college classroom—particularly while someone is teaching—is not generally considered a public forum.

Rallies and protests on land that has other dedicated uses such as roads and highways can be limited to groups that have secured a permit in advance, and those organizing large gatherings may be required to give sufficient notice so government authorities can ensure there is enough security available. However, any such regulation must be viewpoint-neutral; the government may not treat one group differently than another because of its opinions or beliefs. For example, the government can’t permit a rally by a group that favors a government policy but forbid opponents from staging a similar rally. Finally, there have been controversial situations in which government agencies have established free-speech zones for protesters during political conventions, presidential visits, and international meetings in areas that are arguably selected to minimize their public audience or to ensure that the subjects of the protests do not have to encounter the protesters.

Since 2011, as part of the White House website, the Obama administration has included a dedicated system, “We the People: Your Voice in our Government,” for people to make petitions that will be reviewed by administration officials.

Since 2011, as part of the White House website, the Obama administration has included a dedicated system, “We the People: Your Voice in our Government,” for people to make petitions that will be reviewed by administration officials.

The Second Amendment

For such a highly charged political issue, the text of the Second Amendment is among the shortest:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The text’s relative simplicity has not spared it from controversy; arguably, the Second Amendment has become controversial because of its text. Does it merely protect the right of the states to organize and arm a “well regulated militia” for civil defense, or is it a protection of a “right of the people” as a whole to individually bear arms?

Before the Civil War, this would have been a nearly meaningless distinction. In most states white males of military age were considered part of the militia, liable to be called for service to put down rebellions or invasions, and the right “to keep and bear Arms” was considered a common-law right inherited from English law predating the federal and state constitutions.

The beginning of selective incorporation after the Civil War fueled debates over the Second Amendment. In the meantime several southern states adopted laws that restricted the carrying and ownership of weapons by former slaves as part of their black codes. Despite acknowledging a common-law individual right to keep and bear arms, in 1876 the Supreme Court declined, in United States v. Cruickshank, to intervene to ensure the states would respect it.[28]

States gradually began to introduce laws to regulate gun ownership. Federal gun control laws were introduced in the 1930s in response to organized crime, and stricter laws regulating most gun commerce stemming from the street protests of the 1960s. Laws requiring background checks for prospective gun buyers were passed in the early 1980s following an assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. During this period, the Supreme Court’s decisions regarding the meaning of the Second Amendment were ambiguous at best. In United States v. Miller, the Supreme Court upheld the 1934 National Firearms Act’s prohibition of sawed-off shotguns, largely because such weapons did not support the goal of promoting a “well regulated militia.”[29]

This ruling was interpreted to support the view that the Second Amendment protected the right of the states to organize a militia, rather than an individual right. Consequently the lower courts ruled most firearm regulations—including some city and state laws virtually outlawing private ownership of firearms—to be constitutional.

In 2008, in a narrow 5–4 decision on District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court ruled that at least some gun control laws did violate the Second Amendment and that this amendment does protect an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, at least in some circumstances—in particular, “for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home.”[30]

Because the District of Columbia is not a state, this decision immediately confirmed the right only to the federal government and territorial governments. Two years later, in McDonald v. Chicago, the Supreme Court overturned the Cruickshank decision (5–4) and again ruled that the right to bear arms was a fundamental right incorporated against the states, meaning that state regulation of firearms might, in some circumstances, be unconstitutional. In 2015, however, the Supreme Court allowed several of San Francisco’s strict gun control laws to remain in place. This suggested that—as in the case of rights protected by the First Amendment—the courts will not treat gun rights as absolute.[31]

The Third Amendment

The Third Amendment says in full:

“No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

Many consider this Constitutional provision obsolete and unimportant. However, it is worthwhile to note its relevance in the context of the time: colonial citizens were routinely required to quarter British soldiers during training maneuvers, redeployments and occupations, even in peacetime and irrespective of their circumstances. They viewed the British laws requiring them to house these soldiers as particularly offensive and disrespectful. So much so that it had been among the grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence.

Today it seems unlikely the federal government would need to house military forces in civilian lodgings against the will of property owners or tenants; however, perhaps in the same way we consider the Second and Fourth amendments, we can think of the Third Amendment as reflecting a broader idea that our homes lie within a “zone of privacy” that government officials should not violate unless absolutely necessary.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment sits at the boundary between general individual freedoms and the rights of those suspected of crimes. It may reflect James Madison’s broader concern to establish an expectation of privacy from government intrusion at home. The Fourth Amendment protects us from overzealous law enforcement by ensuring investigating authorities have good reason to intrude on people’s privacy and property.

