33 Ming Dynasty: Exploration to Isolation

The Ming Dynasty was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644. It was the last ethnic Han-led dynasty in China, supplanting the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty before falling to the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty. The Ming Dynasty ruled over the Empire of the Great Ming (Dà Míng Guó), as China was then known. Although the Ming capital, Beijing, fell in 1644, remnants of the Ming throne and power (now collectively called the Southern Ming) survived until 1662. The Civil Service and a strong centralized government developed during this period. Commerce, trade and also naval exploration flourished with ships possibly reaching the Americas in 1421, before Christopher Columbus set sail. Towards the end of the Ming rule, the first European colony, Macao, was founded (1557).

Ming rule saw the construction of a vast navy, including four-masted ships of 1,500 tons displacement, and a standing army of 1,000,000 troops. Over 100,000 tons of iron per year were produced in North China (roughly 1 kg per inhabitant), and many books were printed using movable type. There were strong feelings amongst the Han ethnic group against the rule by non-Han ethnic groups during the subsequent Qing Dynasty, and the restoration of the Ming dynasty was used as a rallying cry up until the modern era. Towards the end of the dynasty, the Emperors increasingly retired from public life and power devolved to influential officials, and also to their eunuchs.

Strife among the ministers, which the eunuchs used to their advantage, and corruption in the court all contributed to the demise of this long dynasty. Their successors would have to deal with the increased influence of the European powers in China, and the subsequent loss of complete autonomy. The earlier overseas explorations yielded to isolationism, as the idea that all outside of China was barbarian took hold, (known as Sinocentrism). However, a China that ceased to deal with outsiders was badly placed to deal with them, which led to her becoming a theatre for European imperial ambition. While China was never conquered by any other power (except by Japan during World War II) from the sixteenth century on, the European powers gained many concessions and established several colonies which undermined the Emperor’s own power.

Origins of the Ming Dynasty

The Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty ruled before the establishment of the Ming Dynasty. Some historians believe the Mongols’ discrimination against Han Chinese during the Yuan dynasty is the primary cause for the end of that dynasty. The discrimination led to a peasant revolt that pushed the Yuan dynasty back to the Mongolian steppes. However, historians such as Joseph Walker dispute this theory. Other causes include paper currency over-circulation, which caused inflation to go up tenfold during the reign of Yuan Emperor Shundi, along with the flooding of the Yellow Riveras a result of the abandonment of irrigation projects. In Late Yuan times, agriculture was in shambles. When hundreds of thousands of civilians were called upon to work on the Yellow River, war broke out. A number of Han Chinese groups revolted, and eventually the group led by Zhu Yuanzhang, assisted by an ancient and secret intellectual fraternity called the Summer Palace people, established dominance. The rebellion succeeded and the Ming Dynasty was established in Nanjing in 1368. Zhu Yuanzhang took Hongwu as his reign title. The Ming dynasty emperors were members of the Zhu family.

Hongwu kept a powerful army organized on a military system known as the Wei-so system, which was similar to the Fu-ping system of the Tang Dynasty. According to Ming Shih Gao, the political intention of the founder of the Ming Dynasty in establishing the Wei-so system was to maintain a strong army while avoiding bonds between commanding officers and soldiers.

Hongwu supported the creation of self-supporting agricultural communities. Neo-feudal land-tenure developments of Late Song times were expropriated with the establishment of the Ming Dynasty. Great land estates were confiscated by the government, fragmented and rented out; private slavery was forbidden. Consequently, after the death of the Yongle Emperor, independent peasant landholders predominated in Chinese agriculture.

It is notable that Hongwu did not trust Confucians. However, during the next few emperors, the Confucian scholar gentry, marginalized under the Yuan for nearly a century, once again assumed their predominant role in running the empire.

