90 Reading: Art in Nazi Germany

Nazi Art Policy

How do you destroy an artwork? You can hide it, scratch it, tear it, put a slogan over it, burn it, or, as the Nazis did in 1937, simply show it to millions of people.

If you visited Munich in the summer of that year, you could see two spectacular exhibitions that were held only a few hundred meters apart. One was the Great German Art Exhibition, showcasing recent leading examples of ‘Aryan’ art. The other was the Degenerate Art Exhibition, which offered a tour through the art that the National Socialist Party had rejected on ideological grounds. It was made up of art that was not considered ‘Aryan’ and offered a last glimpse before these works of art disappeared.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition cleverly manipulated visitors to loathe and ridicule the art on exhibit, in part by erasing their original meaning. Until shortly before the exhibition, these paintings and sculptures had been displayed at the nation’s greatest museums, but now they were the principal performers in a freak show. The shock-value was enhanced by only allowing over-18s into the exhibition. The lines for the Degenerate Art Exhibition went around the block. Inside, many pictures had been taken out of their frames, and were attached to walls that were emblazoned with outraged slogans. Rather than whispering respectfully, people pointed and snickered. The paintings and sculptures had lost their status as artworks, and were now reduced to dangerous and outrageous rubbish.

Visual symbolism was important to the Nazis, and Hitler himself had been a painter, so it is not surprising that they dedicated significant resources promoting their ideals through art. So how was the decision made? How were ‘degenerate’ and ‘Aryan’ artworks selected? If you look at the works of art that were glorified and compare them to those that were attacked by the Nazis, the differences usually seem clear enough; experimental, personal, non-representational art was rejected, whilst conventionally ‘beautiful,’ stereotypically heroic art was revered. This seems like an obvious line to be taken by a totalitarian regime: everyone will find these artworks beautiful, and everyone will feel and think the same thing about them, without the risk of unwanted, random, personal, or unclear interpretations.

A Very Simple Decision

And the Nazis presented it as a very simple decision, any true German would immediately be able to tell the difference. But in reality, a four-year battle was fought all the way to the top echelons of the Nazi hierarchy over what ‘Aryan’ art was supposed to be, exactly. The opinions on this could not have been more contradictory, and top Nazi officials such as Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg championed the art they each preferred.

Surprisingly, before 1937, Goebbels–and many other Nazis–collected modern art. Goebbels had works of modern art in his study, his living room and was a fan of many artists that eventually ended up in the Degenerate Art Exhibition. Heinrich Himmler was interested in mystical, Germanic art that harked back to a tribal past. Another influential Nazi, Alfred Rosenberg, liked the pastoral, romantic style that depicted humble farmers, rural landscapes and blond maidens.

Hitler would have none of it. He loathed Expressionism and modern art whilst pastoral idylls were not serious enough. Goebbels reversed himself and became one of the driving forces behind the Degenerate Art Exhibition, prosecuting the same artworks he had once enjoyed. Rosenberg also let go, albeit reluctantly, whilst Himmler changed tack and stole artworks by the wagonload behind Hitler’s back throughout the war.

So How Was “Aryan” Art Defined?

In a sense, the concept of “Aryan” art was defined by what it was not: anything that was ideologically problematic (that did not fit with the extremist beliefs of the regime) was removed until there little left but an academic style that celebrated youth, optimism, power and eternal triumph. Nevertheless, it remained difficult for even the most influential Nazis to understand the selection criteria for art sanctioned by the state.

Take for example Adolf Ziegler, who had been in charge of selecting the artwork to be exhibited in the Great German Art Exhibition. Just before the show opened, Hitler visited in order to inspect the artwork chosen to represent the eternal future of Nazi Germany. He was not pleased with the selection his most loyal followers had made. On the 5th of June, 1937, Goebbels wrote in his diary that the Führer was “wild with rage” and subsequently issued a statement declaring “I will not tolerate unfinished paintings,” meaning that the exhibition had to be reconceived at the last minute.