The text of the Fourth Amendment is as follows:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The amendment places limits on both searches and seizures: Searches are efforts to locate evidence and contraband. Seizures are the taking of these items by the government for investigations and as evidence in a criminal prosecution (or, in the case of a person, the detention or taking of the person into custody).

It confirms that officials must apply for and receive a search warrant prior to a search or seizure; this warrant is a legal document, signed by a judge, allowing police to search and/or seize persons or property. Since the 1960s, however, the Supreme Court has issued a series of rulings limiting the warrant requirement in situations where a person lacks a “reasonable expectation of privacy” outside the home. Police can also search and/or seize people or property without a warrant if the owner or renter consents to the search, if there is a reasonable expectation that evidence may be destroyed or tampered with before a warrant can be issued (i.e., exigent circumstances), or if the items in question are in plain view of government officials.

Furthermore, the courts have found that police do not generally need a warrant to search the passenger compartment of a car, or to search people entering the United States from another country.[32]

When a warrant is needed, law enforcement officers do not need enough evidence to secure a conviction, but they must demonstrate to a judge that there is probable cause to believe a crime has been committed or evidence will be found. Probable cause is the legal standard for determining whether a search or seizure is constitutional or a crime has been committed; it is a lower threshold than the standard of proof required for a criminal conviction.

What happens when police conduct an illegal search or seizure without a warrant and still find evidence of a crime? In the 1961 Supreme Court case Mapp v. Ohio, the court ruled that evidence obtained without a warrant and not under one of the above exceptions could not be used as evidence in a state criminal trial, leading to the broad application of the exclusionary rule established in 1914 on a federal level in Weeks v. United States.[33]

The exclusionary rule does not just apply to evidence found or to items or people seized without a warrant (or falling under an exception noted above); it also applies to any evidence developed or discovered as a result of the illegal search or seizure.

For example, if police search your home without a warrant, find bank statements showing large cash deposits on a regular basis, and discover evidence of some other unexpected crime (e.g., blackmail, drugs, or prostitution), they cannot use the bank statements as evidence of criminal activity—nor can they prosecute you for other evidence discovered during that illegal search. This extension of the exclusionary rule is sometimes called the “fruit of the poisonous tree,” because just as the metaphorical tree (i.e., the original search or seizure) is poisoned, so is anything that grows out of it.[34]

However, like the requirement for a search warrant, the exclusionary rule does have exceptions. The courts have allowed evidence obtained without the necessary legal procedures in circumstances where police executed warrants they believed were correctly granted but in fact were not (“good faith” exception), and when the evidence would have been found anyway had they followed the law (“inevitable discovery”).

The requirement of probable cause also applies to arrest warrants. A person cannot generally be detained by police or taken into custody without a warrant. However most states allow arrests of a suspected felon without a warrant when probable cause exists, and police can arrest people for minor crimes or misdemeanors they have witnessed themselves.

The first four amendments of the Bill of Rights protect citizens’ key freedoms from governmental intrusion. The First Amendment restricts the government from imposing a specific religion on the people, or limiting the practice of one’s own religion. The First Amendment also protects freedom of expression by the public, the media, and organized groups via rallies, protests, and the petition of grievances. The Second Amendment today protects an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, while the Third Amendment prevents the military occupation of civilians’ homes except under extraordinary circumstances. Finally, the Fourth Amendment protects our persons and property from unreasonable searches and seizures, and protects people from unlawful arrests. However, all these provisions are subject to limitations, often to protect the interests of public order and the good of society as a whole.

Questions to Consider

- Explain the difference between the establishment clause and the free exercise clause, and explain how these two clauses work together to guarantee religious freedoms.

- Explain the difference between the collective rights and individual rights views of the Second Amendment. Which of these views did the Supreme Court’s decision in District of Columbia v. Heller reflect?