Government

The basic pattern of governmental institutions in China has been the same for two thousand years, but every dynasty installed special offices and bureaus for certain purposes. The Ming administration was also structured in this pattern: the Grand Secretariat neige; before: zhongshusheng) was assisting the emperor, besides are the Six Ministries (Liubu) for Personnel (libu), Revenue (hubu), Rites (libu), War (bingbu), Justice (xingbu), and Public Works (gongbu), under the Department of State Affairs (shangshu sheng). The Censorate (duchayuan; before: yushitai) surveiling the work of imperial officials was also an old institution with a new name. The nominal -and often not employed- heads of government, like since the Han Dynasty, were the Three Dukes (sangong: the Grand Mentor taifu, the Grand Preceptor taishi and the Grand Guardian taibao) and the Three Minor Solitaries (sangu). The first emperor of Ming in his persecution mania abolished the Secretariat, the Censorate and the Chief Military Commission (dudufu) and personally took over the responsibility and administration of the respective ressorts, the Six Ministries, the Five Military Commissions (wu junfu), and the censorate ressorts: a whole administration level was cut out and only partially rebuilt by the following emperors. The Grand Secretariat was reinstalled, but without employing Ground Counsellors (“chancellors”). The ministries, headed by a minister (shangshu) and run by directors (langzhong) stayed under direct control of the emperor until the end of Ming, the Censorate was reinstalled and first staffed with investigating censors (jiancha yushi), later with censors-in-chief (du yushi).

Of special interest during the Ming Dynasty is the vast imperial household that was staffed with thousands of eunuchs, headed by the Directorate of Palace Attendants (neishijian), and divided into different directorates (jian) and Services (ju) that had to administer the staff, the rites, food, documents, stables, seals, gardens, state-owned manufacturies and so on.[1] Famous for its intrigues and acting as the eunuch’s secret service was the so-called Western Depot (xichang).

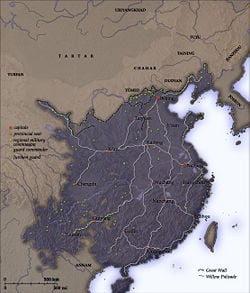

Princes and descendants of the first Ming emperor were given nominal military commands and large land estates, but without title (compare the Han and Jin Dynasties, when princes were installed as kings). The Ming emperors took over the provincial administration system of the Mongols, and the 13 Ming provinces (sheng) are the origin of the modern provinces. On the provincial level, the central government structure was copied, and there existed three provincial commissions: one civil, one military, and one for surveillance. Below province level were the prefectures (fu) under a prefect (zhifu) and subprefectures (zhou) under a subprefect (zhizhou), the lowest unit was the district (xian) under a magistrate (zhixian). Like during the former dynasties, a traveling inspector or Grand Coordinator (xunfu) from the Censorate controlled the work of the provincial administrations. New during the Ming Dynasty was the traveling military inspector (zongdu). Official recruitment was exerted by an examination system that theoretically allowed everyone to link the ranks of imperial officials if he had enough time, money and strength to learn and to write an “eight-legged essay” (baguwen). Passing the provincial examinations, scholars were titled Cultivated Talents (xiuca), passing the metropolitan examination, they obtained the title jinshi “Graduate.”

Exploration to Isolation

This is the only surviving example in the world of a major piece of lacquer furniture from the “Orchard Factory” (the Imperial Lacquer Workshop) set up in Beijing during the early Ming Dynasty. Decorated in dragons and phoenixes it was made to stand in an imperial palace. Made sometime during the Xuande reign period (1426-1435) of the Ming Dynasty. Currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The Chinese gained influence over Turkestan. The maritime Asian nations sent envoys with tributes for the Chinese emperor. Internally, the Grand Canal was expanded to its farthest limits and proved to be a stimulus to domestic trade.