Even opportunistic “hard-liners” like Adolf Ziegler, an artist favored by Hitler, were not quite able to fulfill their patron’s vision. However, it would not be right to conclude that the criteria for art that represented the ‘Aryan’ state appears to have been based principally on the eye of Adolf Hitler rather than a set of delineated characteristics. Even Hitler’s taste was not the ultimate indicator of ‘Aryan’ art: whilst planning what great artworks he would take from the conquered museums of Europe for his never-realized Führer-Museum, he was convinced by his newly appointed museum director that his taste was not up to standard for the world-class museum he envisaged. Rather than firing the man, Hitler deferred to this Dr. Hans Posse, despite the fact that he had recently been fired from his post as museum director in Dresden for endorsing “degenerate art.”

What Was Actually on Display in the Two Exhibitions?

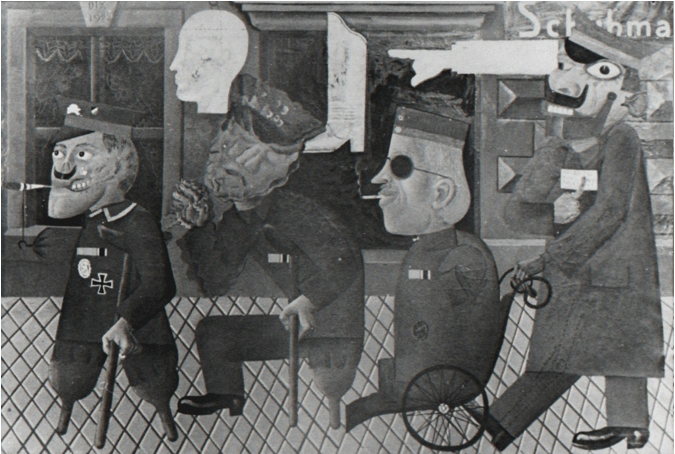

The Degenerate Art Exhibition mostly exhibited Expressionism, New Objectivism and some abstract art. Strangely, very few works came from Jewish artists, and a lot of artworks had until recently been favorites of many Nazis. Renowned works by artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff and Ernst Barlach now hung on walls marked with graffiti. The works ranged from quiet and traditional looking, such as Ernst Barlach’s The Reunion (Das Wiedersehen), 1926 which showed two poised, realistically carved wooden figures holding each other, to more grotesquely painted works, such as Otto Dix’ War Cripples (Kriegskrüppel), 1920. This work shows a procession of cartoonesque yet morbid war veterans, painfully moving forward with the aid of pushchairs, prosthetic legs and crutches, smoking cheerfully, though one soldier’s face is half eaten away, revealing a rictus grin of clenched teeth.

In contrast, the Great German Art Exhibition showed art with the hallmarks of classical tradition, large sculptures of tall and muscular bodies and paintings of heroic soldiers by artists such as Josef Thorak and Arno Breker. Prominent position was given to Breker’s Decathlete (‘Zehnkämpfer’) and Victory (‘Siegerin’), both made in 1936, showing two bronze figures over three metres high, their impersonal facial expressions and perfectly proportioned bodies almost archetypical examples of the classical style.

However, in later editions of the Great German Art Exhibition, works that did not fit the ideals of beauty, youth and optimism crept back in. Realistically painted works depicting soldiers despairing in the trenches by Albert Heinrich and sad, emaciated figures like the bust Der Walzmeister by Fritz Koelle began to share the space with oversized muscular bronze men and paintings of serene nude women.

The random nature of Nazi art policy continued after these exhibitions closed. Breker and Thorak, superstars of the Nazi regime, actually had some works branded as degenerate (though this was quickly covered up), whereas the artist Emil Nolde, who joined the Nazi party and was an early and enthusiastic supporter, had been issued a so-called Malverbot forbidding him to paint even in the privacy of his own home. He received regular visits from the Gestapo, the secret police, who came to touch his brushes to ensure that they had not been used. Nolde became a water-color painter. The brushes dried a lot faster than with oil paint.