Terms to Remember

commercial speech–does not receive the same level of free speech protection because companys or individuals are seeking to make a profit; in order to accomplish this goal, they may not mislead the public or make untrue claims about their product(s)

common-law right–a right of the people rooted in legal tradition and past court rulings, rather than the Constitution

compelling interest–before a right may be curtailed by law the government must provide a compelling interest or very good reason for doing so

establishment clause–the provision of the First Amendment that prohibits the government from endorsing a state-sponsored religion; interpreted as preventing government from favoring some religious beliefs over others or religion over non-religion

exclusionary rule–a requirement, from Supreme Court case Mapp v. Ohio, that evidence obtained as a result of an illegal search or seizure cannot be used to try someone for a crime

free exercise clause–the provision of the First Amendment that prohibits the government from regulating religious beliefs and practices

libel–written defamation of character; written false information with intent to harm another person

prior restraint–a government action that stops someone from doing something before they are able to do it (e.g., forbidding someone to publish a book he or she plans to release)

probable cause–legal standard for determining whether a search or seizure is constitutional or a crime has been committed; a lower threshold than the standard of proof needed at a criminal trial

search warrant–a legal document, signed by a judge, allowing police to search and/or seize persons or property

slander–spoken defamation of character; spoken false information with an intention to harm another individual

symbolic speech–a form of expression that does not use writing or speech but nonetheless communicates an idea (e.g., wearing an article of clothing to show solidarity with a group)

- Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971). ↵

- See, in particular, Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000), which found that the school district’s including a student-led prayer at high school football games was illegal. ↵

- Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586 (1940). ↵

- West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943); Watchtower Society v. Village of Stratton, 536 U.S. 150 (2002). ↵

- Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437 (1971). ↵

- Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972). ↵

- Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990). ↵

- https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg1488.pdf RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESTORATION ACT OF 1993 (P.L. 103-141) at https://www.justice.gov/jmd/religious-freedom-restoration-act-1993-pl-103-141 and CHAPTER 21C--PROTECTION OF RELIGIOUS EXERCISE IN LAND USE AND BY INSTITUTIONALIZED PERSONS at https://www.justice.gov/crt/title-42-public-health-and-welfare ↵

- Juliet Eilperin, "31 states have heightened religious freedom protections," Washington Post, 1 March 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2014/03/01/where-in-the-u-s-are-there-heightened-protections-for-religious-freedom/. Three more states passed state RFRAs in the past year. ↵

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. __ (2014). ↵

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015). ↵

- Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919). ↵

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). ↵

- Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989). ↵

- United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990). ↵

- Food and Drug Administration, "Keeping Drug Advertising Honest and Balanced" at http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm355270.htm ↵

- USA.gov, Food and Drug Administration, "Keeping Drug Advertising Honest and Balanced" at http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm355270.htm ↵

- Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931). ↵

- New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971). ↵

- New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). ↵

- See, for example, Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343 (2003). ↵

- Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). ↵

- Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). ↵

- Hazelwood School District et al. v. Kuhlmeier et al., 484 U.S. 260 (1988). ↵

- National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, 432 U.S. 43 (1977); Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011). ↵

- ASSOCIATIONAL PRIVACY 1958 National Archives, David M. Rubenstein Gallery, Records of Rights at https://search.archives.gov/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&affiliate=national-archives&query=NAACP+v+Alabama and http://recordsofrights.org/events/28/associational-privacy ↵

- Boy Scouts of America et al. v. Dale certiorari to the supreme court of new jersey No. 99–699. Argued April 26, 2000—Decided June 28, 2000 Petitioners are the Boy Scouts of America and its Monmouth Council (collectively, Boy Scouts). The Boy Scouts is a private, not-for-profit organization engaged in instilling its system of values in young people. It asserts that homosexual conduct is inconsistent with those values. Respondent Dale is an adult whose position as assistant scoutmaster of a New Jersey troop was revoked when the Boy Scouts learned that he is an avowed homosexual and gay rights activist. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/boundvolumes/530bv.pdf ↵

- United States v. Cruickshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876). ↵

- United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939). ↵

- District of Columbia et al. v. Heller, 554 US 570 (2008), p. 3. ↵

- Richard Gonzales, "Supreme Court Rejects NRA Challenge to San Francisco Gun Rules," National Public Radio, 8 June 2015. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/06/08/412917394/supreme-court-rejects-nra-challenge-to-s-f-gun-rules (March 4, 2016). ↵

- See, for example, Arizona v. Gant, 556 U.S. 332 (2009). ↵

- Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961); Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). ↵

- Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States, 251 U.S. 385 (1920). ↵