The most extraordinary venture, however, during this stage was the dispatch of Zheng He‘s seven naval expeditions, which traversed the Indian Ocean and the Southeast Asian archipelago. An ambitious eunuch of Hui descent, a quintessential outsider in the establishment of Confucian scholar elites, Zheng He led seven expeditions from 1405 to 1433 with six of them under the auspices of Yongle. He traversed perhaps as far as the Cape of Good Hope and, according to the controversial 1421 theory, to the Americas [2] Zheng’s appointment in 1403 to lead a sea-faring task force was a triumph the commercial lobbies seeking to stimulate conventional trade, not mercantilism.

The interests of the commercial lobbies and those of the religious lobbies were also linked. Both were offensive to the neo-Confucian sensibilities of the scholarly elite: Religious lobbies encouraged commercialism and exploration, which benefited commercial interests, in order to divert state funds from the anti-clerical efforts of the Confucian scholar gentry. The first expedition in 1405 consisted of 317 ships and 28,000 men—then the largest naval expedition in history. Zheng He’s multi-decked ships carried up to 500 troops but also cargoes of export goods, mainly silks and porcelains, and brought back foreign luxuries such as spices and tropical woods.

This tripod planter from the Ming Dynasty is an example of Longquan celadon. It is housed in the Smithsonian in Washington, DC

The economic motive for these huge ventures may have been important, and many of the ships had large private cabins for merchants. But the chief aim was probably political; to enroll further states as tributaries and mark the dominance of the Chinese Empire. The political character of Zheng He’s voyages indicates the primacy of the political elites. Despite their formidable and unprecedented strength, Zheng He’s voyages, unlike European voyages of exploration later in the fifteenth century, were not intended to extend Chinese sovereignty overseas. Indicative of the competition among elites, these excursions had also become politically controversial. Zheng He’s voyages had been supported by his fellow-eunuchs at court and strongly opposed by the Confucian scholar officials. Their antagonism was, in fact, so great that they tried to suppress any mention of the naval expeditions in the official imperial record. A compromise interpretation realizes that the Mongol raids tilted the balance in the favor of the Confucian elites.

By the end of the fifteenth century, imperial subjects were forbidden from either building oceangoing ships or leaving the country. Some historians speculate that this measure was taken in response to piracy. But during the mid-1500s, trade started up again when silver replaced paper money as currency. The value of silver skyrocketed relative to the rest of the world, and both trade and inflation increased as China began to import silver.

Historians of the 1960s, such as John Fairbank III and Joseph Levinson have argued that this renovation turned into stagnation, and that science and philosophy were caught in a tight net of traditions smothering any attempt at something new. Historians who held to this view argue that in the fifteenth century, by imperial decree the great navy was decommissioned; construction of seagoing ships was forbidden; the iron industry gradually declined.

Ming Military Conquests

The beginning of the Ming Dynasty was marked by Ming Dynasty military conquests as they sought to cement their hold on power.

Early in his reign the first Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang provided instructions as injunctions to later generations. These instructions included the advice that those countries to the north were dangerous and posed a threat to the Ming polity and those to the south did not. Furthermore, he stated that those to the south, not constituting a threat, were not to be subject to attack. Yet, either because of or despite this, it was the polities to the south which were to suffer the greatest effects of Ming expansion over the following century. This prolonged entanglement in the south with no long-lasting tangible benefits ultimately weakened the Ming Dynasty.

Agricultural Revolution

Historians consider the Hongwu emperor to be a cruel but able ruler. From the start of his rule, he took great care to distribute land to small farmers. It seems to have been his policy to favor the poor, whom he tried to help to support themselves and their families. For instance, in 1370 an order was given that some land in Hunan and Anhui should be distributed to young farmers who had reached manhood. To preclude the confiscation or purchase of this land by unscrupulous landlords, it was announced that the title to the land was not transferable. At approximately the middle of Hongwu’s reign, an edict was published declaring that those who cultivated wasteland could keep it as their property and would never be taxed. The response of the people was enthusiastic. In 1393, the cultivated land rose to 8,804,623 ching and 68 mou, a record which no other dynasty has reached.

One of the most important aspects of the development of farming was water conservancy. The Hong Wu emperor paid special attention to the irrigation of farms all over the empire, and in 1394 a number of students from Kuo-tzu-chien were sent to all of the provinces to help develop irrigation systems. It is recorded that 40,987 ponds and dikes were dug.

Having himself come from a peasant family, Hong Wu emperor knew very well how much farmers suffered under the gentry and the wealthy. Many of the latter, using influence with magistrates, not only encroached on the land of farmers, but also by bribed sub-officials to transfer the burden of taxation to the small farmers they had wronged. To prevent such abuses the Hongwu Emperor instituted two very important systems: “Yellow Records” and “Fish Scale Records,” which served to guarantee both the government’s income from land taxes and the people’s enjoyment of their property.

Hongwu kept a powerful army organized on a military system known as the wei-so system. The wei-so system in the early Ming period was a great success because of the tun-tien system. At one time the soldiers numbered over a million and Hong Wu emperor, well aware of the difficulties of supplying such a number of men, adopted this method of military settlements. In time of peace each soldier was given forty to fifty mou of land. Those who could afford it supplied their own equipment; otherwise it was supplied by the government. Thus the empire was assured strong forces without burdening the people for its support. The Ming Shih states that 70 percent of the soldiers stationed along the borders took up farming, while the rest were employed as guards. In the interior of the country, only 20 percent were needed to guard the cities and the remaining occupied themselves with farming. So, one million soldiers of the Ming army were able to produces five million piculs of grain, which not only supported great numbers of troops but also paid the salaries of the officers.

Commerce Revolution

Hong Wu’s prejudice against the merchant class did not diminish the numbers of traders. On the contrary, commerce was on much greater scale than in previous centuries and continued to increase, as the growing industries needed the cooperation of the merchants. Poor soil in some provinces and over-population were key forces that led many to enter the trade markets. A book called “Tu pien hsin shu” gives a detailed description about the activities of merchants at that time. In the end, the Hong Wu policy of banning trade only acted to hinder the government from taxing private traders. Hong Wu did continue to conduct limited trade with merchants for necessities such as salts. For example, the government entered into contracts with the merchants for the transport of grain to the borders. In payments, the government issued salt tickets to the merchants, who could then sell them to the people. These deals were highly profitable for the merchants.

Private trade continued in secret because the coast was impossible to patrol and police adequately, and because local officials and scholar-gentry families in the coastal provinces actually colluded with merchants to build ships and trade. The smuggling was mainly with Japan and Southeast Asia, and it picked up after silver lodes were discovered in Japan in the early 1500s. Since silver was the main form of money in China, lots of people were willing to take the risk of sailing to Japan or Southeast Asia to sell products for Japanese silver, or to invite Japanese traders to come to the Chinese coast and trade in secret ports. The Ming court’s attempt to stop this ‘piracy‘ was the source of the wokou wars of the 1550s and 1560s. After private trade with Southeast Asia was legalized again in 1567, there was no more black market. Trade with Japan was still banned, but merchants could simply get Japanese silver in Southeast Asia. Also, Spanish Peruvian silver was entering the market in huge quantities, and there was no restriction on trading for it in Manila. The widespread introduction of silver into China helped monetize the economy (replacing barter with currency), further facilitating trade.

The Ming Code

The legal code drawn up in the time of Hong Wu emperor was considered one of the great achievements of the era. The Ming shih mentions that early as 1364, the monarch had started to draft a code of laws known as Ta-Ming Lu. Hong Wu emperor took great care over the whole project and in his instruction to the ministers told them that the code of laws should be comprehensive and intelligible, so as not to leave any loophole for sub-officials to misinterpret the law by playing on the words. The code of Ming Dynasty was a great improvement on that of Tang Dynasty as regards to treatment of slaves. Under the Tang code slaves were treated almost like domestic animals. If they were killed by a free citizen, the law imposed no sanction on the killer. Under the Ming Dynasty, however, this was not so. The law assumed the protection of slaves as well as free citizens, an ideal that harkens back to the reign of Han Dynasty emperor Guangwu in the first century C.E. The Ming code also laid great emphasis on family relations. Ta-Ming Lu was based on Confucian ideas and remained one of the factors dominating the law of China until the end of the nineteenth century.

Scrapping The Prime Minister Post

Many argue that Hongwu emperor, wishing to concentrate absolute authority in his own hands, abolished the office of prime minister and so removed the only insurance against incompetent emperors. However the statement is misleading as a new post was created called “Senior Grand secretary” which replaced the abolished prime minister post. Ray Huang, Professor from State University College at New Paltz, New York, has argued that Grand-secretaries, outwardly powerless, could exercise considerable positive influence from behind the throne. Because of their prestige and the public trust which they enjoyed, they could act as intermediaries between emperor and the ministerial officials and thus provide stabilizing force in the court.

Decline of the Ming

The Yongle Emperor, as a warrior, was able to maintain the foreign policy of his father. However, Yongle’s successors attached little importance to foreign affairs and this lead to deterioration of the army. Annam regained its independence in 1427 and in the north the Mongols quickly regained their strength. Starting around 1445, the Oirat Horde became a military threat under their new leader Esen Taiji. The Zhengtong Emperor personally led a punitive campaign against the Horde but the mission turned into a disaster as the Chinese army was annihilated and the Emperor was captured. Later, under Jia-Jing Emperor, the capital itself nearly fell into the hands of the Mongols, if not for the heroic efforts of the patriot Yu Qian. At the same time the Wokou Japanese pirates were raging along the coast – a front so extensive that it was scarcely within the power of the government to guard it. It was not until local militiary were formed under Qi Jiguang that the Japanese raids ended. Next, the Japanese under the leadership of Hideyoshi set out to conquer Korea and China through two campaigns known collectively as the Imjin War. While the Chinese defeated the Japanese, the empire suffered financially. By the 1610s, the Ming Dynasty had lost de facto control over northeast China. A tribe descended from Jin dynasty rapidly extended its power as far south as Shanhai Pass, i.e. directly opposite the Great Wall, and would have taken over China quickly if not for the brilliant Ming commander, Yuan Chonghuan. Indeed, the Ming did produce capable commanders such as Yuan Chonghuan, Qi Jiguang, and others; who were able to turn this unfavorable sitation into a satisfactory one. The corruption within the court—largely the fault of the eunuchs—also contributed to the decline of the Ming Dynasty.

The decline of Ming Empire become more obvious in the second half of the Ming period. Most of the Ming Emperors lived in retirement and power often fell into the hands of influential officials, and also sometimes into the hands of eunuchs. Furthering the decline was strife among the ministers, which the eunuchs used to their advantage. Corruption in the court persisted to the end of the dynasty.

Historians debate the relatively slower “progression” of European-style mercantilism and industrialization in China since the Ming. This question is particularly poignant, considering the parallels between the commercialization of the Ming economy, the so-called age of “incipient capitalism” in China, and the rise of commercial capitalism in the West. Historians have thus been trying to understand why China did not “progress” in the manner of Europe during the last century of the Ming Dynasty. In the early twenty-first century, however, some of the premises of the debate have come under attack. Economic historians such as Kenneth Pomeranz have argue that China was technologically and economically equal to Europe until the 1750s and that the divergence was due to global conditions such as access to natural resources from the new world.

Much of the debate nonetheless centers on contrast in political and economic systems between East and West. Given the causal premise that economic transformations induce social changes, which in turn have political consequences, one can understand why the rise of mercantilism, an economic system in which wealth was considered finite and nations were set to compete for this wealth with the assistance of imperial governments, was a driving force behind the rise of modern Europe in the 1600s-1700s. Capitalism after all can be traced to several distinct stages in Western history. Commercial capitalism was the first stage, and was associated with historical trends evident in Ming China, such as geographical discoveries, colonization, scientific innovation, and the increase in overseas trade. But in Europe, governments often protected and encouraged the burgeoning capitalist class, predominantly consisting of merchants, through governmental controls, subsidies, and monopolies, such as British East India Company. The absolutist states of the era often saw the growing potential to excise bourgeois profits to support their expanding, centralizing nation-states.

This question is even more of an anomaly considering that during the last century of the Ming Dynasty a genuine money economy emerged along with relatively large-scale mercantile and industrial enterprises under private as well as state ownership, such as the great textile centers of the southeast. In some respects, this question is at the center of debates pertaining to the relative decline of China in comparison with the modern West at least until the Communist revolution. Chinese Marxist historians, especially during the 1970s identified the Ming age one of “incipient capitalism,” a description that seems quite reasonable, but one that does not quite explain the official downgrading of trade and increased state regulation of commerce during the Ming era. Marxian historians thus postulate that European-style mercantilism and industrialization might have evolved had it not been for the Manchu conquest and expanding European imperialism, especially after the Opium Wars.

Post-modernist scholarship on China, however argues that this view is simplistic and, at worst, wrong. The ban on ocean-going ships, it is pointed out, was intended to curb piracy and was lifted in the Mid-Ming at the strong urging of the bureaucracy who pointed out the harmful effects it was having on coastal economies. These historians, who include Kenneth Pomeranz, and Joanna Waley-Cohen deny that China “turned inward” at all and point out that this view of the Ming Dynasty is inconsistent with the growing volume of trade and commerce that was occurring between China and southeast Asia. When the Portuguese reached India, they found a booming trade network which they then followed to China. In the sixteenth century Europeans started to appear on the eastern shores and the Portuguese founded Macao, the first European settlement in China. As mentioned, since the era of Hongwu the emperor’s role this became even more autocratic, although Hongwu necessarily continued to use what he called the Grand Secretaries to assist with the immense paperwork of the bureaucracy, which included memorials (petitions and recommendations to the throne), imperial edicts in reply, reports of various kinds, and tax records.

Hongwu, unlike his successors, noted the destructive role of court eunuchs under the Song Dynasty, drastically reducing their numbers, forbidding them to handle documents, insisting that they remained illiterate, and liquidating those who commented on state affairs. Despite Hongwu’s strong aversion to the eunuchs, encapsulated by a tablet in his palace stipulating: “Eunuchs must have nothing to do with the administration,” his successors revived their informal role in the governing process. Like its predecessor the Eastern Han Dynasty, the eunuchs would be remembered as the major factor that brings the dynasty to its knees.

Yongle was also very active and very competent as an administrator, but an array of bad precedents was established. First, although Hongwu maintained some Mongol practices, such as corporal punishment, to the consternation of the scholar elite and their insistence on rule by virtue, Yongle exceeded these bounds, executing the families of his political opponents, and murdering thousands arbitrarily. Third, Yongle’s cabinet, or Grand Secretariat, would become a sort of rigidifying instrument of consolidation that became an instrument of decline. Earlier, however, more competent emperors supervised or approved all the decisions of the latter council. Hongwu himself was generally regarded as a strong emperor who ushered in an energy of imperial power and effectiveness that lasted far beyond his reign, but the centralization of authority would prove detrimental under less competent rulers.

Building the Great Wall

After the Ming army defeat at Battle of Tumu and later raids by the Mongols under a new leader, Altan Khan, the Ming adopted a new strategy for dealing with the northern horsemen: a giant impregnable wall, inspired by walls built during the Warring States Period by the states Yan, Zhao, and Qin and linked by Qin.

Almost 100 years earlier (1368) the Ming had started building a new, technically advanced fortification which today is called the Great Wall of China. Created at great expense the wall followed the new borders of the Ming Empire. Acknowledging the control which the Mongols established in the Ordos, south of the Huang He, the wall follows what is now the northern border of Shanxi and Shaanxi provinces. Work on the wall largely superseded military expeditions against the Mongols for the last 80 years of the Ming dynasty and continued up until 1644, when the dynasty collapsed.

The Network of Secret Agents

In the Ming Dynasty, networks of secret agents flourished throughout the military. Due to the humble background of Zhu Yuanzhang before he became emperor, he harbored a special hatred against corrupt officials and had great awareness of revolts. He created the Jinyi Wei, to offer himself further protection and act as secret police throughout the empire. Although there are a few successes in their history, they were more known for their brutality in handling crime than as an actually successful police force. In fact, many of the people they caught were actually innocent. The Jinyi Wei had spread a terror throughout their empire, but their powers were decimated as the eunuchs’ influence at the court increased. The eunuchs created three groups of secret agents in their favor; the East Factory, the West Factory and the Inner Factory. All were no less brutal than the Jinyi Wei and probably worse, since they were more of a tool for the eunuchs to eradicate their political opponents than anything else.

Fall of the Ming Dynasty

The fall of the Ming Dynasty was a protracted affair, its roots beginning as early as 1600 with the emergence of the Manchu under Nurhaci. Under the brilliant commander, Yuan Chonghuan, the Ming were able to repeatedly fight off the Manchus, notably in 1626 at Ning-yuan and in 1628. Succeeding generals, however, proved unable to eliminate the Manchu threat. Earlier, however, in Yuan’s command he had securely fortified the Shanhai pass, thus blocking the Manchus from crossing the pass to attack Liaodong Peninsula.

Unable to attack the heart of Ming directly, the Manchu instead bided their time, developing their own artillery and gathering allies. They were able to enlist Ming government officials and generals as their strategic advisors. A large part of the Ming Army home mutinied to the Manchu banner. In 1633 they completed a conquest of Inner Mongolia, resulting in a large scale recruitment of Mongol troops under the Manchu banner and the securing of an additional route into the Ming heartland.

By 1636 the Manchu ruler Huang Taiji was confident enough to proclaim the Imperial Qing Dynasty at Shenyang, which had fallen to the Manchu in 1621, taking the Imperial title Chongde. The end of 1637 saw the defeat and conquest of Ming’s traditional ally Korea by a 100,000 strong Manchu army, and the Korean renunciation of the Ming Dynasty.

On May 26, 1644, Beijing fell to a rebel army led by Li Zicheng. Seizing their chance, the Manchus crossed the Great Wall after Ming border general Wu Sangui opened the gates at Shanhai Pass, and quickly overthrew Li’s short-lived Shun Dynasty. Despite the loss of Beijing (whose weakness as an Imperial capital had been foreseen by Zhu Yuanzhang) and the death of the Emperor, Ming power was by no means destroyed. Nanjing, Fujian, Guangdong, Shanxi and Yunnan could all have been, and were in fact, strongholds of Ming resistance. However, the loss of central authority saw multiple pretenders for the Ming throne, unable to work together. Each bastion of resistance was individually defeated by the Qing until 1662, when the last real hopes of a Ming revival died with the Yongli emperor, Zhu Youlang. Despite the Ming defeat, smaller loyalist movements continued till the proclamation of the Republic of China.

| Preceded by: Yuan Dynasty |

Ming Dynasty 1368–1644 |

Succeeded by: Qing Dynasty |

Notes

- ↑ Eunuchs were recruited as personal servants of the Emperor from the start of the Ming Dynasty. Eventually, they occupied many significant posts. Tsai (1996) penetrates behind the usual representation of the eunuchs to show how behind the condemnation and jealousy that clouds their role, many served faithfully although many were also corrupt

- ↑ Gavin Menzies, 2004. 1421: the Year China discovered America, the 1421 website, 1421: The Year China Discovered Americapublished evidence that Zheng He sailed to the Americas, while “Will the Real Gavin Menzies Please Stand Up?” by Captain P.J. Rivers seeks to disprove the thesis, Will the Real Gavin Menzies Please Stand Up? Retrieved September 4, 2015.